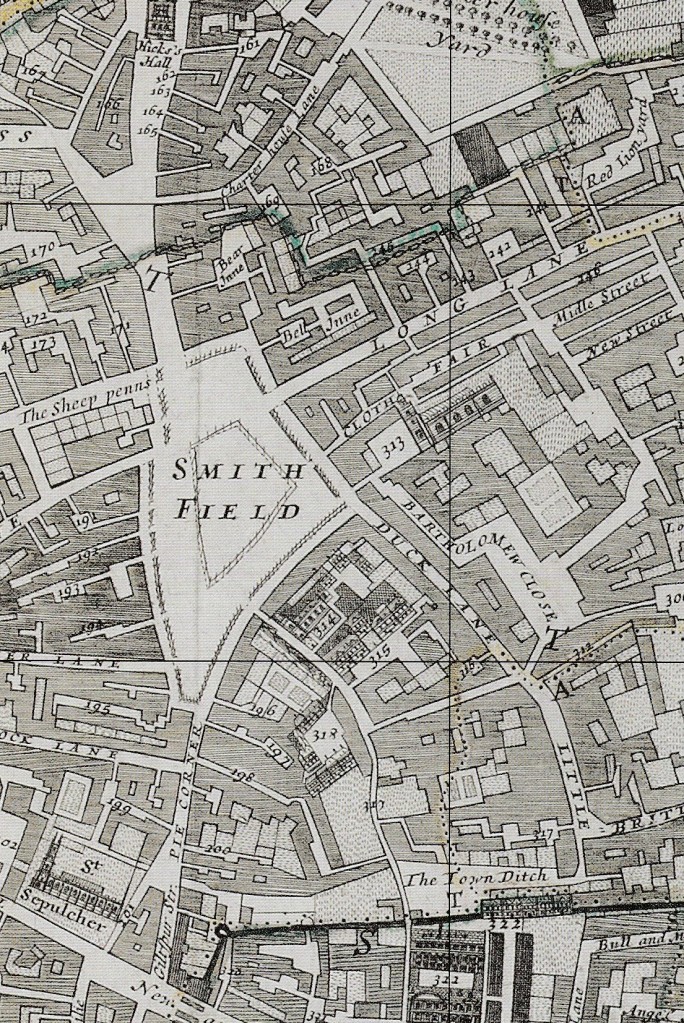

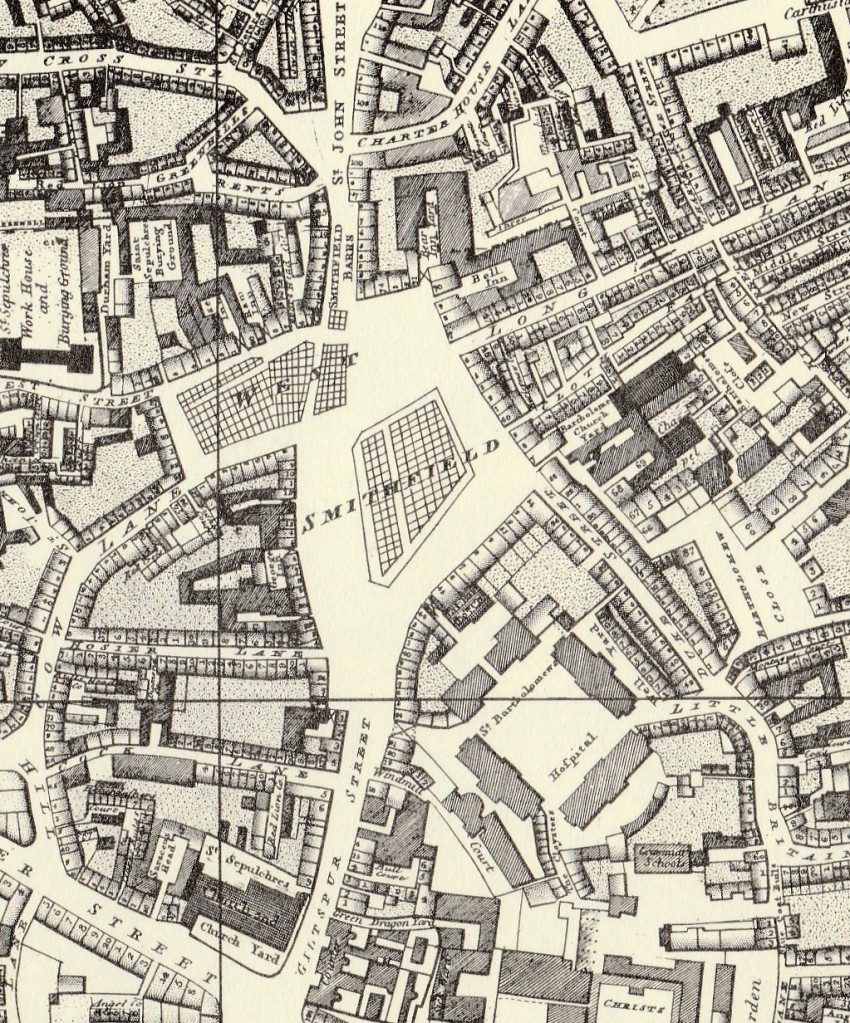

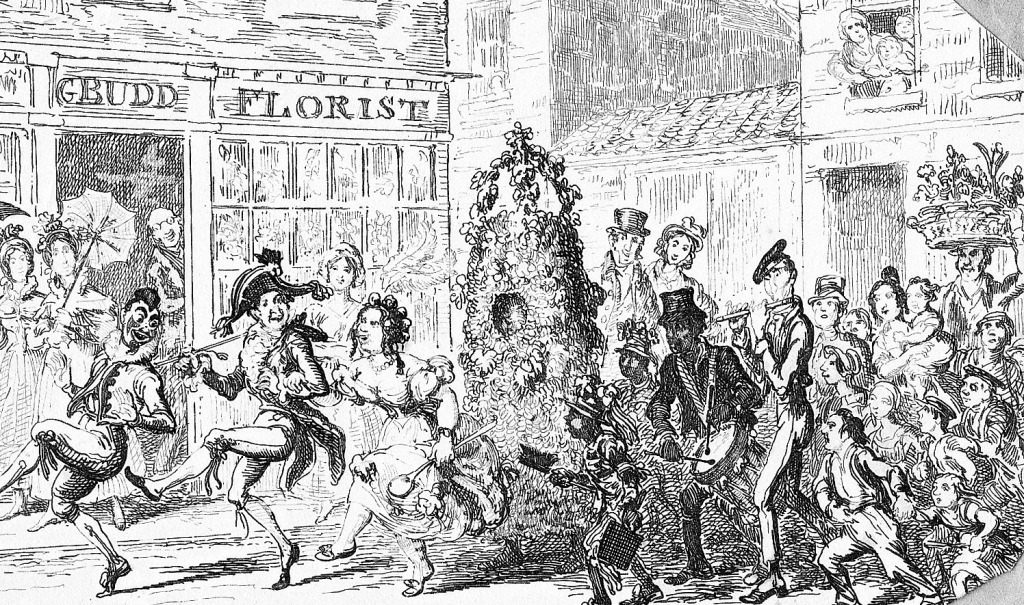

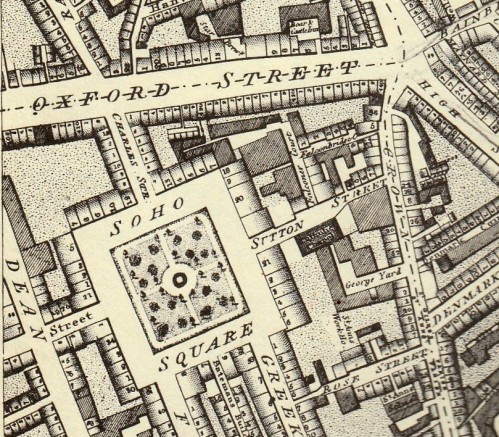

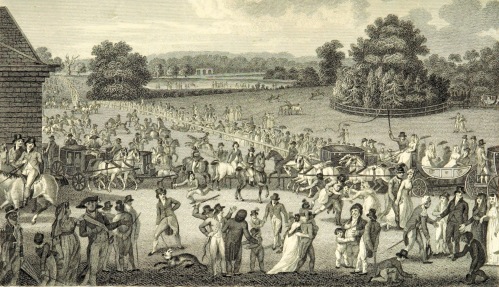

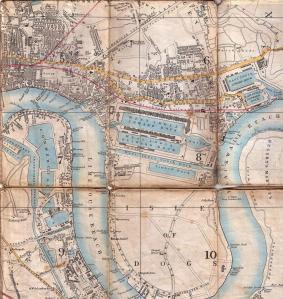

I am keeping my fingers crossed that I will be able to stay in one of the Landmark Trust’s properties in Cloth Fair, Smithfield, this summer. You can see Cloth Fair running off from the north-east side of Smithfield, just below Long Lane, in this map of 1682. The little street gets it name from Bartholomew Fair, founded by royal charter in 1133 for the benefit of the adjacent St Bartholomew’s Hospital. It became the greatest cloth fair in England and the Corporation of London held a cattle fair at the same time. Eventually it became one of the highlights of London life, running for three days in August and, by the 17th century, an entertainment, rather than a market. I wrote about it here in all its rowdy glory. By 1855 it was finally suppressed and Smithfield Market was built in the area at the top of Smithfield, covering the sheep pens and the open space to the east of them that you can see in the 1682 map.

Smithfield was originally the Smooth Field, an area for grazing horses outside the City walls. – you can see the Town Ditch in the lower right hand corner of the map above. It became a weekly horse market by 1173 and then sheep, pigs and cattle were added. Such a large open space outside the walls was convenient for tournaments and also for executions, allowing a large crowd to gather. The gallows was moved to Tyburn in the early 15th century but burnings of heretics and of women accused of witchcraft continued. Whereas a man might be beheaded or hanged, horrifyingly, women were also burned to death there for a number of offences termed treasonous, including forging currency and killing their husbands (seen as petty treason against authority). In 1652 the diarist John Evelyn recorded witnessing the burning of a woman for poisoning her husband.

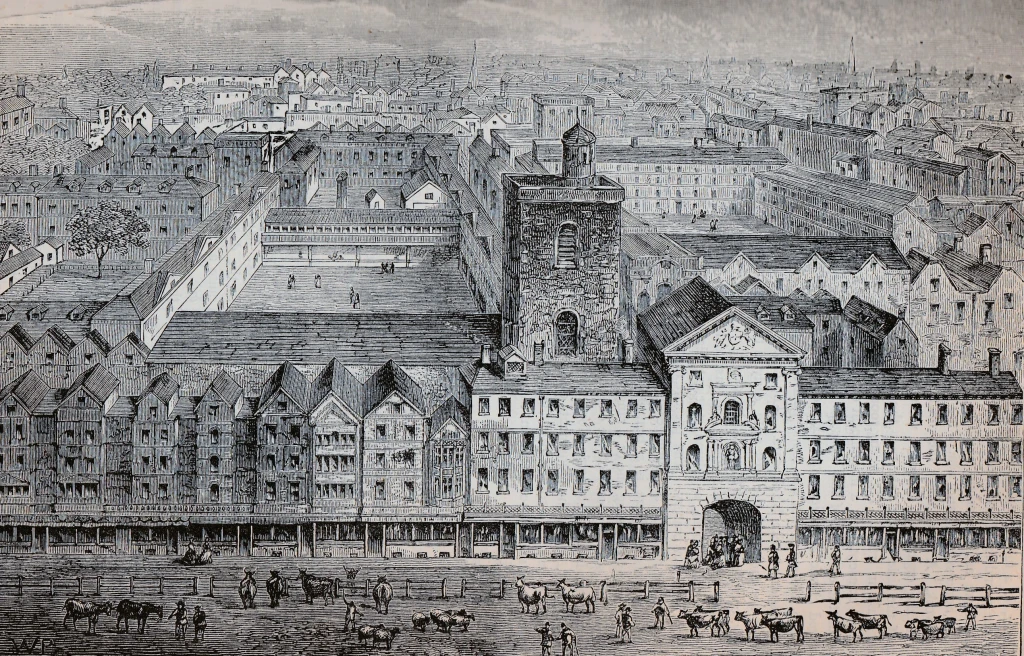

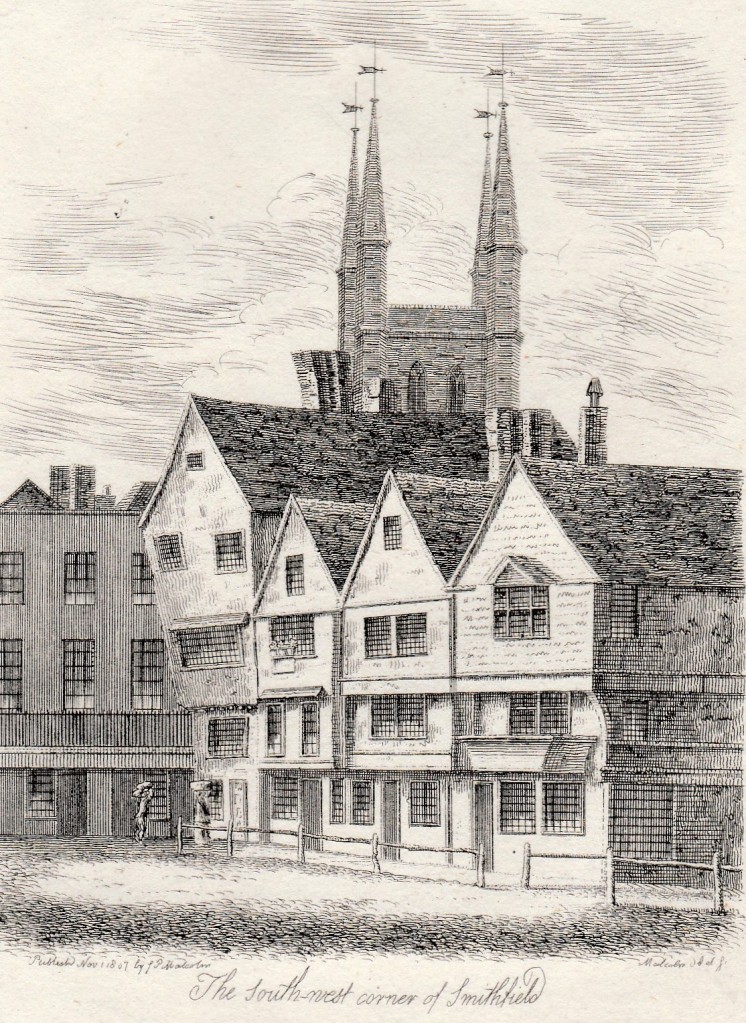

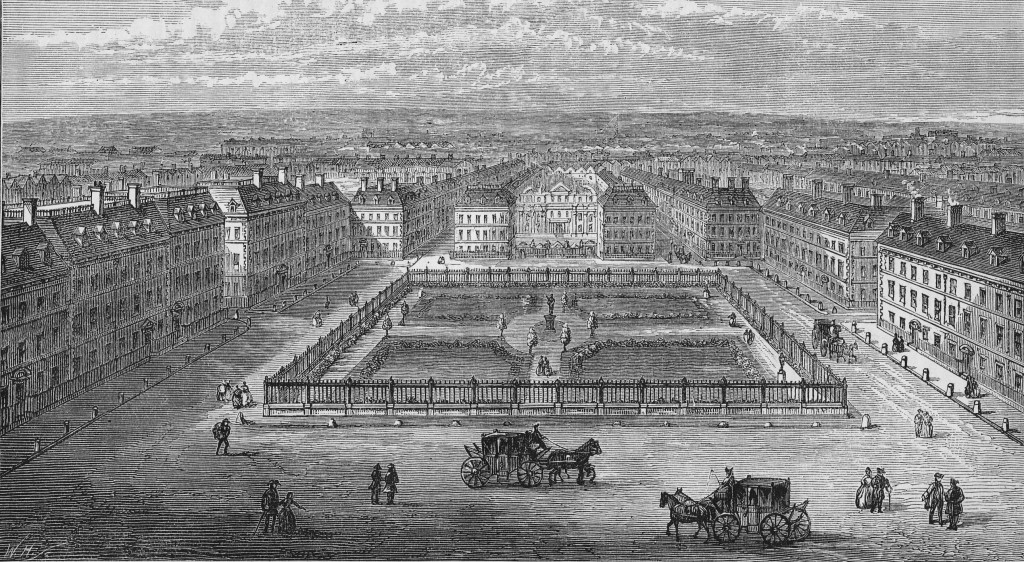

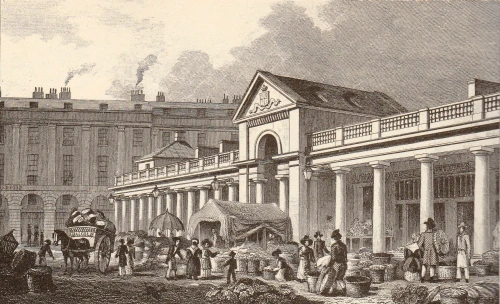

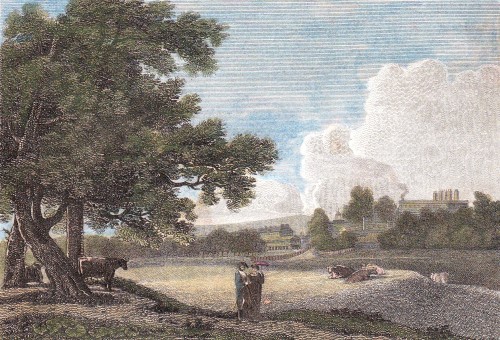

The area was a rough one, notorious for duelling and less formalised fighting, but gradually the City authorities began to bring it under control. The area was paved and a cattle market established. The print below shows St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1750 with the gatehouse and the church of St Bartholomew the Less and, in front, loose cattle, sheep and horses.

The view is of the south-east edge of Smithfield and the gate can still be seen today, although all the houses and shops on either side have been replaced.

By the time of Horwood’s map of London in the early 19th century (below) there were proper pens set out, but the market was still a chaotic, stinking, noisy and dangerous place, despite the development of the area all around with shops and houses. Animals were driven through the streets, even on Sundays, and beasts were slaughtered so that the gutters ran with blood or were blocked with entrails. In Oliver Twist Dickens wrote, “The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle… the unwashed, unshaven, squalid and dirty figures running to and fro… rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene…”

Where that central diamond of pens was is now the “Rotunda garden” a patch of green sitting on top of the circular entrance to the underground carpark and the rectangular northern area is the London Central Meat Market built between 1851 and 1899. To the west is the Poultry Market, rebuilt in 1963 after a fire. The Museum of London is planning to take over the entire range of market buildings – what will happen to the current lively weekly market, I have no idea.

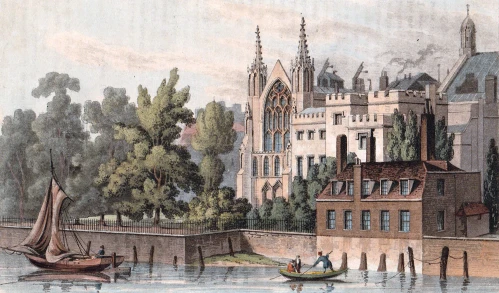

Probably the only parts of Smithfield that the pre-Victorian visitor would recognize today are the churches of St Bartholomew the Great and Lesser. In 1123 Rahere, an Augustinian, founded a priory and its church, St Bartholomew’s the Great, was built in stages, completed in 1240 with a long nave that was demolished in the 1540s after the Reformation. The choir was left as the parish church and the monastic buildings sold off. Now, the half-timbered entrance just to the south of Cloth Fair stands on the site of the original west door.

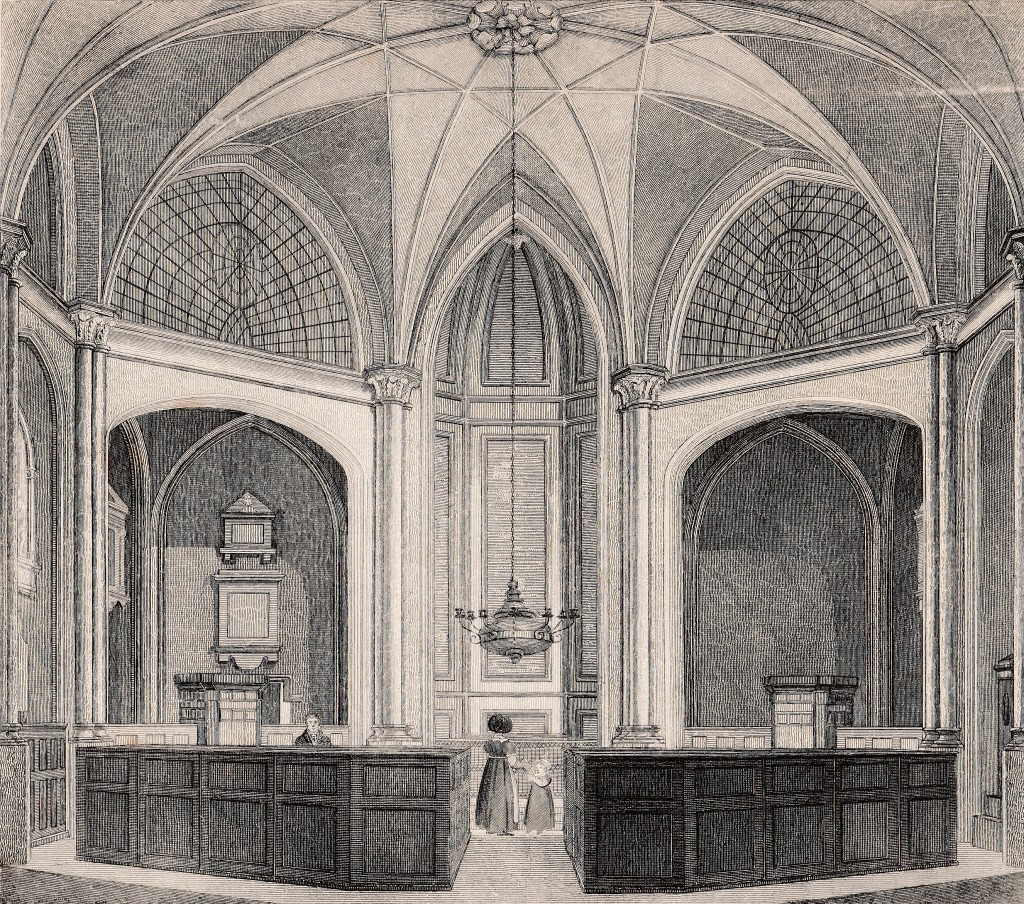

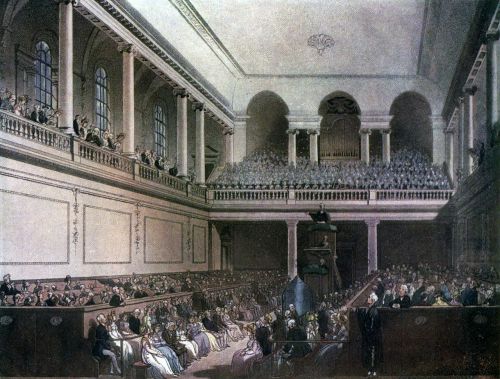

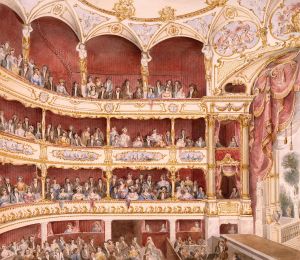

St Bartholomew the Less was a chapel for the priory, built in about 1154. Although ancient, it has had a chequered history. The print below shows the interior as remodeled by Charles Dance the Younger in 1789: the box pews have been replaced. It was heavily restored after bomb damage in the Second World War.

Rahere’s priory had a chequered life after the Dissolution. The crypt of St Bartholomew the Great became a coal store, the Lady Chapel was converted into houses plus a printer’s business where Benjamin Franklin was employed in 1725, the surrounding area held a blacksmith’s forge, a hop store, a carpenter’s workshop and stables. The Victorians restored it in 1864-56 and 1884-96 and it is difficult to imagine the state it must once have been in.

Despite the Dissolution of the Monasteries Rahere’s great work, his hospital, survives to this day. It almost closed after the Dissolution through lack of funds, but somehow kept going until Sir Richard Gresham persuaded Henry VIII to re-found it in 1544 and it has been continuously rebuilt and developed since. Known as “Bart’s” it remains on site as a specialist cancer and cardiology hospital.

One curious feature of Smithfield is the Golden Boy of Pye Corner. On the map above you can see where Giltspur Street enters at the southern end of Smithfield and to the west is an angle known as Pie, or Pye, Corner. This is where the flames of the Great Fire of London (1666) finally flickered and died out. The fact that it began in Pudding Lane and ended in Pie Corner was taken to be a warning that it had been caused by Londoner’s sinful gluttony. Actually the name derives from the Magpie Inn that once stood here and has nothing to do with pastry!

Just south of Pie Corner, on the northern corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane, stood The Fortune of War inn. it was demolished in 1910 but had a particularly lurid history. The photograph below shows it just before demolition.

As well as being a ‘receiving house’, appointed by the Royal Humane Society as the location to bring bodies of those drowned in the Thames, it was also the chief hang-out for resurrectionists, or body-snatchers, providing bodies to the surgeons of Bart’s Hospital. It seems that many of the drowned found their way into the dissecting rooms along with corpses stolen from churchyards.

In the photograph you can see the small statue of a chubby child – The Golden Boy of Pye Corner. He was rescued when the pub was demolished and is now on the corner of the new building on the site. His inscription reads:

This Boy is in Memory put up for the late Fire of London

Occasion’d by the Sin of Gluttony.

And finally, the church of St Sepulchre’s, which can be seen in the background of the print of Pie Corner, was another of Rahere’s foundations and contains the tomb of Captain John Smith, one of the founders of Jamestown and of the State of Virginia, and famous for his relationship with Pocahontas of the Powhatan tribe.

This wonderfully intricate box was shown on the Antiques Roadshow in 2020 and valued at £4-6000. It was not only innocent workboxes and ship models that the prisoners sold. An embarrassed and indignant local member of the Society For the Suppression of Vice posted two of his purchases to the London Headquarters. They appear, from the difficulty he had in wrapping them and his euphemism-laden remarks, to have been sex toys carved from bone.

This wonderfully intricate box was shown on the Antiques Roadshow in 2020 and valued at £4-6000. It was not only innocent workboxes and ship models that the prisoners sold. An embarrassed and indignant local member of the Society For the Suppression of Vice posted two of his purchases to the London Headquarters. They appear, from the difficulty he had in wrapping them and his euphemism-laden remarks, to have been sex toys carved from bone.

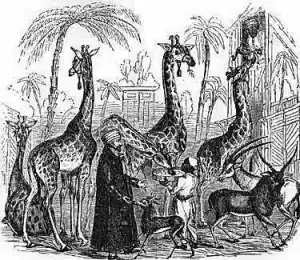

The Zoological Society of London was founded in 1826 and its collection of animals was opened in 1828 on the site at the north of Regent’s Park. There were 30,000 visitors in the first seven months. The contents of the Rooyal Menagerie from Windsor were added in 1830 and the animals from the Tower of London were moved there in 1832-4. Mr Herriott’s visitors would have been able to view monkeys, bears, llamas, zebras, kangaroos, emus, turtles, an Indian elephant, an alligator, huge snakes, Tommy the chimpanzee, four giraffes and visit the camel house (shown in the print of 1835).

The Zoological Society of London was founded in 1826 and its collection of animals was opened in 1828 on the site at the north of Regent’s Park. There were 30,000 visitors in the first seven months. The contents of the Rooyal Menagerie from Windsor were added in 1830 and the animals from the Tower of London were moved there in 1832-4. Mr Herriott’s visitors would have been able to view monkeys, bears, llamas, zebras, kangaroos, emus, turtles, an Indian elephant, an alligator, huge snakes, Tommy the chimpanzee, four giraffes and visit the camel house (shown in the print of 1835).

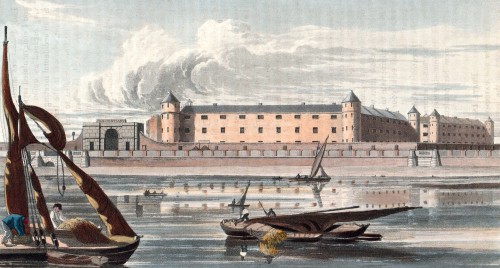

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.