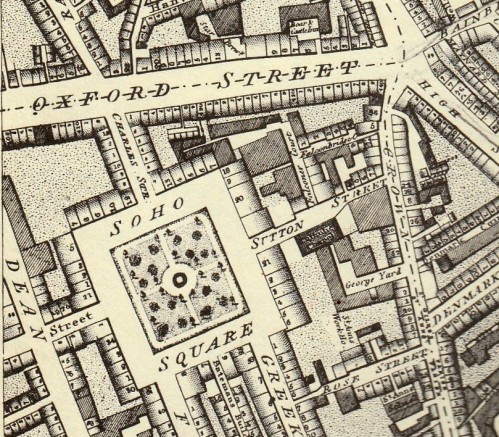

Soho Square was built in the 1680s by Richard Frith who had obtained a license indirectly from the landowner, the Earl of St Albans. The area had been farmland that had become a popular location for hunting and the most likely origin of the area’s name is that ‘So-Ho!’ was a hunting cry. By the 1670s building in the area was gaining momentum and it was popular with significant courtiers and aristocrats.

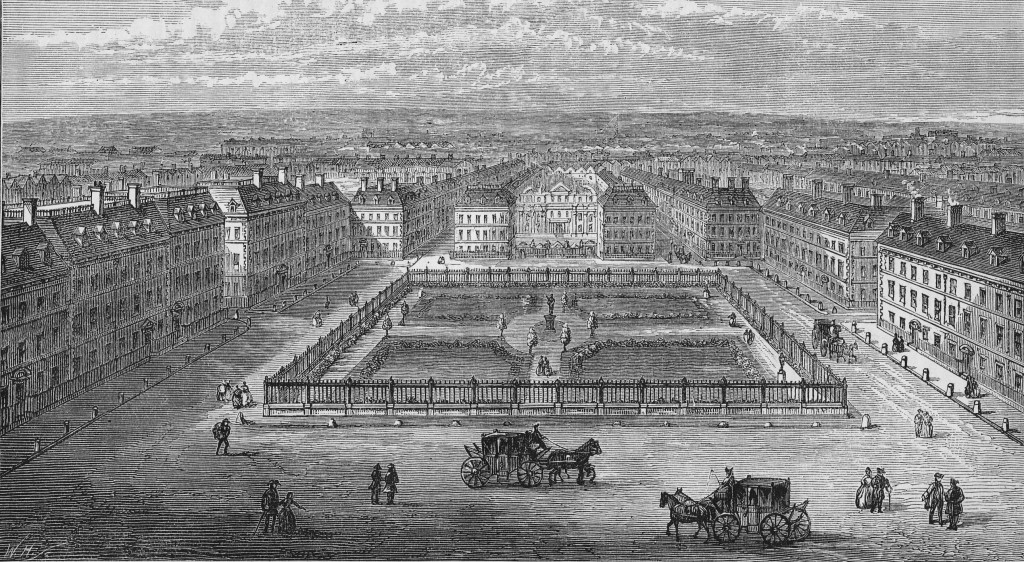

The Square had forty one houses by 1691 of which the most significant was Monmouth House on the south side, London home of Charles II’s illegitimate son the Duke of Monmouth. The print of c. 1700 below looks south across the Square towards Monmouth House with its forecourt behind railings. Monmouth was executed after his failed rebellion against his uncle, King James II, in 1685. The house was eventually demolished in 1783. In John Evelyn’s Diary he records spending the winter of 1690 ‘at Soho, in the great Square.’

The Square was also known as King Square after Charles II. In 1720 John Strype wrote that the Square ‘hath very good Buildings on all Sides, especially the East and South, which are well inhabited by Nobility and Gentry.’ He described the garden in the centre as ‘a very large and open place, enclosed with a high Pallisado Pale, the Square within neatly kept, with Walks and Grass-plots, and in the midst is the Effigy of King Charles the Second, neatly cut in Stone to the Life, standing on a pedestal.’ It stood in a basin of water with figures representing the rivers Thames, Trent, Humber and Severn. The sculptor was Caius Gabriel Cibber. Stow’s view below looks north.

In 1748 a new wall and railings were erected. By 1839 the statues was ‘in a most wretchedly mutilated state’ and in the 1870s it was removed and sold, the last owner being W.S. Gilbert of Gilbert & Sullivan fame. A half-timbered tool shed was erected in its place. The statue was returned in 1938, but without its basin. The view is looking south to where Monmouth House once stood.

The most fashionable residents abandoned Soho Square in the 1770s and moved westwards towards Mayfair but the area remained respectable and desirable and many merchants and country gentlemen had houses there, with various foreign diplomatic missions as neighbours.

By the beginning of the 19th century the residents were mainly professional men such as lawyers, doctors, architects and auctioneers. On the corner with Greek Street is what is now the House of St Barnabas, a Grade I Listed house built between 1744-7 and leased in 1754 to Richard Beckford, an immensely wealthy Jamaican plantation owner. It is now a charity for the homeless – one wonders what the slave-owning Mr Beckford would have made of that.

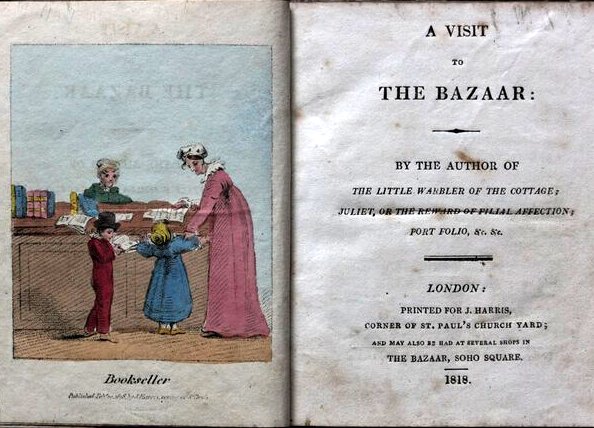

In 1816 Trotter’s, or the Soho Bazaar, was opened at what is now 4-6, Soho Square. John Trotter was an army contractor and had built numbers 4, 5 and 6 as a warehouse. Having made a vast fortune from the war he turned his warehouse into a bazaar, or indoor market, to offer an outlet for craftwork created by the widows and daughters of army officers. They could rent a counter or stall at a cost of 3d per day per foot and sold jewellery, millinery, baskets, gloves, lace, potted plants and books. There was also a druggist in the bazaar, as a charming children’s book entitled A Visit to the Bazaar (1818) shows. The little book was intended to explain the origins of such goods along with moral lessons and instructions on how to make some of them.

The highly successful venture was patronised by the royal family and lasted until 1885.

If you leave the Square today and go around to Dean Street you can peer through the iron gates at the back of the original warehouse.

The print of 1812 shows the south-west corner of the Square. Frith Street enters to the left and the entrance to Carlyle Street can be seen top right. A mixed herd of cattle and sheep are being driven towards Greek Street, perhaps heading for one of the butchers serving the numerous eating houses in the district.

Soho is a fascinating area to explore. You can find it in Walk 5 in my Walking Jane Austen’s London and Walks 5 and 6 in Walks Through Regency London and discover its treasures, even at this difficult time, with the help of StreetView.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

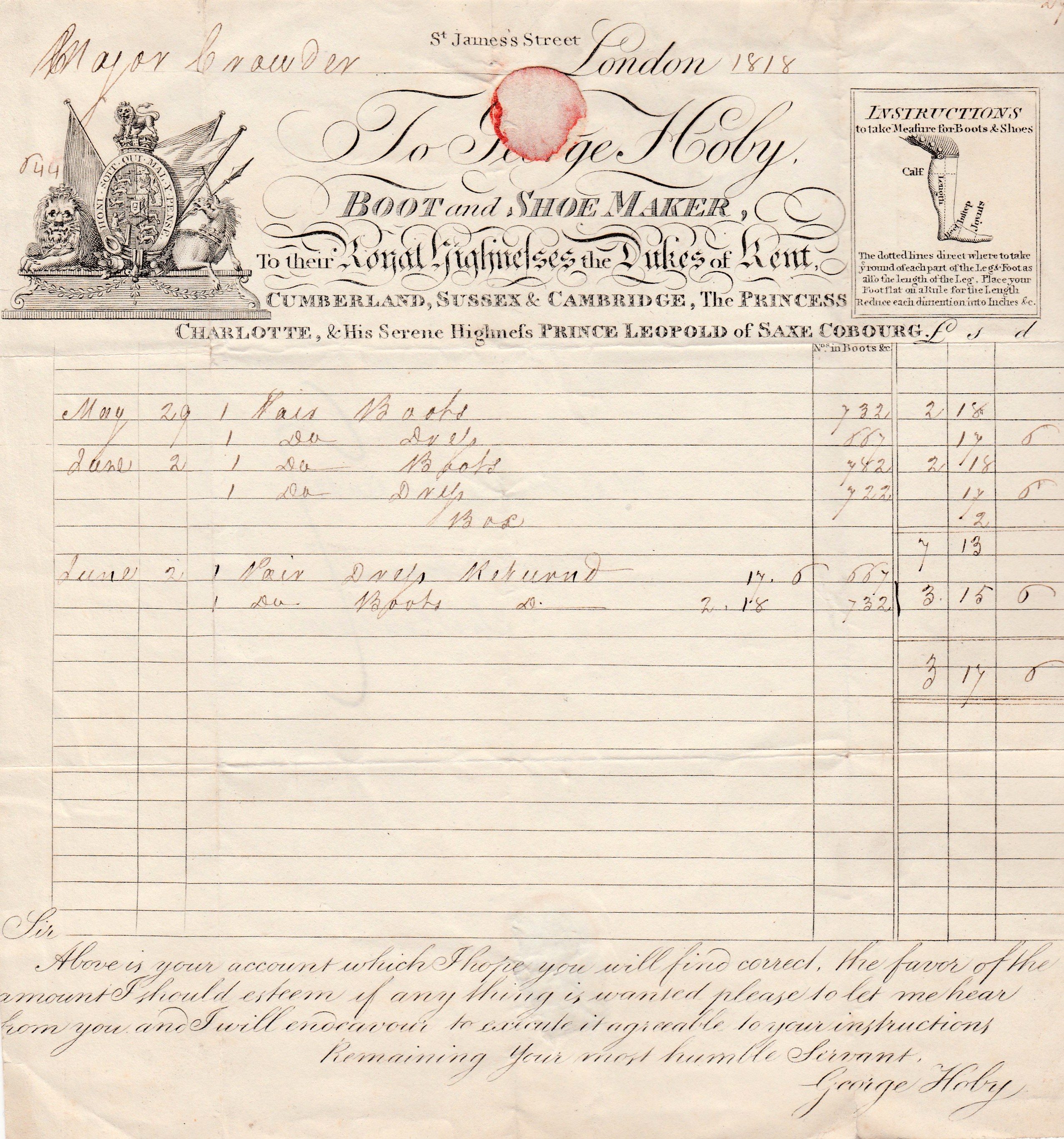

Mr George Wood lived in Blandford Court which was on the south side of Pall Mall behind Marlborough House which is within a five minute walk of Hoby’s shop which is probably why the invoice appears to have been hand-delivered. I suspect that Mr Wood was a relative of Lieutenant-General Sir George Wood, ” the Royal Bengal Tiger” and his brother Sir Mark Wood, bt. Sir Mark certainly lived in Pall Mall.

Mr George Wood lived in Blandford Court which was on the south side of Pall Mall behind Marlborough House which is within a five minute walk of Hoby’s shop which is probably why the invoice appears to have been hand-delivered. I suspect that Mr Wood was a relative of Lieutenant-General Sir George Wood, ” the Royal Bengal Tiger” and his brother Sir Mark Wood, bt. Sir Mark certainly lived in Pall Mall.