How does somewhere turn, in the space of thirty years, from a royal palace where the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was lavishly entertained to a place whose name became generic for prisons for the punishment of vagrants and fallen women?

Bridewell Palace was built for Henry VIII between 1515 and 1520. Its southern façade faced the Thames, its eastern face was on the banks of the River Fleet and it was named for the nearby holy well of St Bride and it was a typical rambling, brick-built Tudor palace around three courtyards. It was the location where Hans Holbein’s famous painting The Ambassadors was set, the venue for masques and celebrations when Charles V visited and the home of Henry’s illegitimate son Henry Blount, Duke of Richmond and Somerset.

Its days as a palace were short-lived after it served as the venue for conferences with the Papal Legate over the royal divorce and Henry’s last meeting with Catherine of Aragon in November 1529. By 1531 it was leased to the French Ambassador and it was there in 1533 that Holbein’s The Ambassadors was painted.

In 1553 Edward VI gave Bridewell away, granting it to the City of London as a home for destitute children and vagrants and as a prison for punishing disorderly and loose women and petty offenders with short periods of incarceration and regular whippings. Queen Mary confirmed Edward’s gift – perhaps not wanting to take back the place of such ill-memories of her mother.

The model of prison, hospital and workrooms proved successful enough for many others to be opened across the country, all called Bridewells. The whippings took place in public twice a week, there was a ducking stool on the banks of the Thames in 1628 and there were also stocks. The regime appears to have been one of “short, sharp shock”, although it seems doubtful that it was very successful in reducing vagrancy, petty crime and immoral behaviour with no support for its inhabitants once they were released. More fortunate were orphans of City Freemen who were accommodated here for an education before being apprenticed to a trade.

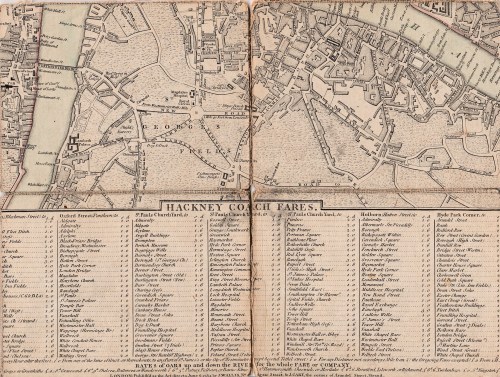

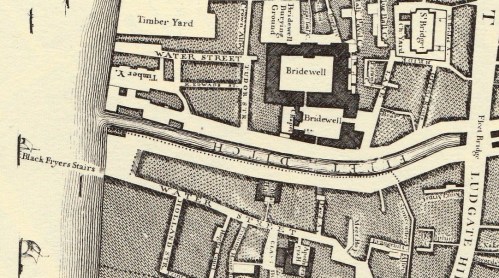

The Great Fire of 1666 destroyed much of the old palace and it was rebuilt in 1667. Judging by the print at the top of this post from a drawing by Jan Kip made in the early 18th century, some of the old Tudor palace survived. It can be seen surrounding the courtyard in the foreground with the 17th century and later additions behind. This version of Kip’s drawing was published in 1720 by John Strype and shows the view from the east – in other words, the artist is hovering above the Fleet River and looking west. The two courtyards of the rebuilt Bridewell can be clearly seen in this detail from John Rocque’s map of 1747 (below) turned to be in the same orientation.

Despite the floggings the Bridewell was more liberal than other prisons of the time – it had a doctor in 1700, seventy five years before they were appointed to prisons elsewhere, and in 1788 prisoners were not only given straw for their beds but actual beds to put it in – other gaols had neither beds nor straw. Women were not whipped after 1791. The air quality must have improved somewhat after the Fleet was covered in 1764 with the creation of New Bridge Street down to Blackfriars Bridge (1760-69).

The beds filled with straw can be seen in this print of The Pass-Room at Bridewell, 1808 from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London. Here single women with babies were locked up as punishment for their ‘loose behaviour’. The notice on the wall warns that “Those who dirts Their Bed will be Punished.”

Building work and improvements carried on until 1833 when all the Bridewells passed from local control to become part of the government’s prison system. In 1855 the prisoners were transferred to Holloway prison and the buildings were demolished in 1863/4. The only remaining fragment is the façade and gateway of 1802 which is now 14, New Bridge Street.

The outline of the site remains in the block bounded by New Bridge Street to the east, Tudor Street to the south, and Bridewell Place which wraps around the west and north sides. Tudor Street can be seen on the Rocque map and led towards one of the notorious and lawless Alsatias from which many of the inmates of Bridewell probably came.

As with Bedlam, the public could gain admittance to view the unfortunate inmates. Priscilla Wakefield, author of Perambulations in London (1814) wrote, ‘Many of the prisoners who we were permitted to see, were women, young, beautiful and depraved.’ Like much of Wakefield’s moralising writing this fills me with the desire to give her the life-chances those ‘depraved’ young women had and see how she got on!

The print below is from Ackermann’s Repository of May 1812 and shows the view looking south down New Bridge Street from what is now Ludgate Circus where Fleet Street dips down to the Fleet Valley and then rises eastwards up Ludgate Hill to St Paul’s Cathedral. Bridewell is concealed behind the furthest range of brown buildings on the right of the print.

This area is included in Walk 8 of my Walking Jane Austen’s London and Walk 9 of Walks Through Regency London.