Last week I went up the Shard on the south bank of the Thames and, knees shaking at the height, looked down on London Bridge, 800 feet below. In the photograph you can see its northern end, the Monument to the Great Fire on Fish Hill and the spire of the church of St Magnus the Martyr.

London Bridge is broken down,

Gold is won and bright renown.

Shields sounding,

War-horns sounding,

Hildur shouting in the din!

Arrows singing,

Mailcoats ringing,

Odin makes our Olaf win!

Not quite the cheery little 17th century nursery rhyme we are familiar with but a Norse poet writing of the attempt of Saxon King Ethelred the Unready (who wasn’t really Unready but Unraed-y – suffering from bad councillors) to recapture London from King Cnut (who never really believed he could hold back the tide, but chroniclers don’t seem to have any sense of irony) with the help of King Olaf of Norway in 1014.

This was the wooden London Bridge that had been rebuilt several times since the Romans left and, for centuries, was the only crossing point in London.

(Oddly, despite burning the bridge, Olaf became a popular saint. His church at the southern end of the bridge is now under an office block bearing his name.)

Even without the intervention of marauding Vikings, wooden bridges needed constant repair, so in 1176 work started on a stone bridge, completed in 1209. All the versions of London Bridge for over a thousand years have been more or less on the same spot, but we know exactly where this one, now known as Old London Bridge, was located because it survived, albeit endlessly adapted, until 1830.

The bridge had a drawbridge in it to allow taller ships to pass, gatehouses to guard it – and, from the 14th century, to act as convenient places to stick the heads and assorted limbs of traitors – and a chapel. Almost from the beginning houses and shops were built along the bridge, narrowing the roadway to between 12 and 15 feet (3.7 – 4.6 metres). After the Great Fire in 1666 when some were destroyed they were rebuilt hanging further out over the river, but even so it was hideously congested.

From 1722 tolls were charged on vehicles which meant that they tended to stop in Southwark on the southern side and unload their passengers and goods. Numerous inns grew up to deal with this business. In an attempt to control the flow on the bridge three men were employed to try and enforce driving on the left, the first time a ‘keep left’ rule was applied in England. Stonegate at the southern end was rebuilt in 1728 with a wider arch but even so, when there was a major event at Vauxhall gardens, for example, three hour traffic jams were not uncommon.

By the time Westminster Bridge opened in 1750 London Bridge was looking decidedly shabby by contrast and drastic modifications were carried out between 1757-62. All the buildings were demolished, a wider central arch was created and the bridge was widened by 26 feet (8 metres) and refaced in Portland stone. Alcoves were added along its length, some with domes, and the lighting was improved. In 1763 the Stonegate was demolished and arches made in the tower of the church of St Magnus the Martyr at the northern end for pedestrians using the widened road. The clock that overhung the roadway is still there, blocked from the river now by an ugly modern office  building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.

building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.

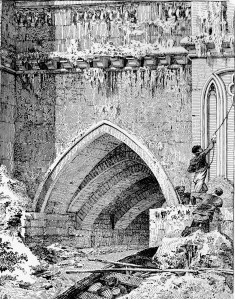

Even with the renovations the old bridge was failing and the final straw was the damage in the severe winter of 1813-14 when the last Frost Fair was held on the Thames. (The black and white print above shows one of the arches during the Frost Fair). Work began in 1824 on a new bridge, built alongside the old one so that traffic could continue. The new alignment shifted the approach to the bridge westwards from Fish Hill, site of the Monument, and obliterated the waterworks on the upstream side of the old bridge. The works had waterwheels that took 4 million gallons a day from the river to supply 10,000 customers and they can be seen on the far side in this print of 1814.

The new bridge, designed by John Rennie, opened in 1831 and the old bridge was demolished over the next two years. Rennie’s bridge was replaced in 1972 with the present structure.

So what remains of Old London Bridge? Not a lot, considering what an iconic feature of the London landscape it was for so long. One of the 18thc alcoves is in the grounds of Guy’s Hospital, two are in Victoria Park, Hackney and a fourth in the gardens of a block of flats in East Sheen. A stone from an arch is in the churchyard of St Magnus the Martyr where the clock can still be seen and you can walk through the arch in the tower. There is an excellent model of the old bridge with its houses and shops in the church and an even bigger model in the Museum of London.

If you walk into Southwark and find Newcomen Street you’ll see the King’s Arms, a Victorian pub with a fine stone coat of arms on the front. This used to say GIIR, for George II, and was fixed on the Stonegate, the entrance to old London bridge from the Southwark side, in 1728. When the gate was demolished in 1760 it was removed, the inscription changed to 1760 and GIIIR for the current king, and put up on a tavern that stood in Axe Yard.

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.  In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.

In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.