In 1836 Nathaniel Whittock’s The Modern Picture of London, Westminster, and the Metropolitan Boroughs. Containing a correct description of the most interesting objects in every part of the Metropolis; forming a complete Guide and directory for the Stranger and Resident… was published by George Virtue & Co.

I have half a dozen late Georgian & Regency London guidebooks, but this, on the verge of Victoria’s reign, is the only one that sets out itineraries for the visitor as well as describing the various buildings, parks and institutions of the Capital. I thought it would be interesting to follow his advice, and visit London right at the end of the Georgian era.

Mr Whittock begins by discussing whether it is better to take lodgings or stay at a respectable inn (not a coaching inn, or the visitor will be constantly disturbed, day and night). He concludes that:

The visitor whose time is limited, will find it better to have lodgings without board, as he can take his meals at any time or place, according to his own convenience. The visitor to the metropolis, that has no particular friends to greet him on his arrival, and whose business will only allow him to devote a few days, to the survey of the architectural beauties and splendid exhibitions which surround him on all sides, on his arrival in London, will feel the necessity of so regulating his time, that he may see the various objects that are contiguous to each other on the same day; and, supposing him to have only a week that he can spare for this purpose, we will endeavour to point out the best mode of regulating his hours, so that he may have an opportunity of seeing the greatest number of objects within that time. We will therefore suppose the visitor to have taken apartments near Charing Cross.

In the…directions, it is supposed that the party is in the middle rank of life; the same route would be pointed out to those who kept a carriage, but they would, in consequence, be enabled to visit more objects in the same time, from the facility of conveyance from one place to another.

Monday

A crowded day first ending with a visit to the theatre.

The visitor is advised to commence his perambulation of the metropolis on Monday morning, at half-past nine o’clock.

He will have ample time to see Whitehall, the statue of King James behind it, the Horse Guards, and the Admiralty.

The bronze statue of King James II now stands in front of the National Gallery. It was produced in the workshop of Grinling Gibbons and erected at the Palace of Whitehall in 1686, two years before James was deposed and fled the country. It stood behind the Banqueting House until 1898 when it was removed and spent some time being shuffled around the Capital before ending up in its present position in 1947. According to A Picture of London For 1807 it is ‘Superior to any statue in any public place in England.’

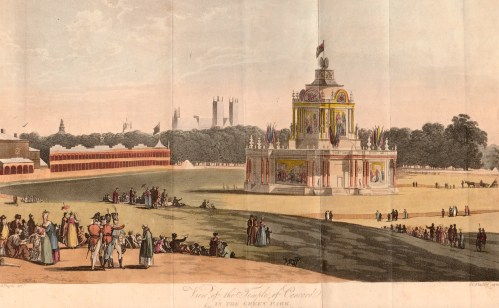

Walk into St. James’ Park, stand a few minutes to observe the military parade, which always takes place at ten o’clock.

Just such a parade can be seen in the print above of 1809, and one can still do this by walking into Horse Guards between the mounted sentries, under the arch and into Horse Guards Parade.

Walk through the Park to Storey’s Gate (the point where Horse Guards Road now meets Birdcage Walk); thence, down Princes Street (now Storey’s Gate), and he will see Westminster Abbey, and the New Westminster Hospital, to the greatest advantage.

The new Westminster Hospital opened in 1834 on the site now occupied by the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre. It was immediately struck by serious problems with its water closets and baths which failed to drain properly and caused frequent outbreaks of disease and a terrible stink.

Passing through St. Margaret’s church-yard (Above: Westminster Abbey with St Margaret’s church in front, seen from the north (1810)), he will observe the beautiful entrance to the north transept of the Abbey. The next object that will present itself, is the chapel of Henry VII., and he will arrive at Poet’s Corner at about half-past ten o’clock: the entrance to the Abbey will be open, and he will have an opportunity of hearing the cathedral service performed, and likewise of seeing the beautiful choir of the Abbey; the service is ended about eleven o’clock, and he can then survey every part of this venerable pile, which will occupy about an hour.

Passing through St. Margaret’s church-yard (Above: Westminster Abbey with St Margaret’s church in front, seen from the north (1810)), he will observe the beautiful entrance to the north transept of the Abbey. The next object that will present itself, is the chapel of Henry VII., and he will arrive at Poet’s Corner at about half-past ten o’clock: the entrance to the Abbey will be open, and he will have an opportunity of hearing the cathedral service performed, and likewise of seeing the beautiful choir of the Abbey; the service is ended about eleven o’clock, and he can then survey every part of this venerable pile, which will occupy about an hour.

This seems a very short time to view the Abbey! The visitors above, seen in 1805, appear to be taking rather more time to look around.

On leaving the Abbey, at half-past twelve, the stranger may cross the road, to the Houses of Lords and Commons and Westminster Hall, see the interior of them –

The greater part of the Houses of Parliament were destroyed by fire in October 1834, two years before the publication of this guidebook and the main text describes the makeshift debating chambers that had been made out of what remained. Westminster Hall survived the fire and was attached to the new Houses of Parliament when they were begun in 1840. The watercolour of the House of Lords from Old Palace Yard, 1834, by Robert William Billings shows the devastation. (Parliamentary copyright)

– and at one o’clock find himself on Westminster Bridge, surveying the buildings on the banks of the Thames. If this survey should engender historical reminiscences, the stranger would probably wish to visit the scene of Wolsey’s greatness, and the residence of the primate of England, Lambeth Palace; should he do so, he will find his time occupied till two o’clock.

This image of 1784 shows Morton’s Tower, the entrance to the Palace with Westminster bridge (opened 1750) in the background. The tower is instantly recognizable today, even though the embankment has been built up between it and the river and the traffic now thunders past on Lambeth Palace Road.

This image of 1784 shows Morton’s Tower, the entrance to the Palace with Westminster bridge (opened 1750) in the background. The tower is instantly recognizable today, even though the embankment has been built up between it and the river and the traffic now thunders past on Lambeth Palace Road.

To get to Lambeth Palace at this time the visitor would either have to cross Westminster Bridge and travel south down the southern bank of the Thames or go down the northern bank and take the ferry across: there was no Lambeth Bridge until 1862.

On leaving the palace, if he continues down Canterbury Place, he will, in a short time, arrive at Bethlem Hospital; to some, the interior is interesting, if so, it will occupy half an hour.

This was the New Bethlem Hospital moved from Moorfields in 1815. It was closed in 1930 and the site became a park with the centre of the old building retained as the Imperial War Museum.

Near the same spot, is the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, –

This was a pioneering institution, founded in 1792 to educate two hundred children who, up until then, had been dismissed as ‘idiots’, incapable of learning or earning their living. They were taught lip-reading, reading, writing, arithmetic and useful trades. It lay between Mason Street and Townsend Street and its modern incarnation as The Royal School for Deaf Children moved to Margate in 1902.

– the Philanthropic Asylum –

The Royal Philanthropic Society built the asylum in 1792 in an attempt to help the children of convicted criminals and street children who had resorted to begging or crime.

– and other charitable foundations, the whole of which may be visited, and the party return home over Waterloo Bridge, (This was the original 1817 bridge. The present one was opened in 1942) observe the grand front of Somerset House, and arrive at their lodgings by half-past four o’clock, dine, and finish the day by visiting Drury Lane Theatre.

Hopefully the intrepid tourist was not so worn out by their hectic sightseeing that they could not appreciate the atmosphere at Drury Lane Theatre, shown here.

If you wish to follow this route yourself you will find more details in Walking Jane Austen’s London Walk 6 or Walks Through Regency London Walk 8. The area around the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb is described in Driving Through Georgian Britain in the section on the Dover Road.

To be continued…