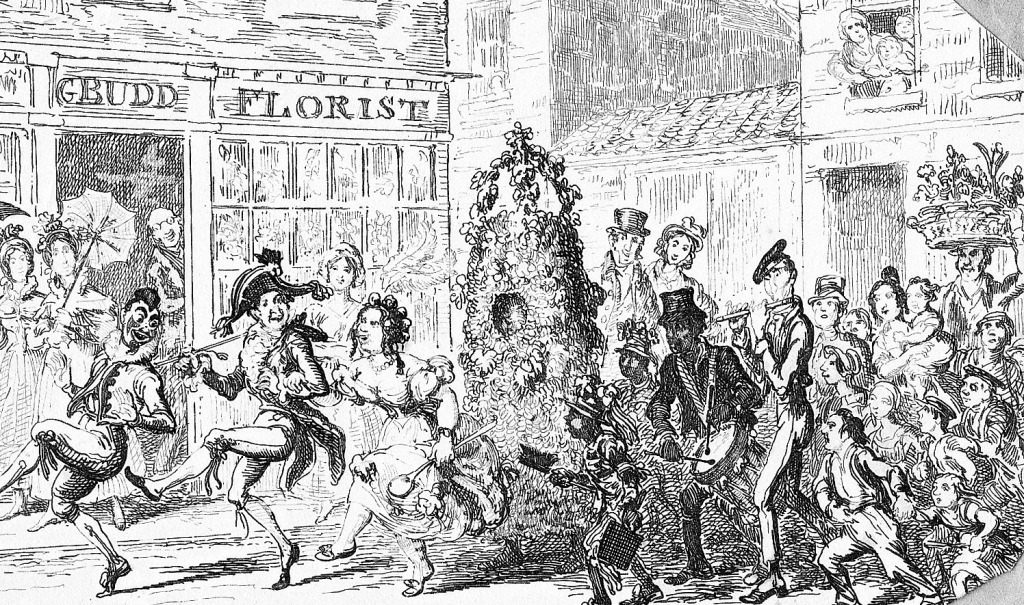

My most recent novel has a pianoforte teacher as its heroine and this prompted me to look through my collection of Regency prints to find those showing musical instruments. I have reproduced some of them here, ranging in date from 1798 to the 1820s and from the clumsy, but charming, style of The Ladies’ Monthly Museum to the beautifully detailed prints from Ackermann’s Repository.

The first is a very charming print of a rather young lady playing, I believe, a harpsichord. She looks informal and yet elegant, which reflects the strictures of ‘A Lady of Distinction’, author of The Mirror of the Graces (1811). This gave advice on ‘The English Lady’s Costume’ and also ‘Female Accomplishments, Politeness and Manners.’

On the subject of playing musical instruments it is clear that no opportunity must be lost to display the performer in the best possible light.

“Let their attitude at the piano, or the harp, be easy and graceful. I strongly exhort them to avoid a stiff, awkward, elbowing position at either; but they must observe an elegant flow of figure at both.”

Playing an instrument and singing were basic accomplishments for any young lady and she was expected to help provide the entertainment at family gatherings and social occasions. Not only was this (hopefully) pleasant for the listeners, but it demonstrated her taste and allowed her to be viewed at her best by potential suitors. The ‘Lady of Distinction’ makes this display function exceedingly clear. She considered the harp showed “a fine figure to advantage. The contour of the whole form, the turn and polish of a beautiful hand and arm, the richly-slippered and well-made foot on the pedal stops, the gentle motion of a lovely neck, and above all, the sweetly-tempered expression of an intelligent countenance; these are shown at a glance, when the fair performer is seated unaffectedly, yet gracefully, at the harp.”

A pianoforte or harpsichord, “is not so happily adapted to grace. From the shape of the instrument the performer must sit directly in front of a line of keys; and her own posture being correspondingly erect and square, it is hardly possible that it should not appear rather inelegant.” The performer is urged to hold her head elegantly and to move her hands gracefully over the keyboard.

The lady about to play the harpsichord (above) turns gracefully (or, at least, as gracefully as anyone ever does in these early Ladies’ Monthly Museum prints!) to display her gown and figure. Quite how her friend will manage to look elegant shaking the vast tambourine is not clear.

A harp and a keyboard instrument are shown in this print from a ladies’ memorandum book of 1809:

The Lady of Distinction also considers that “Similar beauty of position may be seen in a lady’s management of a lute, a guittar [sic], a mandolin or a lyre,” and fashion prints also illustrate those. In the next image, from The Lady’s Monthly Museum of 1800, the elegance is somewhat lost in the awkwardness of the drawing.

More successful is this charming scene from a memorandum book of 1819.

And Ackermann’s Repository has this from 1819. The guitar-player has a wonderful gauze overskirt and a very soulful expression.

And finally a very flowing print and a very elegant instrument from the Lady’s Magazine – I love the paw feet!

My piano teacher heroine in The Earl’s Reluctant Proposal can be found here.