This year Plough Monday, the first Monday after Twelfth-day, fell on the 10th January. Traditionally, especially in the North, the East Midlands and East Anglia, this marked the day when work resumed in the fields after the Christmas festivities, although I can’t imagine that every farm labourer was sitting about having a nice rest throughout the twelve Days of Christmas!

This chap, illustrated by W H Pyne in his Rustic Figures (1817) is clearly well dressed up for a return to work in the cold and the mud.

In the Middle Ages the church had a role in this start to the agricultural year, although the Reformation put an end to that. In 1538, Henry VIII forbade “plough lights” in churches, and Edward VI forbade the “conjuring of ploughs” – presumably their blessing by the local priest.

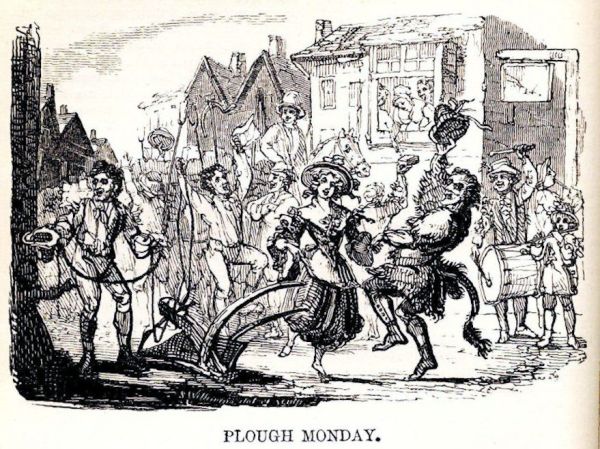

By the early 19th century, even where it survived, the custom seems to have lost all religious involvement and to have become an excuse for fun and games and collecting money as this image shows –

William Hone in his The Every Day Book (1825) describes what went on:

The first Monday after Twelfth-day is called Plough Monday, and appears to have received that name because it was the first day after Christmas that husbandmen resumed the plough. In some parts of the country, and especially in the north, they draw the plough in procession to the doors of the villagers and townspeople. Long ropes are attached to it, and thirty or forty men, stripped to their clean white shirts, but protected from the weather by waistecoats [sic] beneath, drag it along. Their arms and shoulders are decorated with gay-coloured ribbons, tied in large knots and bows, and their hats are smartened in the same way. They are usually accompanied by an old woman, or a boy dressed up to represent one; she is gaily bedizened, and called the Bessy. Sometimes the sport is assisted by a humorous countryman to represent a fool. He is covered with ribbons, and attired in skins, with a depending tail, and carries a box to collect money from the spectators. They are attended by music, and Morris-dancers when they can be got; but there is always a sportive dance with a few lasses in all their finery, and a superabundance or ribbons. When this merriment is well managed, it is very pleasing.

That last comment suggests that the festivities could get out of hand. There is some evidence that they might deteriorate into an unruly version of ‘trick or treat’ – in 1810, a farmer complained to Derby Assizes, saying that when he refused to give money the revellers ploughed up his drive, his lawn and a bench and caused twenty pounds worth of damage.

It certainly doesn’t sound as if a lot of ploughing was taking place in the fields on that day!

I have read of Plough Sunday, when the plough decorated and taken to church for a blessing, which I believe took place in parts of East Anglia well into the 19th century, before the revelry of Plough Monday.

Nowadays the Molly dancers of Cambridgeshire still celebrate Plough Monday by blessing a plough and dancing in the street. In the old days, when the plough boys were unable to plough (e.g. frozen ground) they wouldn’t get paid. They would dance on the lawns of the local gentry until they were paid to go away. If they didn’t get paid, they would plough up the lawn or the doorstep if there was no lawn. The practice was made illegal, but the plough boys had no choice but to continue, but they did so dressed as women. (hence ‘molly’). When pulled in front of the magistrate they would protest, saying “it weren’t them it were some wimmin.”