This year Plough Monday, the first Monday after Twelfth-day, fell on the 10th January. Traditionally, especially in the North, the East Midlands and East Anglia, this marked the day when work resumed in the fields after the Christmas festivities, although I can’t imagine that every farm labourer was sitting about having a nice rest throughout the twelve Days of Christmas!

This chap, illustrated by W H Pyne in his Rustic Figures (1817) is clearly well dressed up for a return to work in the cold and the mud.

In the Middle Ages the church had a role in this start to the agricultural year, although the Reformation put an end to that. In 1538, Henry VIII forbade “plough lights” in churches, and Edward VI forbade the “conjuring of ploughs” – presumably their blessing by the local priest.

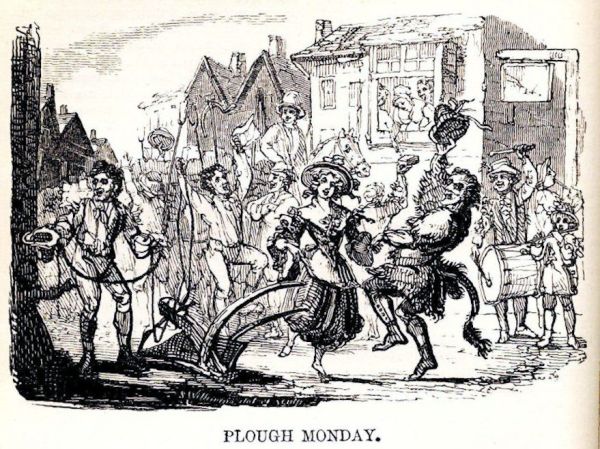

By the early 19th century, even where it survived, the custom seems to have lost all religious involvement and to have become an excuse for fun and games and collecting money as this image shows –

William Hone in his The Every Day Book (1825) describes what went on:

The first Monday after Twelfth-day is called Plough Monday, and appears to have received that name because it was the first day after Christmas that husbandmen resumed the plough. In some parts of the country, and especially in the north, they draw the plough in procession to the doors of the villagers and townspeople. Long ropes are attached to it, and thirty or forty men, stripped to their clean white shirts, but protected from the weather by waistecoats [sic] beneath, drag it along. Their arms and shoulders are decorated with gay-coloured ribbons, tied in large knots and bows, and their hats are smartened in the same way. They are usually accompanied by an old woman, or a boy dressed up to represent one; she is gaily bedizened, and called the Bessy. Sometimes the sport is assisted by a humorous countryman to represent a fool. He is covered with ribbons, and attired in skins, with a depending tail, and carries a box to collect money from the spectators. They are attended by music, and Morris-dancers when they can be got; but there is always a sportive dance with a few lasses in all their finery, and a superabundance or ribbons. When this merriment is well managed, it is very pleasing.

That last comment suggests that the festivities could get out of hand. There is some evidence that they might deteriorate into an unruly version of ‘trick or treat’ – in 1810, a farmer complained to Derby Assizes, saying that when he refused to give money the revellers ploughed up his drive, his lawn and a bench and caused twenty pounds worth of damage.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.