The 5th November is the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 when a group attempted to blow up the House of Lords, along with King James I, during the State Opening of Parliament. The aim was to install James’s nine year old daughter Elizabeth as a Catholic head of state, but the conspirators were betrayed and Guy Fawkes, who had been guarding the thirty six barrels of gunpowder stacked in the cellars under the Lords’ Chamber, was captured.

Most of the conspirators managed to get out of London but were found and, after a fight, some were killed and the others captured. At their trial in January 1606 the eight survivors, including Guy Fawkes, were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. With the popular feeling so strong against Roman Catholics at the time, celebrations on the anniversary of the discovery of the plot rapidly became a fixed part of the calendar and persisted nationally. Bishop Robert Sanderson (d.1663) preached, “God grant that we nor ours ever live to see November 5th forgotten, or the solemnity of it silenced.” By 1677 Poor Robin’s Almanac had the verse:

“Now boys with

Squibs and crackers play.

And bonfires blaze

Turns night to day.”

By the early 19th century the visible elements of the celebration – the bonfire, the effigy of the “guy” with small boys parading their own homemade versions and begging for “A penny for the guy” and the setting-off of fire crackers – were still as popular as ever. The idea of a bonfire, fireworks and the opportunity for a party was doubtless as appealing then as it is now and perhaps few people thought about what was being represented and the horrors of either the planned explosion or the hideous end of the conspirators.

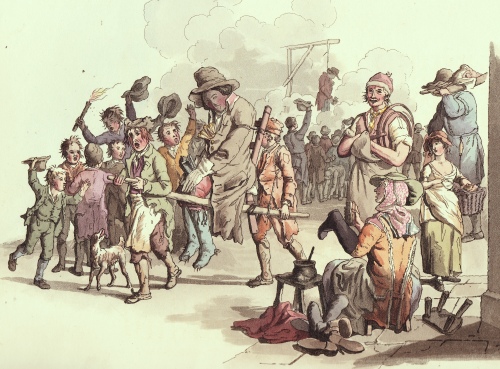

I love the detail in the picture at the top of this post. It is from Pyne’s The Costumes of Great Britain, 1805 and shows urchins parading their guy. He is dressed in old clothes with a handful of firecrackers pushed into his coat front. in the background another guy has been hung over the bonfire with his hands full of firecrackers. In the right foreground are a group of tradespeople. A man carries a joint of meat in a wooden hod on his shoulder, too preoccupied to look up, but a girl selling something from her basket, a cooper with barrel hoops over his shoulder and his tools tucked into the front of his apron and a woman blacking boots look on in amusement. The shoe-black is wearing a soldier’s uniform jacket, two scarves over a white cap and a voluminous black skirt. Her pot of blacking is on the stool beside her and she is rubbing it into a boot with a small brush.

My copy of Observations on Popular Antiquities: chiefly illustrating the origin of our Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies and Superstitions by John Brand has the following for November 5th: “It is still customary in London and its vicinity for the boys to dress up an image of the infamous conspirator Guy Fawkes, holding in one hand a dark lanthorn, and in the other a bundle of matches, and to carry it about the streets begging money in these words, “Pray remember Guy Fawkes!” In the evening there are bon-fires , and these frightful figures are burnt in the midst of them.” The original edition was 1795, but the editor of the 1813 edition has added “Mr Brand was mistaken in supposing the celebration of the fifth of November to have been confined to London and its neighbourhood. The celebration of it was general.”

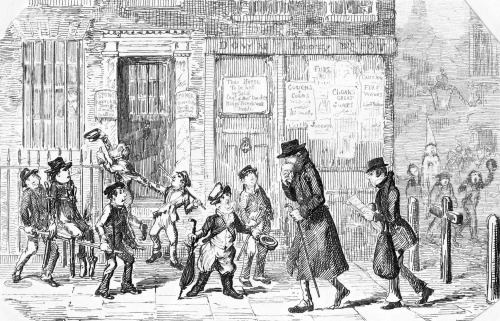

Almost thirty years after the print by Pyne was published Cruickshank’s little image for November in London shows a very similar guy, although this one has a clay pipe in his mouth. Another guy is being carried in the distance on the right and he is wearing a tall white dunce’s cap which may be intended to represent the hats worn by heretics burnt at the stake by the Spanish Inquisition.

It is obviously November – fog is swirling in the street, the figure in the centre has his nose and mouth muffled and the advertisements pasted to the boarded-up window are for cloaks, greatcoats and furs. There is also an advert for fireworks.