During a recent holiday on the Isles of Scilly I visited Tresco Abbey Gardens and discovered that they had been created by a man whose name was familiar from my childhood. Augustus Smith (1804-72) was the hero who defended the commoners rights in my home town of Berkhamstead when Lord Brownlow attempted to enclose the common land. Lord Brownlow erected steel fences, so Augustus Smith brought in a trainload of navvies who uprooted the barriers, rolled them up and dumped them on his lordship’s front lawn. Berkhamstead Common remains unenclosed to this day.

Then I read the quote under the picture of Augustus above – an image where he looks every bit the handsome and sensitive young Regency gentleman. Given that, amongst other things, I write Regency romance, I couldn’t help feeling that Lady Sophia Tower’s description of Augustus Smith sounded almost too good to be true:

“A man of good presence, above the middle height, lithe in figure, firm in step, upright in carriage, with well-cut, handsome features closely shaven (it was the English fashion then) and an eye cold, grey, observant; he looked as if he had been accustomed to command, or was born to be a ruler, whilst his gentlemanly address was prepossessing, conversation with him quickly added to the good impression he first made; nature had well moulded him, education and refinement aided him to please and to reform others.”

So, who was this paragon? Augustus was born in 1804 to a wealthy banker, raised in Berkhamstead in Hertfordshire and educated at Harrow and Oxford. He soon developed an interest in social reform and in education and these passions were allowed free rein when, in 1834, he acquired the lease of the Isles of Scilly from the Duchy of Cornwall. The islanders had suffered dreadfully from the neglect of generations of absentee landlords and were without education, support or resources. Agriculture was at a subsistence level and the only industry was the burning of kelp to create soda ash, although by the time Smith took over it has been almost overtaken by industrial processes on the mainland. A niche business supplying the very fine white beach sand for sanding wet ink was also foundering with the use of blotting paper. Most families existed on fishing and scavenging from shipwrecks.

Smith descended like an incoming monarch – his word became law on the islands, regardless of what the islanders had to say. He made education compulsory up to the age of thirteen, built a church and a pier, renovated dwellings and built himself a magnificent house on the island of Tresco next to the ruins of the 12th century abbey.

Undoubtedly he raised the living standards of the islanders, but he also created considerable controversy by what the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls his “mix of liberalism and authoritarianism….In public life his reputation was for over-persistent and often footling controversy.” Many applauded his approach, but John Stuart Mill described it as “detestable”.

He began work on the fabulous gardens on Tresco in 1834, importing plants from all over the world to create what is now an internationally famous collection.

Smith certainly expected high standards from everyone else, but I wondered about his own character. He never married, but he had two children by islander Mary Pender who was twenty years younger than Smith and whose first child was born when she was seventeen. He is also reputed to have fathered children on his domestic servants. How consensual were those relationships, given that Mary was a shop girl and the servants probably had no other employment prospects? How do you say No to the King of the Islands?

So, not the perfect hero, certainly deeply flawed, but also the man who rescued the Isles of Scilly when their inhabitants were virtually starving. The image below (unknown artist or date) seems to show a man who had no doubts about his own rightness!

After my last visit to The Isles of Scilly I wrote a trio of books linked by the shipwreck of an East Indiaman: you can find the Danger and Desire series here.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

You put your hand into the hole and then drop the ball to either left or right into the appropriate drawer – the ‘sleeve’ is long enough to conceal any movement of your arm which might give away which option you are taking. Once all the members have dropped in their ballots it was simply a case of pulling out the drawers and seeing the result.

You put your hand into the hole and then drop the ball to either left or right into the appropriate drawer – the ‘sleeve’ is long enough to conceal any movement of your arm which might give away which option you are taking. Once all the members have dropped in their ballots it was simply a case of pulling out the drawers and seeing the result.

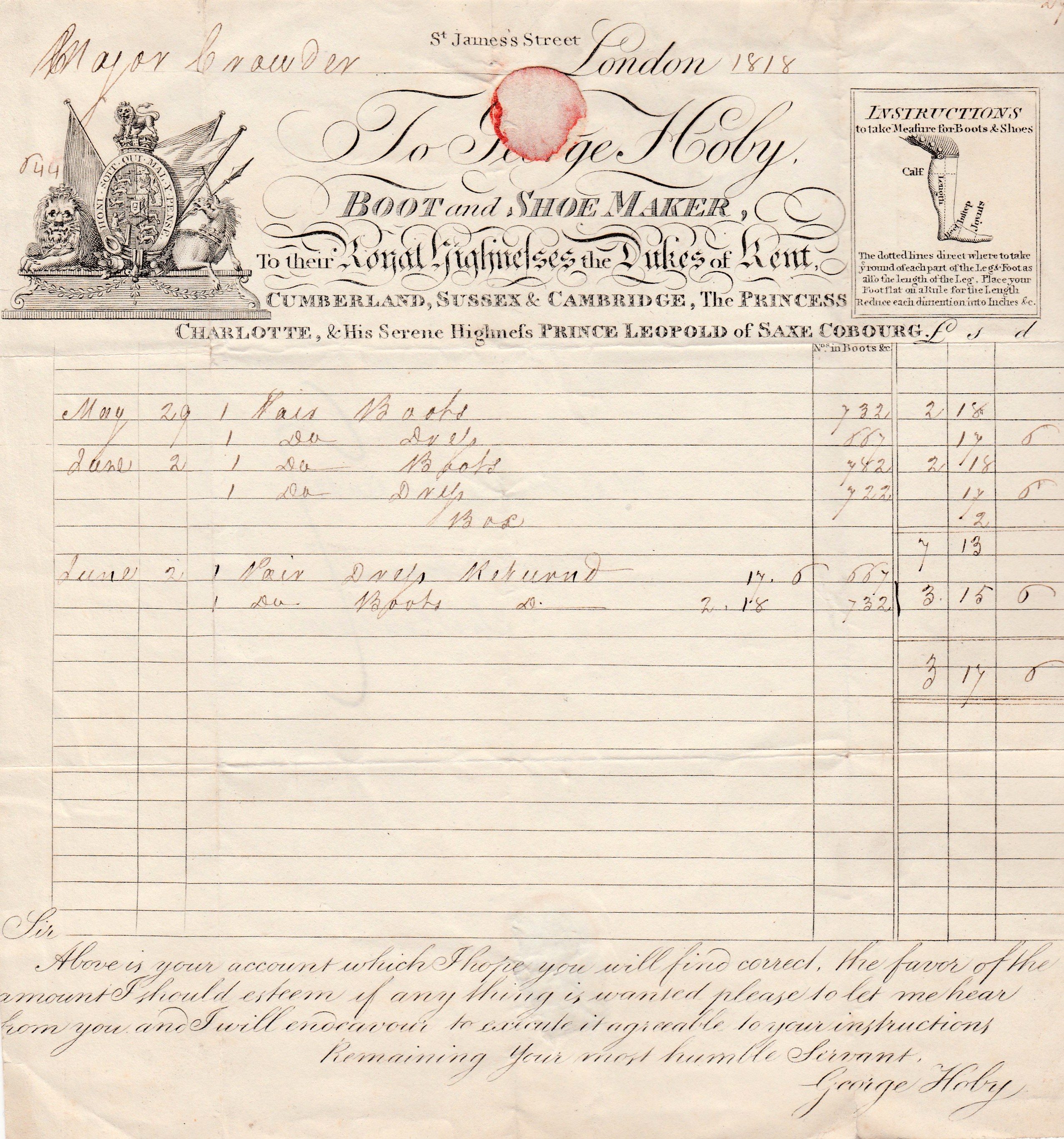

Mr George Wood lived in Blandford Court which was on the south side of Pall Mall behind Marlborough House which is within a five minute walk of Hoby’s shop which is probably why the invoice appears to have been hand-delivered. I suspect that Mr Wood was a relative of Lieutenant-General Sir George Wood, ” the Royal Bengal Tiger” and his brother Sir Mark Wood, bt. Sir Mark certainly lived in Pall Mall.

Mr George Wood lived in Blandford Court which was on the south side of Pall Mall behind Marlborough House which is within a five minute walk of Hoby’s shop which is probably why the invoice appears to have been hand-delivered. I suspect that Mr Wood was a relative of Lieutenant-General Sir George Wood, ” the Royal Bengal Tiger” and his brother Sir Mark Wood, bt. Sir Mark certainly lived in Pall Mall.

Finally, and most regally, there is The Cut Visible, the cut so blunt and obvious that no-one could mistake it. The Prince Regent’s version of this is known as Rumping. If he wishes to indicate that some former acquaintance is now persona non grata then Prinny simply turns his back on them at the last moment as they approach him. The unfortunate cuttee is then presented with a fine view of the expansive royal backside. (A fine view of the Royal Rump can be seen in this detail from a Cruickshank cartoon of 1819)

Finally, and most regally, there is The Cut Visible, the cut so blunt and obvious that no-one could mistake it. The Prince Regent’s version of this is known as Rumping. If he wishes to indicate that some former acquaintance is now persona non grata then Prinny simply turns his back on them at the last moment as they approach him. The unfortunate cuttee is then presented with a fine view of the expansive royal backside. (A fine view of the Royal Rump can be seen in this detail from a Cruickshank cartoon of 1819)