“This square is esteemed the next in beauty, as it is in extent, to Grosvenor-square. It is built with more regularity than the latter: but the very uniformity of the houses, and the small projection of the cornices, are not favourable to grandeur and picturesque effect.”

This modified rapture comes from the beginning of the article in Ackermann’s Repository of August 1813 accompanying this print of the north side of Portman Square.

The square was begun in 1764 as a speculative development by John Berkely Portman, MP, for whom it is named. It rapidly became one of the most fashionable addresses in London and ‘The residence of luxurious opulence,’ according to Priscilla Wakefield, the Quaker philanthropist and writer of children’s non-fiction books.

Amongst its residents was Lord Castlereagh, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, closely associated with Lord Liverpool’s repressive government. The portrait below is after the original by Lawrence. Shelley wrote of him in The Mask of Anarchy,

‘I met Murder in the way –

He had a mask like Castlereagh.’

At the time of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 a furious mob attacked his house and smashed the windows.

Considerably more liberal was Mrs Elizabeth Montagu who lived in the house built for her 1777-82 on the north-west corner, now replaced by the massive block of the Radisson Blu hotel. Mrs Montagu was an intellectual – a ‘blue stocking’ – and philanthropist.

Every May Day she gave a roast beef and plum pudding dinner to chimney sweeps and their apprentices, the unfortunate ‘climbing boys’.

As the Ackermann article reports, these were children “doomed to a trade at once dangerous, disagreeable, and proverbially contemptible, the chimney-sweepers.”

May Day appears to have particular significance for chimney sweeps. In Brand’s “Observations on Popular Antiquities…Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies and Superstitions.” (1813) he notes “The young chimney-sweepers, some of whom are fantastically dressed in girls’ clothes, with a great profusion of brick dust by way of paint, gilt paper etc, making a noise with their shovels and brushes, are now the most striking objects in the celebration of May Day in the streets of London.” The little lad holding his brush in the centre foreground of this print by Cruickshank certainly seems cheerful enough.

At Mrs Montague’s feast tables were set out in the gardens and “servants in livery [waited on] the sooty guests, with the greatest formality and attention.” Great crowds watched the gathering, “highly diverted with the many insolent airs assumed on the joyful occasion by the gentlemen of the brush, who, bedizened in their May-day paraphernalia, would rush through the crowd of spectators with all the arrogance of foreign princes.”

The reality of their everyday lives is more honestly seen in another Cruickshank print which shows how a boy trapped and suffocated in a chimney was removed. (The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album. Arranged by James Montgomery. Illustrations by George Cruickshank (1824)).

In the south-west corner was the residence of Monsieur Otto, negotiator for the French of the Peace of Amiens, signed 27 March 1802. He displayed illuminations in the square to mark the event and they can be seen in a print in the British Museum collection.

Ackermann’s also records that the residence of the Ottoman ambassador to the British court was on the west side of the square and, “Whilst the ambassador continued here, this square was the resort of all the beauty and fashion of this district of the metropolis.”

The square has suffered from bombing and redevelopment but number 20, Home House designed by Robert Adam, survives. In the print of the square above it is the tallest block.

Orchard Street leads southwards out of the square in the south-east corner. This is where Jane Austen’s aunt Mrs Hancock and her cousin Eliza were living in August 1788 when Jane dined with them during her first recorded visit to London.

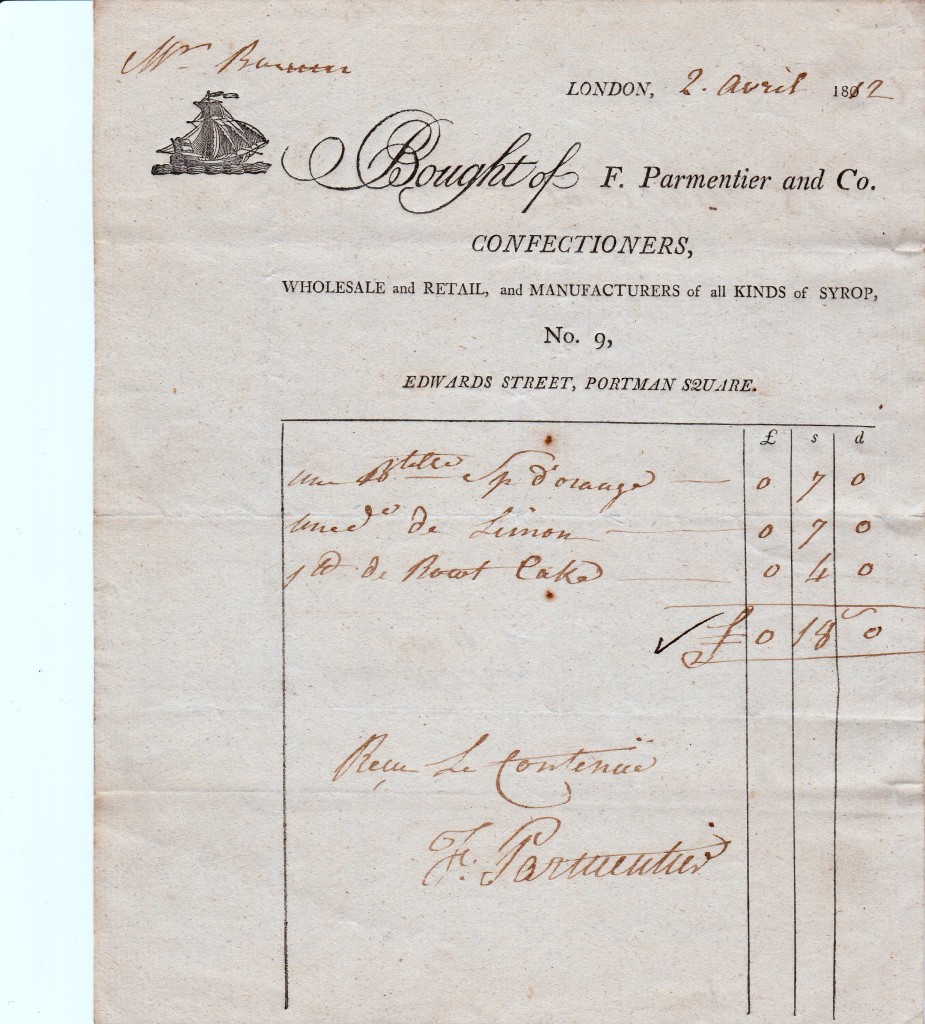

Going east from the same corner was Edwards Street, now included in Wigmore Street, the location of Society caterer Parmentier.

From the north east corner Baker Street runs north. In the guide book The Picture of London, Baker Street was described as “perhaps the handsomest street in London.” It can no longer be said to be of much interest, except to record that it led to the Hindoostanee Coffee House in Baker Street, the site of the first Indian restaurant in London. It was opened in 1810 by Sake Dean Mohammed who became famous in Margate for his lavish bath house. The coffee house was less successful and closed within the year. You can read more about him here.

The area around Portman Square forms Walk Two in my Walking Jane Austen’s London.

The image above is from La Belle Assemblée for October 1809 and shows ‘Sea Coast Promenade Fashion.’

The image above is from La Belle Assemblée for October 1809 and shows ‘Sea Coast Promenade Fashion.’ Somewhat later – I do not have a date for this, but it is c1820 – is this ‘Walking Dress’ from Ackermann’s Repository. I can’t help feeling that this lady is looking positively shifty as she readies her telescope.

Somewhat later – I do not have a date for this, but it is c1820 – is this ‘Walking Dress’ from Ackermann’s Repository. I can’t help feeling that this lady is looking positively shifty as she readies her telescope.

What did one wear to get to and from those bathing machines? The ever-inventive Mrs Bell produced a magnificent ‘Sea Side Bathing Dress’ for the August 1815 edition of La Belle Assemblée. This is not the costume for entering the sea but for wearing to get there, and it is lavishly trimmed in drooping green, presumably to imitate seaweed. Note the bag she is carrying. This contains Mrs Bell’s ‘Bathing Preserver’ which she produced in 1814. You can see it in its bag again below (La Belle Assemblée September 1814). Here the lady is wearing ‘Sea Side Morning Dress’ with ‘Bathing Preserver. Invented & to be had exclusively of Mrs Bell, No.26 Charlotte Street, Bedford Square.’ The Preserver is in the bag lying beside her chair.

What did one wear to get to and from those bathing machines? The ever-inventive Mrs Bell produced a magnificent ‘Sea Side Bathing Dress’ for the August 1815 edition of La Belle Assemblée. This is not the costume for entering the sea but for wearing to get there, and it is lavishly trimmed in drooping green, presumably to imitate seaweed. Note the bag she is carrying. This contains Mrs Bell’s ‘Bathing Preserver’ which she produced in 1814. You can see it in its bag again below (La Belle Assemblée September 1814). Here the lady is wearing ‘Sea Side Morning Dress’ with ‘Bathing Preserver. Invented & to be had exclusively of Mrs Bell, No.26 Charlotte Street, Bedford Square.’ The Preserver is in the bag lying beside her chair.

Philip Astley, a six foot tall cavalryman, rose to the rank of sergeant major and left the army in 1768. With two horses he began to give unlicensed shows of horsemanship and riding lessons on open ground in Southwark. According to the London Encyclopedia he obtained a licence with the patronage of George III after subduing an out of control horse near Westminster Bridge. This enabled him to open ‘The Royal Grove’, a canvas-covered ring close to the southern end of Westminster Bridge in 1769. Today if you stand on the bridge and look towards St Thomas’s Hospital on the far bank you can see a patch of trees where the hospital gardens are. This is approximately the location of Astley’s, shown below in 1777.

Philip Astley, a six foot tall cavalryman, rose to the rank of sergeant major and left the army in 1768. With two horses he began to give unlicensed shows of horsemanship and riding lessons on open ground in Southwark. According to the London Encyclopedia he obtained a licence with the patronage of George III after subduing an out of control horse near Westminster Bridge. This enabled him to open ‘The Royal Grove’, a canvas-covered ring close to the southern end of Westminster Bridge in 1769. Today if you stand on the bridge and look towards St Thomas’s Hospital on the far bank you can see a patch of trees where the hospital gardens are. This is approximately the location of Astley’s, shown below in 1777. Astley’s fame spread rapidly and in 1772 he performed before King Louis XV at Versailles. Patty, his wife, was also an accomplished rider. At first she assisted by beating out rhythms on a large drum but she soon joined in with horseback tricks including riding with a “muff” of swarms of bees over her hands and arms. Her husband began to incorporate comedy into his tricks, including his most famous act, The Tailor of Brentford.

Astley’s fame spread rapidly and in 1772 he performed before King Louis XV at Versailles. Patty, his wife, was also an accomplished rider. At first she assisted by beating out rhythms on a large drum but she soon joined in with horseback tricks including riding with a “muff” of swarms of bees over her hands and arms. Her husband began to incorporate comedy into his tricks, including his most famous act, The Tailor of Brentford.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

hand the sea-water cure sounds as though it would be helpful for what ails him. His wife keeps leaving prints of craggy cliffs and tossing waves about, so he supposes it would keep her happy and the rest of the family seemed keen enough. He would think on it.

hand the sea-water cure sounds as though it would be helpful for what ails him. His wife keeps leaving prints of craggy cliffs and tossing waves about, so he supposes it would keep her happy and the rest of the family seemed keen enough. He would think on it. and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of

and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.  In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.

In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.