I was puzzling the other day over whether it would be more correct for my heroine to be wearing a corset or stays – or what exactly jumps were – so I did a little research.

To begin with Stays: the Oxford English Dictionary has “Stays (also a pair of stays). A laced under-bodice, stiffened by the insertion of strips of whalebone (sometimes of metal or wood) worn by women (sometimes by men) to give shape and support to the figure: = CORSET.”

The word is used in the sense of ‘staying’ something – securing it or holding it firm.

The earliest use given is 1608 and the use of the plural “is due to the fact that stays were originally (as they still are usually) made in two pieces laced together.” Presumably in the same way that we speak of a pair of drawers, which used to consist of two separate legs tied at the waist.

As for the Corset, the OED goes back to 1299 for the first use of the word, although that was a medieval outer garment. The earliest example they give for it as an undergarment is in The Times for 1795 – “Corsettes about six inches long [presumably this means the depth top to bottom], and a slight buffon tucker of two inches high, are now the only defensive paraphernalia of our fashionable Belles.” From the spelling and the timing it would appear that this term comes via the French and relates to the light, often uncorsetted, Empire fashions of the Revolution. They also quote a patent application of 1796 for “An improvement in the making of stays and corsettes.”

And finally Jumps. A jump was man’s short coat (17th & 18thc) also used generally, in the plural, for clothes, especially in country areas. But also a “kind of under (or undress) bodice worn by women, esp. during the 18th century, and in rural use in the 19th; usually fitted to the bust, and often used instead of stays. From c.1740 usually as plural jumps (a pair of jumps).” Oxford English Dictionary.

They seem to have been laced at the front, often had shoulder straps and were only lightly boned, if at all. This made them particularly suitable for women performing manual work and for nursing mothers.

A pair of jumps can be seen here c. 1770. The jumps are on the far left, with a corset hanging next to them.

For those British ladies not following extreme French fashion, the ‘long stay’ was the most used until about 1810. It is well illustrated in the satirical drawing at the top of the page: Gilray, Progress of the Toilet: The Stays published in February 1810. It laces right up the back (with one lace), covers the hips and is made to cup and support the bust. Unusually for this early date the lady is wearing knee-length drawers.

The fabric for long stays was jean (a strong twilled cotton) or buckram (a stiff cotton or linen soaked in a size such as wheat starch).

At this period, before the mass production of metal eyelets, the lace holes were simply strengthened with buttonhole stitch and would not take the strain of ferociously tight lacing. Shape therefore depended a great deal on the original cut of the garment and on its stout cloth and boning.

Many styles of stays were invented, experimenting with various fabrics for more flexibility, support and comfort and some stay-makers advertised more than fifteen varieties.

The extreme compression of the long stay gave rise to various health concerns, to say nothing of discomfort, and from about 1810 the short stay came into fashion, along with the ‘Divorce Corset’ designed to push the breasts apart.

Even with the short corset, there were critics. C. Willett Cunnington quotes one (unfortunately without attribution) as ranting in 1811: “…in eight women out of ten, the hips squeezed into a circumference little more than the waist; and the bosom shoved up to the chin, making a sort of fleshy shelf disgusting to the beholders and certainly most incommodious to the wearer.”

By September 1813 Jane Austen was writing to her sister Cassandra with the latest fashion news from London. “I learnt from Mrs Tickar’s young Lady [presumably her lady’s maid], to my high amusement, that the stays are now not made to force the Bosom up at all: that was a very unbecoming, unnatural fashion.”

The short stays were much more like a modern bra and did nothing to restrain the stomach or hips. A French pair from 1810 are shown above in a print designed to show how easy they were to put on.

This pair, for which I do not have a source, are laced up at the front.

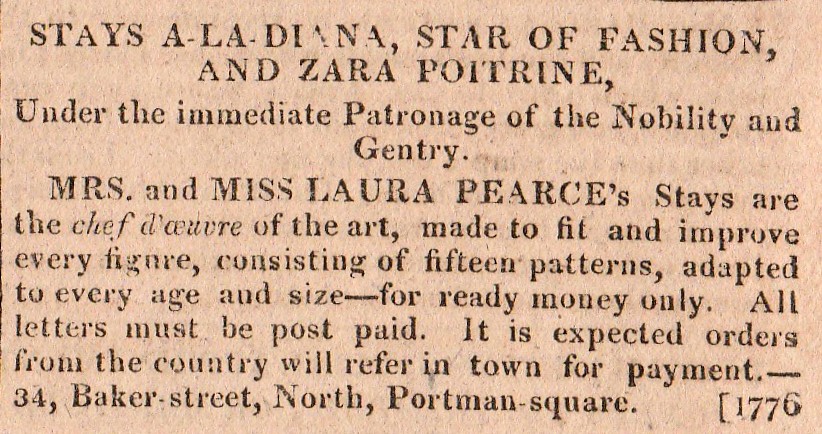

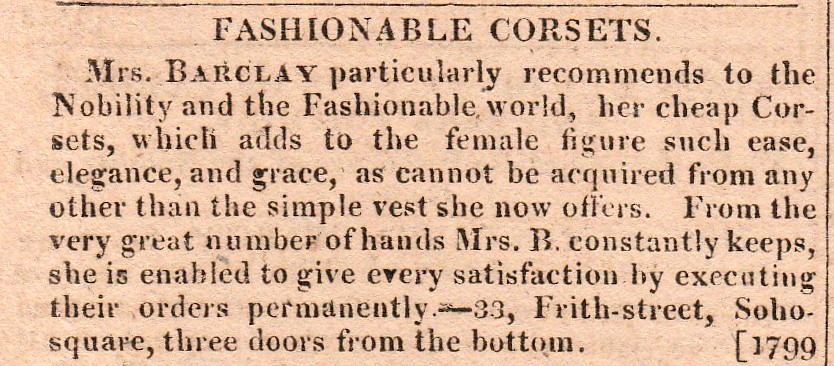

The advertisements in La Belle Assemblee show how stays were promoted, with makers striving to differentiate their products.

In February 1809: “The much approved entire new Cotton and Brace Corset, invented and made only by Misses Linckmyers, No.12, Frith-street, Soho-square….entirely obviate every inconvenience frequently attending long stays…”

In April the same year these two adverts appeared:

Mrs Barclay is also operating in Frith Street, a short distance from the Misses Linckmyers. Not only are her corsets ‘fashionable’, but they are also ‘cheap’ and the increasing desire for comfort can be seen in the reference to ‘the simple vest’.

After all that my heroine is definitely opting for a short corset, if not a nice comfy pair of jumps!