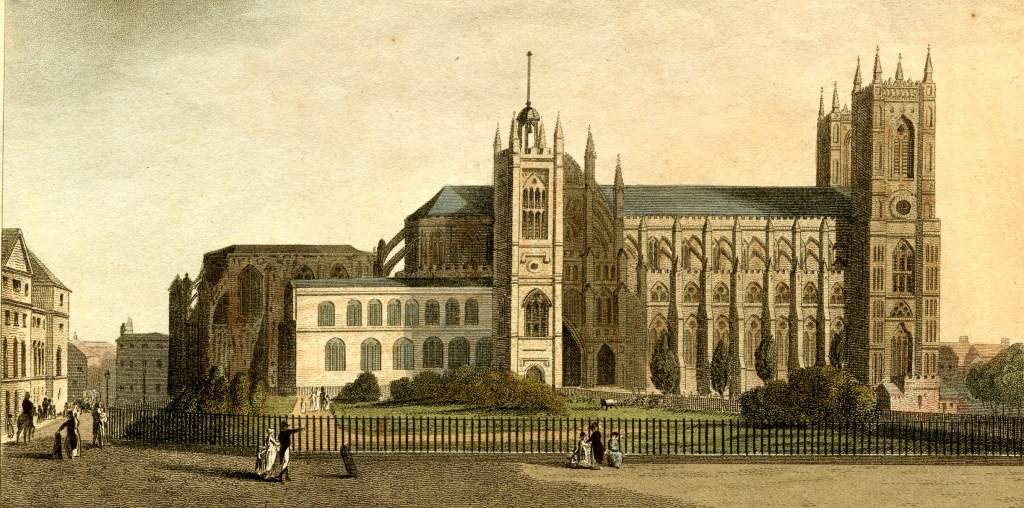

Planning a coronation must be a huge logistical operation. It would have been even worse in the days before rapid communications and computers.

Here are seven Westminster Abbey coronations with some lessons arising from their more difficult moments.

William the Conqueror: brief your bodyguard properly

William had a large force of Norman soldiers outside Westminster Abbey when he was being crowned on Christmas Day 1066. They were so alarmed by the shouts of acclamation from inside the building that they attacked the Saxons outside and set fire to houses. Not the best start to Saxon-Norman relations at the beginning of the reign…

The image from the Bayeux Tapestry shows William with his half-brother Bishop Odo on his right.

James II: Beware of bad omens

James, the younger brother of Charles II, was crowned on 23rd April 1685. Because he was a Roman Catholic he had been anointed and crowned the previous day during a Catholic ceremony in the chapel at Westminster Palace and there was no communion service as part of the Abbey ceremony.

It is said that the crown seemed very precarious on James’s head and was slipping – perhaps because it had been made for his brother and didn’t fit well. (Charles had a complete regalia made to replace the ancient one melted down or sold by the Parliamentarians.)

Another bad moment was said to have been the wind tearing the Royal Standard at the Tower of London at the moment of crowning.

How much of that was hindsight or pure fiction we’ll never know – but James reigned for only four years before being supplanted by his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange.

James II in coronation robes painted by Lely.

George II: wear manageable clothing

George and Queen Caroline were crowned 11th October 1727. Caroline’s gown was heavily encrusted with jewels – so heavily, in fact, that a pulley system had to be installed so that she could kneel down. As she had to do this several times in the course of the ceremony I am disappointed that I can’t find an image of this. It can hardly have added to the dignity of the occasion. The Coronation medal shown below clearly depicts the throne that will be used again for the coronation of Charles III.

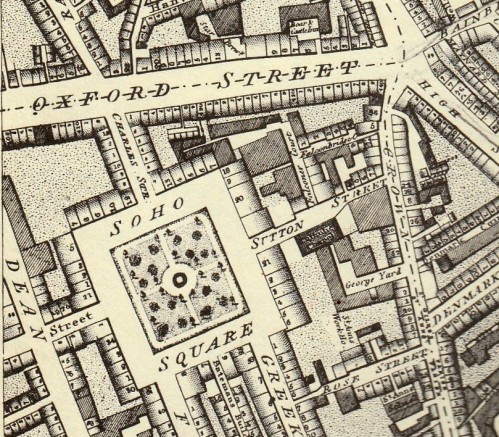

George III: avoid sedan chairs

George III and Queen Charlotte were crowned on 22nd September 1761. They made the first part of the journey from St James’s Palace to Westminster Hall in sedan chairs, which must have lacked a certain something as far as the watching crowds were concerned, and must have been a dreadful crush considering the lavish clothes they were wearing.

They walked from Westminster Hall to the Abbey at 11am, so at least we know that Charlotte wasn’t as encumbered by her robes as her predecessor had been. Everything took so long that they were not crowned until 3.30pm, but the lavish coronation banquet in the Hall afterwards must have gone some way to reviving the guests. George and Charlotte are shown below in their coronation robes.

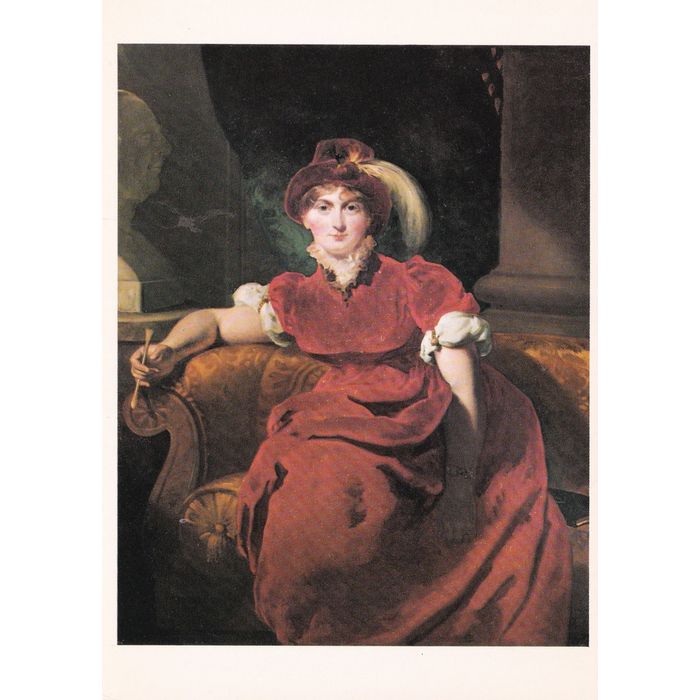

George IV: don’t make a spectacle of your wife

After long years waiting as Prince Regent, George was finally crowned George IV on 19th July 1821 in a lavish and incredibly expensive ceremony designed by himself. It even involved a brand new crown.

I have written about the procession here, but before the start of that there was a ghastly scene with his estranged Queen, Caroline of Brunswick. She had been barred from attending the ceremony but arrived in her carriage anyway.

She was accompanied by Lord Hood who escorted her to the door and announced to the doorkeeper, “I present to you your Queen, do you refuse her admission?”

The doorkeeper said he couldn’t let anyone in without a ticket. Lord Hood had a ticket, but for one person. Caroline wasn’t prepared to use it and enter unescorted.

At that point the situation deteriorated badly. The Queen shouted, “The Queen! Open!” and the pages opened the door. “I am the Queen of England!” she declared, to which an official ordered the pages, “Do your duty… shut the door!”

She was turned away from the west door of the abbey by a group of bouncers – professional bare-knuckle fighters – who had been hired to prevent her entry. Seriously obese, in great emotional distress and despite the great heat of the day, she ran from one door to another around the Abbey, hammering on them and screaming to be allowed in. “I am Queen of England!” she cried as door after door was slammed in her face.

Eventually she had to admit defeat and was driven away in her carriage. Nineteen days later she was dead.

William IV: avoid penny-pinching and don’t fall out with the family

William, George IV’s younger brother, was crowned on 8th September 1831. He was a bluff, no-nonsense naval man and wore his admiral’s uniform for the ceremony. Unlike his brother George, William was very careful with money and decided there would be no banquet as this was too extravagant – the event went down in history as The Penny Coronation.

The day was marred by a furious family spat. The Princess Victoria, the child of his late younger brother Edward, was the childless King’s heiress presumptive, but the King and her domineering mother, the Duchess of Kent, were at loggerheads. As a result he said that in the coronation procession the Princess must walk behind her uncles, the surviving Royal Dukes, and not immediately behind himself and Queen Adelaide. Her mother promptly announced that this was such an insult that neither she nor Victoria would attend.

“Nothing could console me,” Victoria wrote, “not even my dolls.”

Queen Victoria: rehearsals are vital

There appears to have been no rehearsal for Victoria’s coronation – at one point the Queen turned to Lord John Thynne and whispered, “Pray tell me what I am to do, for they [the officiating clergy] do not know.”

The Bishop of Durham handed her the orb at the wrong time: she found it so heavy she could hardly hold it. The Archbishop of Canterbury forced the ring on her wrong finger causing her intense pain.

Lord Rolle, an infirm 82 year-old, stumbled and rolled down the steps of the throne when he came forward to make his homage and had to be helped to his feet by the Queen. Later the Bishop of Bath and Wells turned over two pages in his Order of Service at once and told the Queen that the ceremony had finished and she should retire to St Edward the Confessor’s Chapel – she then had to be brought out again.

Lord Melbourne remarked that St Edward’s Chapel was “more unlike a Chapel than anything [I] have ever seen; for, what was called an Altar was covered with sandwiches, bottles of wine, etc.” (At the coronation of George VI, the late Queen’s father, many peers, clearly with tidier habits, arrived with sandwiches concealed in their coronets.)

The Archbishop of Canterbury then arrived to hand her the orb, only to discover she already had it.

Wearing the Crown of State, which she said later hurt her a great deal, Victoria then retired to the robing room and spent half an hour with her hand in a glass of iced water before they could get the ring off her swollen finger. (It can be seen in the portrait below.)

Despite it all Victoria wrote in her diary: “…I shall ever remember this day as the proudest of my life.”

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)