The British in India, from the 17th century onwards, cheerfully lumped the many and varied styles of cooking, and the subtle differences in dishes they encountered, under the term ‘curry’, a word copied from the Portuguese. Pietro della Valle (died 1652) described as ‘caril’ or ‘carre’ the ‘broths… made with Butter, the Pulp of Indian Nuts… and all sorts of Spices, particularly Cardamons and Ginger… besides herbs, fruits and a thousand other condiments [which are] poured in good quantity upon … boyl’d Rice.’

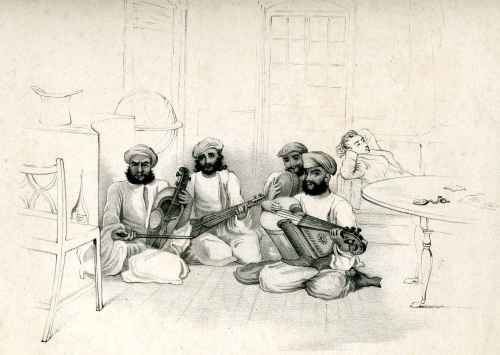

The British in India ate ‘curry’ with every meal, using the term to cover anything in a spicy sauce. No British lady would dream of undertaking her own cooking, so she would have no idea about how the dishes her Indian household served up were made. Eventually curry powder came to be considered a spice in its own right, completely ignoring the infinite varieties and combinations that might be used. Anglo-Indians might think they were immersing themselves in local culture – like the young East India Company employee above, listening to Indian musicians amongst his European furniture – but they seemed to have no appreciation of the subtleties of the cuisine.

As East India Company officials came back to Britain they brought their taste for curry with them and often they brought their Indian cooks with them. These men had learned to create the first Anglo-Indian cookery style to suit their employers and soon curry began to appear in ordinary household cookery books.

One enterprising India entrepreneur, Sake Dean Mahomed [Sidi Deen Mahomet in some sources], opened the first Indian restaurant in Britain in 1810. I discovered it (or, rather, where it had been) when I was researching for Walking Jane Austen’s London. It was located on the corner of George Street and Charles Street, just North of Portman Square, a fashionable area and one that was home to many retired Anglo-Indians. The Hindostanee Coffee House even had a smoking room where patrons could smoke hookahs. Despite serving ‘Indian dishes in the highest perfection… allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequaled to any…ever made in England’ the business became bankrupt the following year. Possibly his choice of location was unfortunate and many of the Anglo-Indians could eat curry at home made by their own Indian cooks or they preferred to combine business with curry by patronising the various City coffee houses that served curry alongside English food. Norris Street Coffee House on Haymarket had been serving curry since 1773 when its ‘Mistress’ advertised in The Public Advertiser ‘true Indian curey paste.’ ‘At the shortest Notice [she would send] ready dressed Curey and Rice, also Indian Pilaws, to any Part of the Town.’ East India Company merchants had created almost a club for themselves at the Jerusalem Coffee House on Cornhill. No specialist Indian restaurant appeared again in Central London until the 1920s.

Sake Dean Mahomed (right. Painted by Thomas Mann Baines c.1810) had far more success with his bathing establishment in Brighton. “Mahomed’s Baths. These are ascertained [sic] by a native of India, and combine all the luxuries of oriental bathing. They are adapted either for ladies or gentlemen, and the system is highly salutary in many diseases, independently of the gratification it affords, particularly to those who have resided in the East.” [W. Scott. The House Book or Family Chronicle of Useful Knowledge (1826)] The ‘luxuries of oriental bathing’, I learned when I was researching for The Georgian Seaside, included shampooing – not of the head, but of the whole body in a foaming massage.

The Epicure’s Almanac (1815) has a section on seasonal foods and for July mentions that ‘various preparations of curry afford a delectable repast to those who have acquired a taste for this Indian diet.’ Ready-made curry powder could be bought alongside other spices and was first mentioned in Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery (1747).

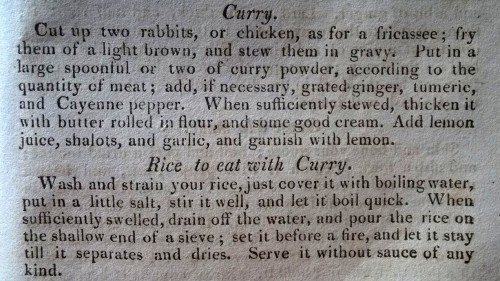

Here is a recipe for curry made with curry powder from The New London Family Cook (1811) by Duncan McDonald, head cook at the Bedford Tavern and Hotel, Covent Garden. The Bedford Tavern and Hotel was a large establishment on the Great Piazza. It opened in 1726 and continued in business throughout most of the 19th century.

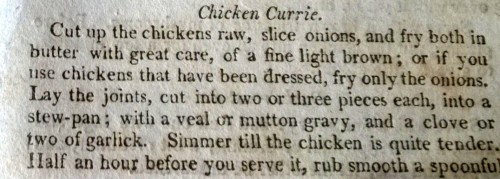

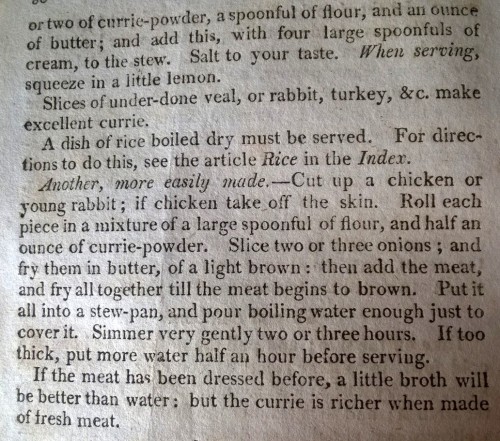

And this is from A New System of Domestic Cookery (1807)

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005).

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005).

It’s all fascinating stuff. You do wonder what the ‘curry powder’ consisted of. Also, where the imported Indian cooks found their ingredients

Pingback: The Story of a Square 10: Portman Square | Jane Austen's London