After exhaustive (and exhausting) sightseeing on Monday and Tuesday, described in my previous two posts, Mr Whittock (The Modern Picture of London, 1836) has a far shorter list of places to visit for Wednesday. I suspect it would not be much less demanding.

He begins by instructing the tourist to Visit the Adelaide Gallery in Adelaide Street. This was a new street at the time Mr Whittock was writing and was part of the redevelopment of the area that is now Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery and which was the King’s and Queen’s Mews and the St Martin’s Workhouse, the Golden Cross Inn, the Phoenix Insurance company’s fire station and assorted small dwellings and workshops.

The site was cleared in 1830 but work on the hard landscaping of the Square did not begin until 1840. Those visitors guided by Mr Whittock would have seen a vast building site.

Adelaide Street runs from the Strand northwards behind St Martin in the Fields church (seen in the image of 1815). The Adelaide Gallery of Science and Art was one of the most interesting and rational exhibitions in London… and contains models of the most curious discoveries in mechanics, engineering etc. Perkin’s celebrated steam gun, the modern diving bell, the model of the process of distillation from bread and hundreds of other curiosities are exhibited here. The rooms are open daily, the admission is one shilling, and it is impossible to spend a shilling at any other exhibition in London where so much amusement and information may be gained.

Jacob Perkins, an American, patented his steam gun in 1824 and tests showed that it could fire projectiles at great pressure and could even work as a machine gun. The Duke of Wellington became interested, so did the French, the Russians and the Turks. It all came to nothing in the end in a quagmire of government indecision about spending, prejudice against ‘colonials’ and the improvement of more conventional weapons.

The London Mechanics’ Register in November 1824 wrote, If Mr. Perkins’s steam guns were introduced into general use, there would be but very short wars; since no fecundity could provide population for its attacks…What plague, what pestilence would exceed, in its effects, those of the steam gun? – 500 balls fired every minute…one out of 20 to reach its mark – why, 10 such guns would destroy 150,000 daily. If we did not feel that this mode of warfare would end in producing peace, we should be far from recommending it…We have heard, but we do not vouch for the fact, that the Emperor of Russia, who has more knowledge of the importance of steam than some of us Englishmen, has sent an agent to procure a supply of Perkins’s steam guns, which that gentleman’s patriotism will not allow him to offer…

As for distillation from bread – Googling the term produces some interesting results, including vodka from stale bread crusts!

From there we proceed to the British Museum

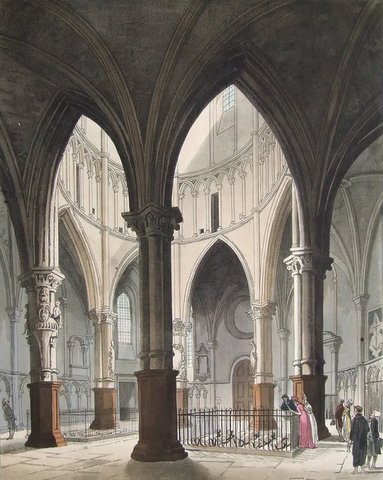

This was the beginning of the building we see today, although work had only begun in 1823 on a replacement for Montague House, the building purchased on the site in 1755. Visitors had to negotiate a vast building site, but much of the original remained at the time Whittock was writing, including the entrance gates on Great Russell Street. He does not say how long to allow to see the collections – which occupy ten pages in his guidebook. To secure admission it was necessary to enter one’s name and details of one’s companions in a ledger and to leave one’s walking stick, umbrella etc at the entrance. Apparently all visitors, provided they conducted themselves ‘with propriety’, were treated as equal, from noblemen to artisans, sailors and mechanics. The print of 1810 shows a new gallery to house Classical works.

Next Ride to the Regent’s Park –

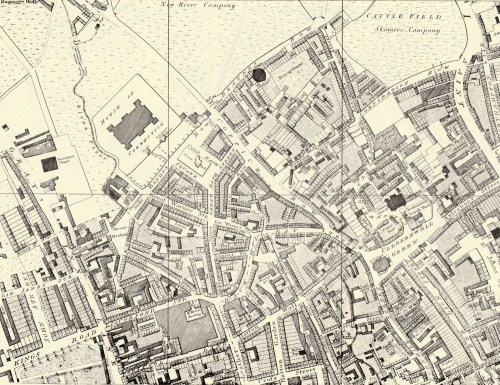

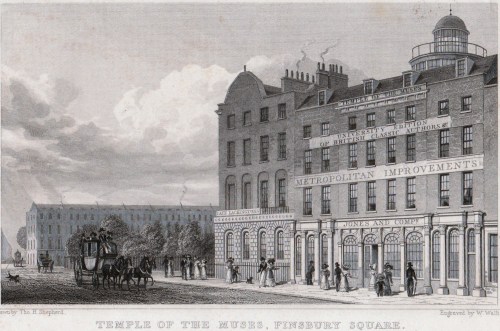

Regent’s Park was originally an area of about 500 acres of royal hunting land which had become farms. The leases on the farms came due in 1811 and a scheme was formed to create a vast public park and terraces of superior houses to be linked by a new street to Westminster. John Nash was the architect chosen and he received the enthusiastic support of the Prince Regent despite endless opposition, quibbles and delays. In 1820 work began on the terraces and on the first of eight villas. (The one shown below in a print of 18128 belonged to Thomas Raikes, dandy and diarist.) In 1828 the Zoological Society of London’s zoo was opened on the northern edge of the park and the gardens of the Royal Botanical Society occupied the centre (until 1932). The majority of the park was open to the public by 1841. The plan above is from Metropolitan Improvements with drawings by Thomas Shepherd (1827)

see the Diorama –

The Regent’s Park diorama was run by Jaques Daguerre, photographic pioneer, and was opened in 1823. The entrance was in the facade of 9-10, Park Square East and the interior was a circular auditorium seating two hundred which could be moved through 73 degrees by a boy operating a ram engine so that two stages could be used and the scenes changed to reveal different tableaux. The main images were painted on vast rollers – 22 metres long by 12 metres high – and various props, shutters, light and sound effects added. One of the most popular was A Midnight Mass of St Etienne-du-Mont. The scene changed from daylight to candlelight, the congregation gradually appeared, midnight mass began and the organ was played. Then, gradually the congregation leaves and daylight returns.

the Coliseum –

This was at the Cambridge Gate of the park, and was designed by Decimus Burton. Despite its name it looked more looked like the Pantheon in Rome. At first the views of London which had been sketched by Mr Horner from the very top of St Paul’s Cathedral and turned into a large panorama, seventy feet tall, were very popular, but interest flagged and it was demolished in 1875. Visitors climbed staircases inside to reach the apparent height of the external gallery around the top of the dome of St Paul’s. Admission was one shilling and, for an extra six pence one could ascend by means of a moving compartment, which is a small circular room, in which six or eight persons are comfortably seated, and raised by machinery. The first elevator?

Swiss Cottage, &c. –

I have not been able to find information about the Swiss Cottage in the Park which appears to have no connection to the modern Swiss Cottage pub and area. There was a fad for ornamental buildings in this style and perhaps this was a refreshment place.

Return home down Regent Street

It was key for the success of the Regent’s Park development that it could be easily connected to what was fashionable central London at the time and the route chosen had the advantage of improving the rather squalid areas around Haymarket and Pall Mall while sorting out traffic congestion around the Strand and Charing Cross. In his words Nash’s proposal for the route will be a boundary and complete separation between the Streets and Squares occupied by the Nobility and Gentry, and the narrower Streets and meaner houses occupied by mechanics and the trading part of the community.

The section between Piccadilly and Oxford Street was devoted to shopping and was known as the Quadrant (shown above in 1822 and rebuilt in the 1920s). Lower Regent Street, between Piccadilly and St James’s Park was to be semi-residential with clubs such as the Atheneum and the section north of Oxford Street was mainly residential.

– dine, and in the evening visit Astley’s Amphitheatre.

Astley’s Amphitheatre was in Westminster Bridge Road. Originally a canvas structure built by Philip Astley in 1768 it was rebuilt twice by the time Mr Whittock’s tourists visited, it would burn down again and be rebuilt in 1841 and 1862. It was finally demolished in 1893.

Astley’s was a very popular, low-brow form of entertainment with strong elements of the circus. Equestrian performers were a very important part of the shows but clowns (including Grimaldi), acrobats and tightrope acts performed and shows included melodramas, tableaus and dramatic sword fights. You can read more about it in this post. Jane Austen visited and enjoyed it and sent Harriet Smith and Robert Martin to visit in Emma.

The weary tourist can now stagger back to his lodgings and prepare for the next day when a variety of transport awaits him – omnibus, ferry, railroad (!) and hackney carriage.

This 1811 image is of the interior courts of the Bank, designed by Sir John Soane. Now only his massive exterior wall remains and the interior has been completely rebuilt.

This 1811 image is of the interior courts of the Bank, designed by Sir John Soane. Now only his massive exterior wall remains and the interior has been completely rebuilt.

Passing through St. Margaret’s church-yard (Above: Westminster Abbey with St Margaret’s church in front, seen from the north (1810)), he will observe the beautiful entrance to the north transept of the Abbey. The next object that will present itself, is the chapel of Henry VII., and he will arrive at Poet’s Corner at about half-past ten o’clock: the entrance to the Abbey will be open, and he will have an opportunity of hearing the cathedral service performed, and likewise of seeing the beautiful choir of the Abbey; the service is ended about eleven o’clock, and he can then survey every part of this venerable pile, which will occupy about an hour.

Passing through St. Margaret’s church-yard (Above: Westminster Abbey with St Margaret’s church in front, seen from the north (1810)), he will observe the beautiful entrance to the north transept of the Abbey. The next object that will present itself, is the chapel of Henry VII., and he will arrive at Poet’s Corner at about half-past ten o’clock: the entrance to the Abbey will be open, and he will have an opportunity of hearing the cathedral service performed, and likewise of seeing the beautiful choir of the Abbey; the service is ended about eleven o’clock, and he can then survey every part of this venerable pile, which will occupy about an hour.

This image of 1784 shows Morton’s Tower, the entrance to the Palace with Westminster bridge (opened 1750) in the background. The tower is instantly recognizable today, even though the embankment has been built up between it and the river and the traffic now thunders past on Lambeth Palace Road.

This image of 1784 shows Morton’s Tower, the entrance to the Palace with Westminster bridge (opened 1750) in the background. The tower is instantly recognizable today, even though the embankment has been built up between it and the river and the traffic now thunders past on Lambeth Palace Road.

In 1753 there was the first use of the term “bathing machine”. This was applied to the improved version devised by Benjamin Beale at Margate. This had a canvas hood on hoops that could be let down on the seaward side of the machine allowing bathers a private space to swim unobserved. One can be seen billowing like a cloud from the machine depicted on a souvenir flask.

In 1753 there was the first use of the term “bathing machine”. This was applied to the improved version devised by Benjamin Beale at Margate. This had a canvas hood on hoops that could be let down on the seaward side of the machine allowing bathers a private space to swim unobserved. One can be seen billowing like a cloud from the machine depicted on a souvenir flask.

These are at Bexhill on Sea in 1919.

These are at Bexhill on Sea in 1919.

Certainly, the London Encyclopedia records no interesting inhabitants until the middle of the 19th century, although the staircase of number 20 was the location of the cover shoot for the Beatles’ Please Please Me.

Certainly, the London Encyclopedia records no interesting inhabitants until the middle of the 19th century, although the staircase of number 20 was the location of the cover shoot for the Beatles’ Please Please Me.

“The edifice, which is of brick, stands within a large area, encompassed by a strong buttressed wall of moderate height. The gate is of Portland stone, contrived in a massy style, and sculptured with fetters, the hateful but necessary appendages of guilt.”

“The edifice, which is of brick, stands within a large area, encompassed by a strong buttressed wall of moderate height. The gate is of Portland stone, contrived in a massy style, and sculptured with fetters, the hateful but necessary appendages of guilt.”

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)