It’s Thursday, the fourth day of the London sightseeing programme proposed by Nathaniel Whittock in 1836. By now the tourists are either on their knees with exhaustion or getting their second wind after the itineraries described in my previous three posts. They might be relieved to find that there is a fair amount of riding around involved in today’s expedition. This itinerary illustrates more clearly than any of the others how close to the Victorian era these visitors are as they experience engineering marvels and improvements in public transport.

Get into the omnibus or coach that goes to Blackwall.

Mr Whittock informs us that “Omnibusses [sic] now run through the leading thoroughfares: their charge is generally stated on the outside of the carriage. At the present time it is as cheap as the most rigid economist could desire as a person may ride in a handsome vehicle from the Bank to Paddington, a distance of four miles, for sixpence.”

George Shillibeer brought horse-drawn omnibuses (shown in the print above) to London in 1829, having seen them operating in Paris. At first they operated with a conductor who took the fares but did not issue tickets. He recorded all the transactions on a waybill, then paid his own, and the driver’s, wages from the money collected and handed the rest over to the bus owner.

An account of the new service was given in the Morning Post of 7 July 1829. “Saturday the new vehicle, called the Omnibus, commenced running from Paddington to the City, and excited considerable notice, both from the novel form of the carriage, and the elegance with which it is fitted out. It is capable of accommodating 16 or 18 persons, all inside, and we apprehend it would be almost impossible to make it overturn, owing to the great width of the carriage. It was drawn by three beautiful bays abreast, after the French fashion. The Omnibus is a handsome machine, in the shape of a van. The width the horses occupy will render the vehicle rather inconvenient to be turned or driven through some of the streets of London.”

see the East and West India Docks

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.

The map shows the docks in 1849.

A short walk thence will take you to the Ferry-House. On crossing the Thames, see Greenwich Hospital.

These days an entire day can easily be spent in Greenwich but Mr Whittock merely invites his readers to admire the exterior of the buildings (he doesn’t even mention the Queen’s House), enter the Great Hall and look up the hill to the Observatory – ‘a conspicuous and celebrated Object.’

Ride on the Railroad as far as Bermondsey;

This would have been a real highlight for visitors – the first railway line in London. It was intended only for passengers and was built from London Bridge to Greenwich on a viaduct twenty two feet above the ground and supported on “nearly a thousand arches…intended to be converted into dwelling-houses or places of business.” It cut the journey time from London Bridge to Greenwich from an hour to ten minutes and was the forerunner of all the London commuter lines.

walk to Rotherhithe, devote an hour to the examination of the Tunnel.

Interestingly, Mr Whittock seems more excited about the Thames Tunnel than he does about the railway. It was certainly an epic piece of engineering, during the course of which Marc Brunel (father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel) invented the tunnel shield which is the basis of all tunnel-boring today. Made essential by the development of the docks, and the problems of building bridges over the Thames to bring the workers from south of the river, it was intended for carriage traffic but instead became a footway and a major tourist attraction. It was converted to take the East London railway line in 1869. The print is from 1835.

Dine at Rotherhithe, and afterwards ride to the Surrey Zoological Gardens.

The Surrey Zoological Society Gardens were founded in 1831 and occupied a site now under Penton Place in Walworth, just north-east of the Oval cricket ground. Impressario Edward Cross sold them the contents of his menagerie at Exeter Change which I blogged about here. It must have been some improvement for the animals who were housed in cages under a circular domed glass conservatory 300 feet (90 m) in circumference. There were lions, tigers, a rhinoceros and giraffes (shown here in 1841) and, for a time, the gardens were more popular than London Zoo in Regent’s Park. However, that was subsidised, and cheaper (the Surrey Gardens cost one shilling admission), so gained in popularity. The gardens, which were lavishly planted and dotted with pavilions, were used for large public entertainments from 1837 – re-enactments of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the Great Fire of London, or the storming of Badajoz – and spectacular firework displays. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was the final nail in its coffin and it closed in 1856.

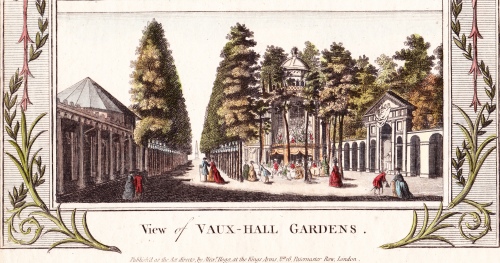

Towards the evening return to dress, and at eight o’clock go by water to Vauxhall.

Vauxhall Gardens lay where the modern park is still situated, close to the Thames and Vauxhall Bridge. Going by water was the traditional way of visiting, even though the first bridge had opened in 1816.

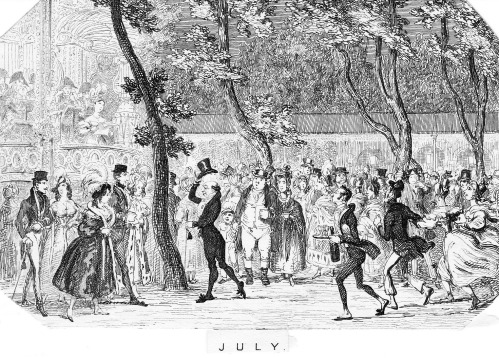

I have blogged about Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens here and also in comparison with their rival, Ranelagh. The print by Cruickshank shows the Gardens in the 1830s, just as our tourists must have seen them.

They would have staggered back to their lodgings late and perhaps a trifle tipsy. Hopefully they get a decent night’s sleep, because Friday will be devoted to the West End, London Zoo, shopping and the theatre.

If you are interested in more of the slang used for London’s criminal classes, including the river thieves, you can find that, and much more, here