In April 1811 Jane Austen was staying with her brother Henry and his wife Eliza at their home 64, Sloane Street and working on the proofs of Sense and Sensibility. Not that this prevented her from getting out and about in London and occasionally borrowing Henry’s carriage: ‘The Driving about, the Carriage being open, was very pleasant. I liked my solitary elegance very much, & was ready to laugh all the time, at my being where I was – I could not but feel that I had naturally small right to be parading about London in a Barouche,’ she wrote on a later visit.

But delightful as travel by coach might be, horse-drawn vehicles were dangerous and accidents were numerous, even if most were minor. In a letter home on 25 April 1811 Jane blames an inci dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in Walking Jane Austen’s London.

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in Walking Jane Austen’s London.

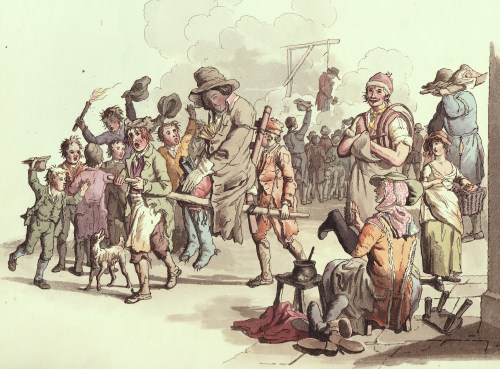

The wonderful Henry Alken snr. excelled at drawing horses, but he had a mischievous side and produced numerous prints of carriage accidents. [His Return From the Races is at the top of this post]. These are light-hearted, often mocking the young sporting gentlemen of his day and their ‘boy-racer’ equipages, but the potential for an accident to cause death or serious injury was very real. In one hideous stage coach crash in 1833 the Quicksilver coach overturned as it was leaving Brighton. Passengers were flung out into the gardens along the Steine and impaled on the spiked railings. Alken’s third plate in his Trip to Brighton series shows a stagecoach crash as a result of young bucks bribing the coachmen to let them take the reins and race. Discover more of the dangers of travel by stage or mail coach in Stagecoach Travel.

Alken’s ‘comic’ drawings show people thrown onto the rough stones of the road, against milestones or walls, at risk of trampling by the horses or of being injured by the splintering wood and sharp metal fittings of their carriages. One has to assume that like cartoon characters walking off a cliff they all bounce back safely with only their dignity ruffled. Real life would not have been so forgiving. In this post I am sharing some of the Alken carriage disasters from my own collection.

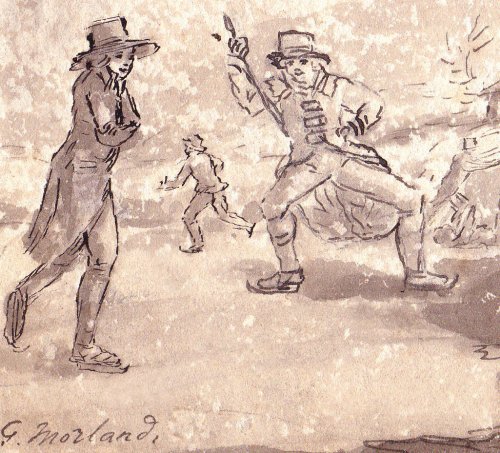

In Learning to Drive Tandem (1825)  Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

One of my favourite images is this one of a Dennet gig with the horses spooked by a passing stagecoach. The passengers’ faces as they watch the driver struggling with his team are priceless.

Several prints of the time show accidents at toll gates. Either the horses bolted or the driver wasn’t paying attention or perhaps they thought the gate keeper would fling the gate wide as they approached. This one is captioned “I wonder whether he is a good jumper!”

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.  In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.

In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.

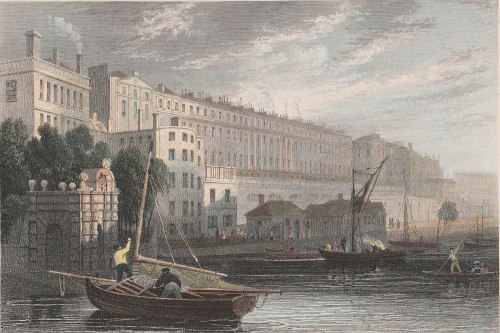

Captain Bull’s packet ship, the Duke of Malborough (see below), did fight in 1814 off Cape Finistere against a privateer. Sadly, one passenger was a casualty. Even more sadly, it transpired that the attacking ship was not a privateer at all, but a ship of the Royal Navy! They do indeed call it the fog of war.

Captain Bull’s packet ship, the Duke of Malborough (see below), did fight in 1814 off Cape Finistere against a privateer. Sadly, one passenger was a casualty. Even more sadly, it transpired that the attacking ship was not a privateer at all, but a ship of the Royal Navy! They do indeed call it the fog of war.

After many years publishing Regencies with Harlequin Mills & Boon, Joanna is very excited about branching out into new fields as an independent author with

After many years publishing Regencies with Harlequin Mills & Boon, Joanna is very excited about branching out into new fields as an independent author with  her second book will be a timeslip, Lady In Lace. Details of all her books are at

her second book will be a timeslip, Lady In Lace. Details of all her books are at