The New Family Cookery or Town and Country Housekeepers’ Guide by Duncan MacDonald (1812) begins its General Directions for Marketing with fish and with Billingsgate Market:

The comment in the penultimate paragraph is ironic, considering Billingsgate’s colourful reputation! When I was researching for my book Regency Slang Revealed I discovered that to talk Billingsgate meant to use particularly coarse and foul language.

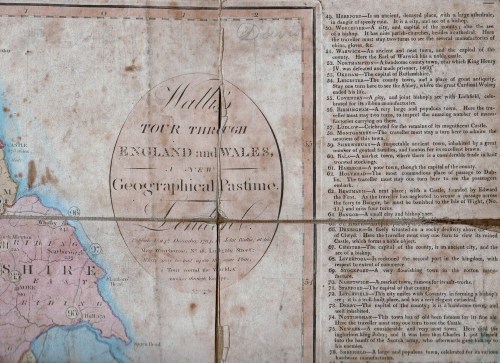

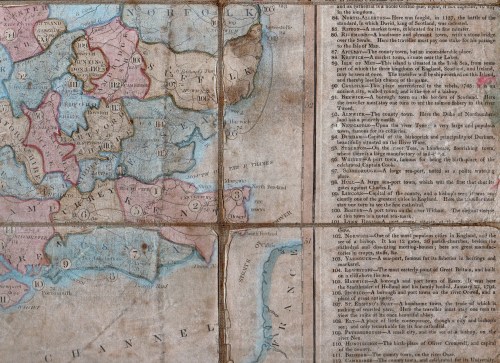

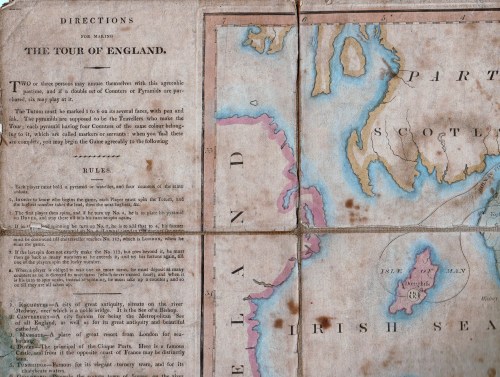

Billingsgate Market was sited at the foot of Lower Thames Street from at least the 10th century until it was moved to the new market site on the Isle of Dogs in 1982. The first set of toll regulations covering it dates from 1016 and by the time of Elizabeth I it was dealing in corn, malt, salt and vegetables, although fish was always the main reason for its existence at the highest point where fish could be unloaded straight from the boats before London Bridge. It can be seen in Horwood’s map of London (c1800) below with the deep indentation of the dock taking a bite out of the waterfront and London Bridge on the left. This dock vanished with the Victorian rebuilding of the market in 1850. That building proved inadequate and was replaced with the present handsome structure by Sir Horace Jones, opened in 1877. It was refurbished after the closure and is now used for various commercial purposes. During the 1988 work extensive remains of the late 12th century/early 13th century waterfront were revealed.

The engraving from a print of 1820 shows the view of the dock from the river. At this date there was no covered market building, simply stalls and tables set out around the dock. In the days before a ready supply of ice dealers would come into Billingsgate from places within about twenty five miles – an outer ring that included Windsor, St Albans and Romford – and fish was sold in lots by the Dutch auction method where the price falls until a buyer is found.  Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.

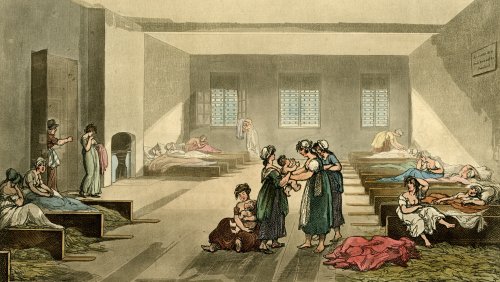

It was the fishwives of Billingsgate who became its most notorious feature. They were tough women, as they needed to be to thrive in such a hard, competitive business, and they did not shrink from either physical violence or colourful language. In Bailey’s English Dictionary (1736) a “Billingsgate” is defined as “a scolding, impudent slut.” Addison referred to the “debate” that arose among “the ladies of the British fishery” and Ned Ward describes them scolding and chattering among their heaps of fish, “ready enough to knock down the auctioneer who did not knock down a lot to them.”

The women of Billingsgate were an inevitable attraction to young bucks and gentlemen slumming, as the two prints below show. The top one is a drawing by Henry Alken for the Tom and Jerry series – “Billingsgate: Tom and Bob taking a Survey after a Night’s Spree.” Below that is “A Frolic: High Life or a Visit to Billingsgate” from The London Spy.

Here two sporting gentlemen stand out in the crowd of working people as they watch a fight that has broken out between two bare-breasted fishwives. Another has just been knocked to the ground. Amongst the details note the woman sitting on a basket smoking a clay pipe, another (far left) taking a swig from a bottle and the porter’s hat on the man in the centre foreground with its long ‘skirt’ to protect the neck.

This print below is not dated, but as there is the funnel of a steam boat in the background amongst the masts it is probably 1820s.

Here a determined-looking lady in a riding habit, her veil thrown back and her whip under her arm, is negotiating the sale of a large fish head. Behind her is a smartly-dressed woman, perhaps a merchant’s wife, and an elderly gentleman in spectacles is talking to another fish seller on the far right. There are two men in livery, perhaps accompanying the lady in the riding habit. The man standing behind the seated fishwife is a sailor, judging by his tarred pigtail, and the porter walking towards us is wearing one of the black hats whose ‘tail’ can just be glimpsed over his shoulders. It is all fairly orderly and respectable, despite the crowd (and the smell, no doubt) but a hint to the other activities in the area may be the couple in the window!

Whether you picked your bay leaves, sent a card or received a delightful verse – happy Valentine’s Day!

Whether you picked your bay leaves, sent a card or received a delightful verse – happy Valentine’s Day!