It’s Thursday, the fourth day of the London sightseeing programme proposed by Nathaniel Whittock in 1836. By now the tourists are either on their knees with exhaustion or getting their second wind after the itineraries described in my previous three posts. They might be relieved to find that there is a fair amount of riding around involved in today’s expedition. This itinerary illustrates more clearly than any of the others how close to the Victorian era these visitors are as they experience engineering marvels and improvements in public transport.

Get into the omnibus or coach that goes to Blackwall.

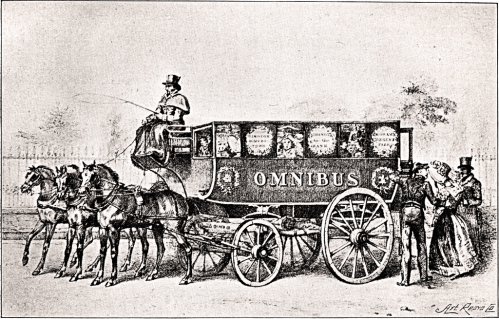

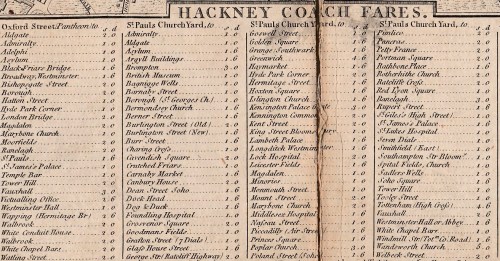

Mr Whittock informs us that “Omnibusses [sic] now run through the leading thoroughfares: their charge is generally stated on the outside of the carriage. At the present time it is as cheap as the most rigid economist could desire as a person may ride in a handsome vehicle from the Bank to Paddington, a distance of four miles, for sixpence.”

George Shillibeer brought horse-drawn omnibuses (shown in the print above) to London in 1829, having seen them operating in Paris. At first they operated with a conductor who took the fares but did not issue tickets. He recorded all the transactions on a waybill, then paid his own, and the driver’s, wages from the money collected and handed the rest over to the bus owner.

An account of the new service was given in the Morning Post of 7 July 1829. “Saturday the new vehicle, called the Omnibus, commenced running from Paddington to the City, and excited considerable notice, both from the novel form of the carriage, and the elegance with which it is fitted out. It is capable of accommodating 16 or 18 persons, all inside, and we apprehend it would be almost impossible to make it overturn, owing to the great width of the carriage. It was drawn by three beautiful bays abreast, after the French fashion. The Omnibus is a handsome machine, in the shape of a van. The width the horses occupy will render the vehicle rather inconvenient to be turned or driven through some of the streets of London.”

see the East and West India Docks

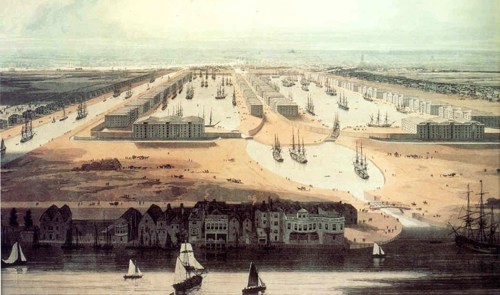

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.

The London docks must have been a spectacular sight, teeming with a mass of sailing ships from all parts of the world. The print is a detail from a painting of 1802, looking west across the neck of the Isle of Dogs towards the City, and showing the West India Dock, opened that year. The import dock is on the right, the dock on the left is for export. The canal on the left later became the South Dock. The East India Docks were slightly to the east at the top of the northward bend of the Blackwall Reach of the Thames. Surrounding the docks were huge secure warehouses with walls thirty feet high and their own guards, an effective protection against the menace of ‘limpers’, ‘water pads’ and ‘water sneaks’ who preyed on the craft moored in the river itself.

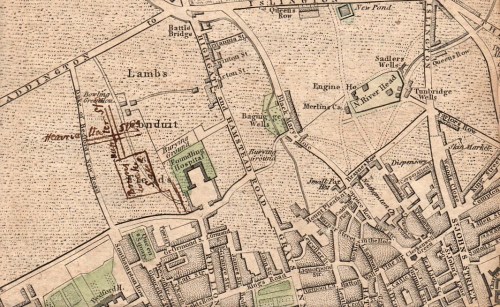

The map shows the docks in 1849.

A short walk thence will take you to the Ferry-House. On crossing the Thames, see Greenwich Hospital.

These days an entire day can easily be spent in Greenwich but Mr Whittock merely invites his readers to admire the exterior of the buildings (he doesn’t even mention the Queen’s House), enter the Great Hall and look up the hill to the Observatory – ‘a conspicuous and celebrated Object.’

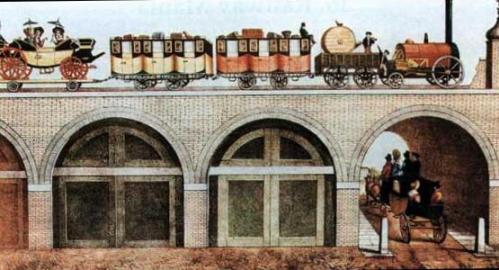

Ride on the Railroad as far as Bermondsey;

This would have been a real highlight for visitors – the first railway line in London. It was intended only for passengers and was built from London Bridge to Greenwich on a viaduct twenty two feet above the ground and supported on “nearly a thousand arches…intended to be converted into dwelling-houses or places of business.” It cut the journey time from London Bridge to Greenwich from an hour to ten minutes and was the forerunner of all the London commuter lines.

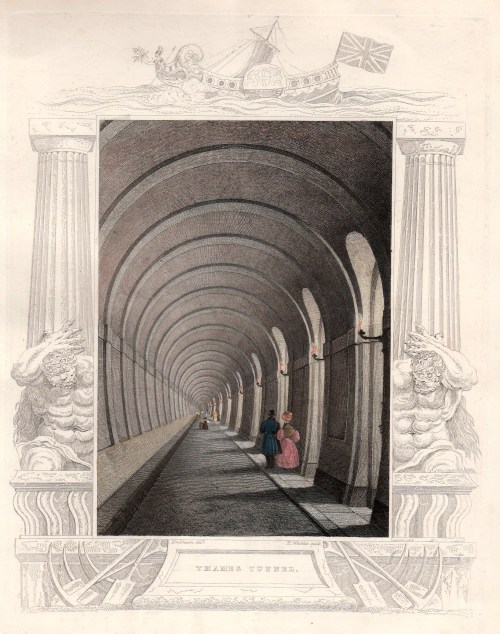

walk to Rotherhithe, devote an hour to the examination of the Tunnel.

Interestingly, Mr Whittock seems more excited about the Thames Tunnel than he does about the railway. It was certainly an epic piece of engineering, during the course of which Marc Brunel (father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel) invented the tunnel shield which is the basis of all tunnel-boring today. Made essential by the development of the docks, and the problems of building bridges over the Thames to bring the workers from south of the river, it was intended for carriage traffic but instead became a footway and a major tourist attraction. It was converted to take the East London railway line in 1869. The print is from 1835.

Dine at Rotherhithe, and afterwards ride to the Surrey Zoological Gardens.

The Surrey Zoological Society Gardens were founded in 1831 and occupied a site now under Penton Place in Walworth, just north-east of the Oval cricket ground. Impressario Edward Cross sold them the contents of his menagerie at Exeter Change which I blogged about here. It must have been some improvement for the animals who were housed in cages under a circular domed glass conservatory 300 feet (90 m) in circumference. There were lions, tigers, a rhinoceros and giraffes (shown here in 1841) and, for a time, the gardens were more popular than London Zoo in Regent’s Park. However, that was subsidised, and cheaper (the Surrey Gardens cost one shilling admission), so gained in popularity. The gardens, which were lavishly planted and dotted with pavilions, were used for large public entertainments from 1837 – re-enactments of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the Great Fire of London, or the storming of Badajoz – and spectacular firework displays. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was the final nail in its coffin and it closed in 1856.

Towards the evening return to dress, and at eight o’clock go by water to Vauxhall.

Vauxhall Gardens lay where the modern park is still situated, close to the Thames and Vauxhall Bridge. Going by water was the traditional way of visiting, even though the first bridge had opened in 1816.

I have blogged about Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens here and also in comparison with their rival, Ranelagh. The print by Cruickshank shows the Gardens in the 1830s, just as our tourists must have seen them.

They would have staggered back to their lodgings late and perhaps a trifle tipsy. Hopefully they get a decent night’s sleep, because Friday will be devoted to the West End, London Zoo, shopping and the theatre.

If you are interested in more of the slang used for London’s criminal classes, including the river thieves, you can find that, and much more, here

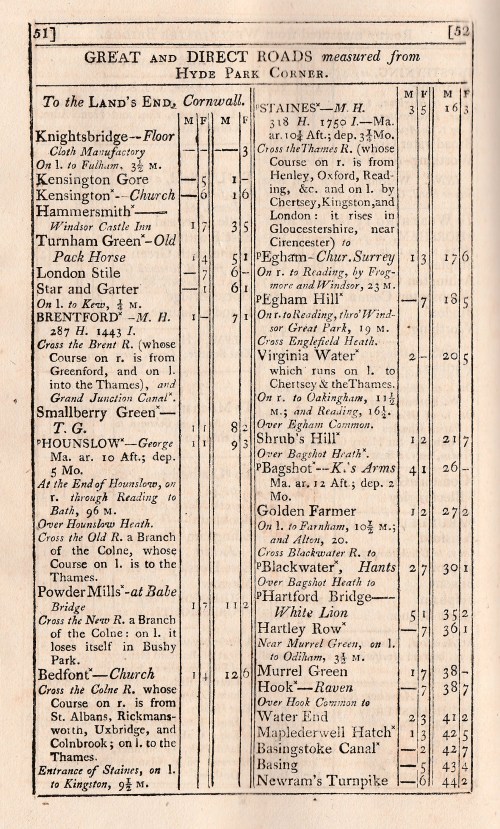

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

The first footman, two more footmen, two maids (more of those can be hired locally along with assorted kitchen skivvies) and Gaston the chef, left three days before to set up the house on the Esplanade and hire extra staff and furnishings required. That involved two lumbering old coaches plus a baggage coach.

The first footman, two more footmen, two maids (more of those can be hired locally along with assorted kitchen skivvies) and Gaston the chef, left three days before to set up the house on the Esplanade and hire extra staff and furnishings required. That involved two lumbering old coaches plus a baggage coach.

building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.

building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

dent at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng. air several minutes.’ You can follow Jane’s London travels in

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Alken shows a young gentleman who has got one of his pair turned around and one wheel off the road. The vehicle is a cocking cart used to transport fighting cocks and below the seat is a compartment ventilated by slats and a small image of a fighting cock on the armrest. In The Remains of a Stanhope (1827) the crash has already occurred, showing just how fragile these vehicles could be. A carpenter has been summoned and the owner is drawling somewhat optimistically, “I say my clever feller, have you an idea you can make this thing capable of progression?”

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.

Young men crashing their vehicles was obviously commonplace, and then as now, showing off to the ladies was also part of the joy of owning a sporting vehicle. Alken was not above titillating his audience with a glimpse of petticoat or a shapely leg, even when the owner of the leg was about to get seriously hurt. In “Up and down or the endeavour to discover which way your Horse is inclined to come down backwards or forwards” (1817) the driver takes no notice at all of his fair passenger vanishing over the back of his fancy carriage. There are some nice details in this print – the two-headed goose on the side panel is presumably a reference to the driver not knowing which way he is going and the luxurious sheepskin foot rug is clearly visible.  In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.

In the same series is an awful warning about the dangers of not choosing your horses with care. Captioned “Trying a new match you discover that they are not only alike in colour weight & action but in disposition.” One young man is heading out over the back of the carriage while his companion is poised to leap for safety amidst flying greatcoats, hats and seat cushions.