“FIVES-COURT. A place distinguished (in addition to the game of fives) for sparring matches between the pugilists. The combatants belonging to the prize-ring exhibit the art of self-defence at the Fives-Court with the gloves; and it is frequently at this Court where public challenges are given and accepted by the boxers. The most refined and fastidious person may attend these exhibitions of sparring with pleasure; as they are conducted with all the neatness, elegance and science of FENCING. Admission, 3s. each person. It is situated in St. Martin’s Street, Leicester-fields.”

(Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, revised and corrected…by Pierce Egan. 1823)

I was comparing the first, 1785, edition of Francis Grose’s Vulgar Tongue with the 1823 edition edited by that aficionado of ‘Boxiana’, pioneer sporting journalist and creator of Tom and Jerry, Pierce Egan, when I came across this reference to the Fives Court, obviously added by Egan.

The print at the top of this post is from my collection and I had wondered where the Fives Court was located – it was obviously a very large structure, judging from the light streaming in from a high window. It was built as a court for the game of fives, a sort of hand-ball, or hand-tennis, originally thought to have been played against church buttresses, but then adopted at the public schools of Rugby and Eton and refined. Like Real (Royal) tennis it is played on an indoor court with high walls and various slopes and ledges.

In 1802 a sparring exhibition was held between Mendoza and Bill Warr – two boxing superstars. It was held on the floor of the court, not on a removable platform ring as shown in my much later (1823) print, that was introduced at the suggestion of black pugilist Bill Richmond.

Initially the admission was two shillings or two and six pence up to three and six, but, as Grose states, it was soon standardised at three shillings. Vincent Dowling, another sports writer, noted that there was a small dressing room at one end that had a window looking down on the Court and this was set aside for “…some dozens of noblemen and persons of high rank, whose liberal contributions (many of them giving a guinea for a ticket) added greatly to the receipts of the beneficiary.”

The quote reminds us that most of these exhibition bouts were benefit performances for one of the pugilists who would stand at the door with a collecting box soliciting further donations in advance of the bout. Bill Richmond (shown above, left), like many retired pugilists, owned a pub. His was the Horse and Dolphin, located strategically next to the Fives Court, and tickets for bouts were sold there as well as in other sporting taverns.

The Court could accommodate an audience of up to 1,000 and, if full, admission might raise £200. The chief beneficiary would have to pay a fee for the court and to the referee and Master of Ceremonies. Lesser fighters, who would appear earlier on in the programme as warm-up acts, also got a payment from the takings. The great ‘Gentleman’ Jackson controlled who could have bouts at the Court and appears to have done so with few complaints, although in 1821 he refused the application of his bitter rival, Mendoza.

The bouts were for exhibition purposes, which is why gloves were worn, and Richmond was the first to strip to the waist, sparring without vest or shirt, so that his musculature could be admired by the fans. This display attracted artists including Benjamin Haydon, Joseph Farington (President of the Royal Academy) and John Rossi the sculptor who ‘much admired Dutch Sam’s [shown above, right] figure on account of the symmetry and the parts being expressed.’

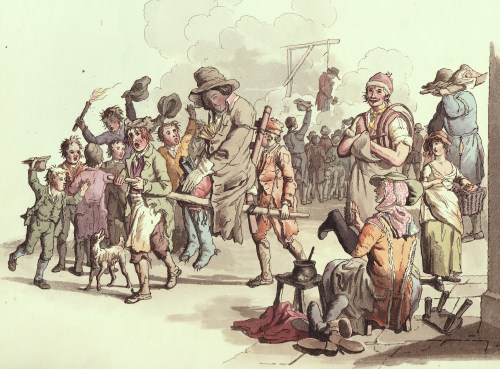

The 1823 print at the top of the post, ‘ “A Set-to” at the Fives-Court for the benefit of “One of the Fancy”’ is by Samuel Alken. The crowd is orderly and the gentlemen to either side in the foreground are very fashionably dressed. Respectably-dressed tradesmen can also be seen – one in an apron is in the audience sitting up on the right. The central figure facing us wears an apron and his arms are full of what look like giant cream horns. Close inspection shows that the contents are within conical containers stitched up the side – my guess is that these are some kind of bread roll, perhaps with a filling. I’d love to hear any other suggestions.

The Fives-Court operated as a boxing venue from 1802 until it closed in 1826 and was demolished as part of the redevelopment of the Royal Mews area into what became Trafalgar Square. The site is now under the northern edge of the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery and it is possible to pass this rather dreary location without the slightest inkling that it was once one of the sporting hot-spots of London. It is marked on the map in red.