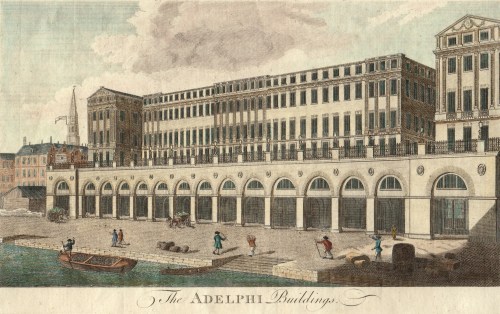

In the 1750s the three acre site between the Strand and the Thames that had once been occupied by Durham House was nothing more than a ruinous network of slum courts. It was to be transformed into the Adelphi (from the Greek for brothers), an elegant housing development, by the family of Scottish architects John, William, Robert and James Adam. They leased the land for 99 years and imported a large team of bagpipe-playing Scottish labourers – cheaper apparently than the local workmen and a source of considerable resentment. (although the unfamiliar bagpipes may have contributed to that).

The Thames was not embanked at that point and the land simply ran down to the muddy foreshore with landing stages and water gates. It required an Act of Parliament in 1771 to allow the Adam brothers to create an embankment with arched entrances into subterranean streets and storage areas and the Corporation of London was none too pleased at this infringement of its rights over the river. As well as the Mayor and Corporation they also managed to upset the Watermen and Lightermen’s Company, the Coal and Corn Lightermen and (somehow) the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey. A popular ditty of the time reveals the general prejudice against the oatmeal-eating Scots.

Four Scotsmen by the name of Adams

Who keep their coaches and their madams,

Quoth John in sulky mood to Thomas

Have stole the very river from us.

O Scotland, long has it been said

Their teeth are sharp for English bread

What seize our bread and water too….

Take all to gratify your pride

But dip your oatmeal in the Clyde.

The Adams brother might have got the site at a good price but they soon found themselves in financial difficulties as they constructed the magnificent terrace of eleven houses which made up Adelphi Terrace shown in the print at the top of the post. They had employed top-level craftsmen and artists on the interiors, including painter Angelica Kaufman. Then, no sooner had they begun than there was a spectacular banking crash “the Panic” of 1772 following the collapse of the Ayr Bank. The repercussions were far-reaching and had an effect in both Europe and America. Faced with bankruptcy they held a lottery in 1774 which cleared their debts (probably helped by the fact that, somehow, they managed to win the main prize themselves.) Their next scheme, Portland Place in Marylebone, built between 1776 and 1790, created further financial problems and with house prices in the Capital falling they found it hard to sell the Adelphi properties and cover their costs with prices falling from £1,000 to just over £300 between 1773 and 1779.

However, they persevered and, with the help of royal favour and celebrity endorsement (David Garrick the star of the stage was a friend and the artist Rowlandson lived there for many years) they went on to sell to a number of big names. Behind the Adelphi Terrace itself was a tight set of streets named after the brothers themselves, along with shops and apartments and the Royal Society of Arts (Below. John Adam Street).

Only a few of the original houses now remain and the fabulous Adelphi Terrace was demolished in 1938 and rebuilt. John Street and Duke Street are now John Adam Street and William Street is Durham House Street.

The vaults under the Terrace still partly exist and can be glimpsed from Lower Robert Street, off York Buildings.

The final print shows the Terrace in the early 19th century. On the left, the little building is the York Watergate, built in 1626 for the Duke of Buckingham to act as a smart entrance to a private landing and steps. It has now been placed in the Victoria Embankment Gardens, completely out of context.

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.

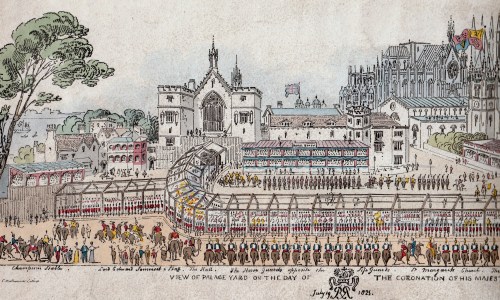

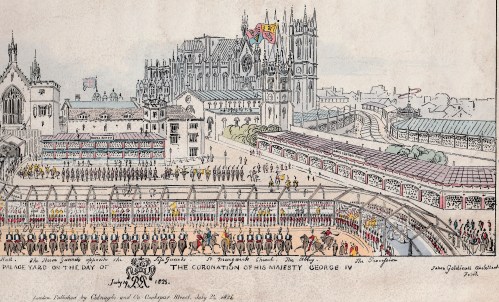

started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.