The Sunday Times newspaper on 7 January mentions the celebrations planned to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Astley’s Amphitheatre as the beginning of circus in England. This reminded me that I own a playbill for Astley’s for November 10th 1813 which features a tightrope act “being justly allowed the First Performer in the United Kingdom”. The Unparalleled Wilson’s act was complete with Wonderful Somersets (somersaults) and Surprising Leaps. Philip Astley, a six foot tall cavalryman, rose to the rank of sergeant major and left the army in 1768. With two horses he began to give unlicensed shows of horsemanship and riding lessons on open ground in Southwark. According to the London Encyclopedia he obtained a licence with the patronage of George III after subduing an out of control horse near Westminster Bridge. This enabled him to open ‘The Royal Grove’, a canvas-covered ring close to the southern end of Westminster Bridge in 1769. Today if you stand on the bridge and look towards St Thomas’s Hospital on the far bank you can see a patch of trees where the hospital gardens are. This is approximately the location of Astley’s, shown below in 1777.

Philip Astley, a six foot tall cavalryman, rose to the rank of sergeant major and left the army in 1768. With two horses he began to give unlicensed shows of horsemanship and riding lessons on open ground in Southwark. According to the London Encyclopedia he obtained a licence with the patronage of George III after subduing an out of control horse near Westminster Bridge. This enabled him to open ‘The Royal Grove’, a canvas-covered ring close to the southern end of Westminster Bridge in 1769. Today if you stand on the bridge and look towards St Thomas’s Hospital on the far bank you can see a patch of trees where the hospital gardens are. This is approximately the location of Astley’s, shown below in 1777.

Astley’s fame spread rapidly and in 1772 he performed before King Louis XV at Versailles. Patty, his wife, was also an accomplished rider. At first she assisted by beating out rhythms on a large drum but she soon joined in with horseback tricks including riding with a “muff” of swarms of bees over her hands and arms. Her husband began to incorporate comedy into his tricks, including his most famous act, The Tailor of Brentford.

Astley’s fame spread rapidly and in 1772 he performed before King Louis XV at Versailles. Patty, his wife, was also an accomplished rider. At first she assisted by beating out rhythms on a large drum but she soon joined in with horseback tricks including riding with a “muff” of swarms of bees over her hands and arms. Her husband began to incorporate comedy into his tricks, including his most famous act, The Tailor of Brentford.

As the popularity of his shows increased Astley gathered other acts, scouring fairs and going as far afield as Paris to find good street performers. The shows began to incorporate many of the circus acts we would recognise today – acrobats, jugglers, rope-dancers, clowns, strong men and, of course, the equestrian acts. The arena was roofed by 1780 so that he could continue to give shows year-round.

Astley is credited with discovering that the ideal size for a circus ring is 42 feet in diameter, allowing the optimal use of centrifugal force to keep him on the horse’s back as he galloped round the ring. However, Astley did not use the name ‘Circus’ for his show as this had been appropriated by Charles Dibden whom opened The Royal Circus nearby in 1782, stealing many of Astley’s ideas.

When The Royal Grove was destroyed by fire in 1794 he rebuilt in splendid style, this time calling it Astley’s Amphitheatre. By now it was so established, eclipsing Dibden’s Circus, that he could attract famous performers such as the clown Grimaldi and he added melodramas, comic sketches such as the one entitled ‘Honey Moon’ in the poster and dramatic sword fights. Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra on 23 August 1796 that she had arrived safely in London and that “We are to be at Astley’s tonight, which I am glad of.” Unfortunately there is no letter describing what she saw, but she sends lovers Harriet Smith and Robert Martin to Astley’s in Emma and Harriet “could dwell on it all with the utmost delight.”

As well as the ring the Amphitheatre had a stage with a proscenium arch linked to it by ramps allowing dramatic gallops from ring to stage. By the time the building was destroyed by fire again in 1803 Astley could afford to rebuild on a far more impressive scale as the print of 1803 [“*57-1633, Houghton Library, Harvard University”] shows.

Astley died in 1814 but the Amphitheatre continued to be wildly popular and would include crowd-pleasing shows recreating the battles of the Napoleonic Wars. Astley also contributed to the development of the circus by taking shows on tour in the summer months to wooden amphitheatres he’d had constructed throughout Britain and in eighteen cities on the Continent. He died in Paris and is buried there. The 1803 building lasted until a third fire in 1841. Charles Dickens describes it in Sketches By Boz as “delightful, splendid and surprising.” It was rebuilt in 1862 as the New Westminster Theatre Royal, but demolished in 1893.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

The view is from Leicester Place down to the North-East corner of the Square. If you stand there today you can still see the indentation in the street on the right hand side – I love how landholdings like this are reflected years later in the modern building line.

St Swithen’s was gutted during the Blitz, but remained standing as a ruin, complete with the Stone, until the 1960s when the church was demolished. The photograph below is 1962, just before the demolition. An unlovely building (111, Cannon Street) for the Bank of China was built on the site and the Stone was housed – or, rather, caged – behind bars in the front of this building.(Colour photo).

St Swithen’s was gutted during the Blitz, but remained standing as a ruin, complete with the Stone, until the 1960s when the church was demolished. The photograph below is 1962, just before the demolition. An unlovely building (111, Cannon Street) for the Bank of China was built on the site and the Stone was housed – or, rather, caged – behind bars in the front of this building.(Colour photo).

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

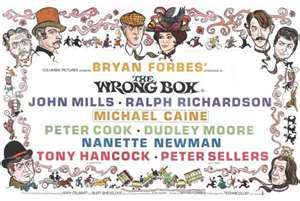

My first encounter with the concept of the tontine was in the film The Wrong Box (1966) which was based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1889 novel of the same name. The heirs of the two elderly Masterman brothers – the sole survivors of a tontine – engage in a range of hilarious and illegal tricks when it seems that one of the brothers has been killed in a train crash.

My first encounter with the concept of the tontine was in the film The Wrong Box (1966) which was based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1889 novel of the same name. The heirs of the two elderly Masterman brothers – the sole survivors of a tontine – engage in a range of hilarious and illegal tricks when it seems that one of the brothers has been killed in a train crash.

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.