In my blog posts about the weeks leading up to the battle of Waterloo I mentioned how long it took for the news of Napoleon’s escape from Elba to reach Paris. This was particularly surprising because the French had a magnificent telegraph system – defeated on this occasion, just when it was needed most, by poor visibility. The first visual telegraph system was the invention of Claude Chappe, a French engineer, working with his brothers. The French government seized on the invention and installed a network of 556 stations covering the entire country. S tations were updated and added to and the system continued in use until the 1850s when electric telegraphy took over. A Chappe telegraph and the posible positions are shown on the left.

tations were updated and added to and the system continued in use until the 1850s when electric telegraphy took over. A Chappe telegraph and the posible positions are shown on the left.

During the French wars the Allies were handicapped by poor communications while the French had this excellent system – provided visibility was good. The brothers invented a simple and robust system with two arms, each with a short upright at the end. This could be controlled by counterweights by one man. A message of 36 letters could reach Lille from Paris in about half an hour. Codes were also developed, so messages, including numbers, could be sent in plain, or code. in addition there was a 3-armed system used from 1803 onwards at coastal locations to warn of invasion. The Emperor was so convinced of the benefits of the telegraph that he took portable versions with him on campaign.

The British government was quick to see that without a telegraph system they were at a distinct disadvantage. The Admiralty’s Shutter Telegraph was created in 1795 to a design by Lord John Murray and had six rotating shutters which were used to indicate a complicated code. It required a rectangular framework tower with six, five feet high, octagonal shutters on horizontal axes that flipped between horizontal and vertical positions to signal. One was set up on top of the Admiralty building in Whitehall – more or less where the modern telecommunications masts can be seen today doing much the same job.

With a staggering disregard for security it was possible to visit the telegraph station, provided one tipped the operator. Presumably only reputable persons were permitted to enter the Admiralty in the first place, but it is still hard to believe that this was not a security loophole. The newspapers kept an eye on telegraph activity and could deduce when something major was about to happen by the volume of traffic and where it was going, even if they could not decipher it

activity and could deduce when something major was about to happen by the volume of traffic and where it was going, even if they could not decipher it

The first line ran from the Admiralty to the dockyards at Sheerness and on to Deal. It had 15 stations along the route and a message took an astonishing sixty seconds. The second went south from London to the naval base at Portsmouth and then on to Plymouth and was opened in May 1806. The third to Yarmouth on the east coast opened in 1808. The image on the left shows the telegraph array on top of the church on St Albans, Hertfordshire.

The intermediate stations were wooden huts and with a staggering lack of foresight they were all abandoned in 1814 when peace was declared and had to be recommissioned hastily in March 1815 when the news of Bonaparte’s escape from Elba reached London.

When peace came the enterprising Chappe brothers promoted their system for commercial use and some of their stone towers can still be found – there is one in Saverne, for example, and one at Baccon on the Loire, just west of Orleans which I visited a few years ago. (Photo, left, shows it with its restored telegraph arms).

Later in 1815 the Admiralty secured funding for a new system using arms rather than shutters and used the system – weather permit ting, until 1847. The brick tower on the right is the semaphore tower at Chatley Heath on the line to Portsmouth. It is now in the care of the National Trust.

ting, until 1847. The brick tower on the right is the semaphore tower at Chatley Heath on the line to Portsmouth. It is now in the care of the National Trust.

Receiving the News – the Telegraph System

Filed under Buildings, Napoleon, Science & technology

Going to the Library In Georgian London

In a recent post I used two of Cruickshank’s delightful monthly views of London to illustrate the state of the streets. When I looked at March I found it showed the effects of March gales on pedestrians passing the doors of Tilt, Bookseller & Publisher, which made me dig further into my collection to see what I had on access to books.

For the middle and upper classes in Georgian London reading was a significant leisure pastime, whether the book was a collection of sermons, a political dissertation, a scientific work or a scandalous novel full of haunted castles, wicked barons and innocent young ladies in peril.

To have a library, however modest, was the mark of a gentleman, but not everyone could afford every book that they wanted, or wanted to own every book that they read. The subscription circulating library came into existence to satisfy the reading habits of anyone who could afford a few pounds annual subscription and who required “Rational Entertainment In the Time of Rainy Weather, Long Evenings and Leisure Hours”, as the advertisement for James Creighton’s Circulating Library at no.14, Tavistock Street, Covent Garden put it in October 1808.

No doubt the elegant gentleman at the foot of this post would have satisfied his reading habit from one of these libraries. (He is sitting in his garden with a large bee skip in the background and is one of my favourite designs from my collection of bat-printed table wares. Bat printing refers to the method, by the way, and has nothing to do with flying mammals!)

The only bookshop and circulating library of the period that survives today is Hatchard’s in Piccadilly. It was established in 1797 and shared the street with Ridgeway’s and Stockdale’s libraries. The photograph of a modern book display in Hatchard’s was kindly sent to me by a reader who spotted my Walking Jane Austen’s London on the table. (2nd from the right, 2nd row from the front).

(2nd from the right, 2nd row from the front).

Circulating libraries ranged in size from the modest collection of books in a stationer’s shop to large and very splendid collections.

At the top end of the scale was the “Temple of the Muses”, the establishment of Messrs. Lackington and Allen in Finsbury Square. The print shows the main room with the counter under the imposing galleried dome and is dated April 1809. The accompanying text, in Ackermann’s Repository, states that it has a stock of a million volumes. The “Temple” was both a book shop and a circulating library and the p roprietors were also publishers and printers of their own editions. As well as the main room shown in the print there were also “two spacious and cheerful apartments looking towards Finsbury-square, which are elegantly fitted up with glass cases, inclosing books in superb bindings, as well as others of ancient printing, but of great variety and value. These lounging rooms, as they are termed, are intended merely for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen, to whom the bustle of the ware-room may be an interruption.”

roprietors were also publishers and printers of their own editions. As well as the main room shown in the print there were also “two spacious and cheerful apartments looking towards Finsbury-square, which are elegantly fitted up with glass cases, inclosing books in superb bindings, as well as others of ancient printing, but of great variety and value. These lounging rooms, as they are termed, are intended merely for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen, to whom the bustle of the ware-room may be an interruption.”

Circulating libraries advertised regularly in all the London newspapers and the advertisement here is a particularly detailed one from a new firm, Richard’s of 9, Cornhill and shows the subscription costs which varied between Town and Country. Special boxes were provided for the transport of books out of London, which was at the cost of the subscriber. Imagine the excitement of a lady living in some distant country house when the package arrived with one of the two books a month her subscription of 4 guineas had purchased!

Circulating libraries advertised regularly in all the London newspapers and the advertisement here is a particularly detailed one from a new firm, Richard’s of 9, Cornhill and shows the subscription costs which varied between Town and Country. Special boxes were provided for the transport of books out of London, which was at the cost of the subscriber. Imagine the excitement of a lady living in some distant country house when the package arrived with one of the two books a month her subscription of 4 guineas had purchased!

Filed under Books, Buildings, Entertainment, Gentlemen, Shopping, Street life, Women

The Perils of the Pavement – Winter in Georgian London

February always seems to bring muddier, messier weather than January, perhaps because the ground is already so sodden. Negotiating the slushy snow, puddles and potholes as I crossed the street in my local market town this morning made me think about what London streets were like at this time of year in the early 19th century.

The first print is from Richard Deighton’s London Nuisances series – A Heavy Fall of Snow – with the unfortunate gentleman getting a load of snow on his hat from the men clearing the ledge above the shop he is passing.

Rather appropriately the establishment belongs to Mr Careless, a skate maker, and pairs of skates are hanging in the window. The engraving shows very clearly the flagstones of the pavement, as opposed to the much rougher cobbled street surface which is just visible above the caption.

For all the accident with the snow, this seems a very clean and tidy street. For a rather more likely pair of images I’ve copied two of a monthly series of prints of London street scenes by George Cruikshank (thanks to Stephen Barker for the identification!). They were cut out and pasted in an album, hence the clipped corners. Except for the style of the women’s dresses and the gas lamp they could be any time from about 1800.

In the first, January, the town is experiencing a hard frost. The men in the carts are breaking up ice and taking it away, while three chilly individuals are marching under a placard reading “Poor Froze Out Gardeners” – presumably with no work because the ground is frozen solid. Behind their placard is the ship of W. Winter, Furrier and the shop window on the left is advertising “Soups”. A gang of boys seems to have fallen to the ground while sliding on the ice.

In the first, January, the town is experiencing a hard frost. The men in the carts are breaking up ice and taking it away, while three chilly individuals are marching under a placard reading “Poor Froze Out Gardeners” – presumably with no work because the ground is frozen solid. Behind their placard is the ship of W. Winter, Furrier and the shop window on the left is advertising “Soups”. A gang of boys seems to have fallen to the ground while sliding on the ice.

The second scene is February and shows the effects of the thaw. Men are shoveling snow off the high roofs in the background onto unwary passers-by and the cobbled street surface is a potholed mess. The lady in the middle with her skirts lifted almost to her knees is wearing iron pattens on her shoes to raise her out of the mire and street cleaners are shoveling mud into a cart behind her. The housewife on the corner is obviously doing her bit to sweep at least a section of the pavement clean. On the right the postman is doing his rounds. Here is one of a pair of late 18th century pattens like the ones being worn.

Filed under Accidents & emergencies, Street life, working life

Walking the Dog in Georgian London

It was this delightful French print of a dog groomer that started me wondering about Georgian Londoners and their pet dogs and looking through my print collection to see what I could find. The Tondeur des Chiens – or dog shearer – is from a set of about sixty prints by Adrien Joly (1772-1839) entitled Arts, Métiers et Cris de Paris par Joly d’après nature. They were published in c.1813. The groomer has his little box of tools with an attached advertising sign and wears clogs. Wisely he had tied up the muzzle of the shaggy hound who looks seriously displeased with the process.

It was this delightful French print of a dog groomer that started me wondering about Georgian Londoners and their pet dogs and looking through my print collection to see what I could find. The Tondeur des Chiens – or dog shearer – is from a set of about sixty prints by Adrien Joly (1772-1839) entitled Arts, Métiers et Cris de Paris par Joly d’après nature. They were published in c.1813. The groomer has his little box of tools with an attached advertising sign and wears clogs. Wisely he had tied up the muzzle of the shaggy hound who looks seriously displeased with the process.

I decided not to look for working dogs – hounds, ratting terriers and so forth, but for animals that seemed to be pets. This lady, wearing Winter Carriage Dress (La Belle Assemblee 1818) is accompanied on a rather muddy foreshore by what I think is a miniature spaniel (or is it?).

muddy foreshore by what I think is a miniature spaniel (or is it?).

The two ladies below on the right are from the Ladies’ Monthly Museum for 1801 and their dog appears to be a poodle wearing some sort of band on its front leg. Ornament or identification, I wonder?

appears to be a poodle wearing some sort of band on its front leg. Ornament or identification, I wonder?

Street scenes I can find with dogs in do not show them on leads and in some cases they are running about looking quite out of control.

The scene below is a detail of a print of Horse Guards Parade. The gentleman on the right has his dog – some sort of collie, possibly, under control, but in the centre a greyhound is chasing a smaller dog with a curly tail – right under the hooves of the advancing troopers. there also seem to be several dogs between the marching troops on the extreme left.

I have several of D T Egerton’s wonderful ‘Bores’ series of prints, published by Thomas McLean in 1824. in all of them the hero is subjected to some ‘boring’ occurrence – in this case, being shot in a duel! I am not certain whether the brown and white spaniel is with the nervous gentleman on the left or the cool one on the right.

I have several of D T Egerton’s wonderful ‘Bores’ series of prints, published by Thomas McLean in 1824. in all of them the hero is subjected to some ‘boring’ occurrence – in this case, being shot in a duel! I am not certain whether the brown and white spaniel is with the nervous gentleman on the left or the cool one on the right.

The detail below right is from the same series and shows the elegant officer being ‘bored’ by some unfashionable young man who is claiming acquaintance. The scene is outside the Clarendon Hotel in Bond Street and the officer is followed by his elegantly-clipped poodle.

And finally my favourite of the ‘Bores’ – how boring it is when the landlady discovers that you are not married to your pretty companion and throws you out on the pavement with all your possessions – including her parrot in a cage, pot plants and two little dogs. One looks like a miniature greyhound, the other is rather pug-like.

Filed under Animals, Gentlemen, Horse Guard's Parade, Love and Marriage

Books For Christmas

Is Christmas present money or a book token burning a hole in your pocket? Here are four of the non-fiction books I enjoyed most in 2014 and which I’d recommend to anyone interested in London’s history or the Georgian era. They aren’t all 2014 publications, but they were new to me last year.

Firstly, and probably my favouri te – the London Topographical Society’s reprint of John Tallis’s London Street Views 1838-1840. It has an index, introductory essay and a searchable index on CDRom. The views are a little later than my usual period of interest, but Tallis caught London just before the major Victorian rebuilding and redevelopments got under way and these strips maps showing the elevations of the buildings along each side, plus the names of the businesses in each are incredibly detailed. I own four of the original maps, but it was a lucky chance that I found them at a price I could afford – they are expensive collector’s pieces – so this volume is a real treat.

te – the London Topographical Society’s reprint of John Tallis’s London Street Views 1838-1840. It has an index, introductory essay and a searchable index on CDRom. The views are a little later than my usual period of interest, but Tallis caught London just before the major Victorian rebuilding and redevelopments got under way and these strips maps showing the elevations of the buildings along each side, plus the names of the businesses in each are incredibly detailed. I own four of the original maps, but it was a lucky chance that I found them at a price I could afford – they are expensive collector’s pieces – so this volume is a real treat. The example above is a detail from one of my originals and shows part of St James’s Street.

The example above is a detail from one of my originals and shows part of St James’s Street.

My next choice is Ben Wilson’s Decency & Disorder: 1789-1837, a scholarly, but very readable account of how the boisterous Georgians, valuing liberty and personal freedom above civil order and ‘decency’ and shunning the idea of a police force as foreign and oppressive, changed to adopt ‘Victorian values’ and an organized police force.

My next choice is Ben Wilson’s Decency & Disorder: 1789-1837, a scholarly, but very readable account of how the boisterous Georgians, valuing liberty and personal freedom above civil order and ‘decency’ and shunning the idea of a police force as foreign and oppressive, changed to adopt ‘Victorian values’ and an organized police force.

I particularly enjoyed the story of the Georgian gentleman who, such was his sensibility, was so overcome by the beauty of the scene that he was lost for words and could only cast himself, face-down, into a flowerbed in Bath. And then there was the member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice who forced himself to buy hand-carved sex toys at a prisoner of war market and then found himself at a loss to send them to the London headquarters. They were, he complained, too bulky to be enclosed in a letter.

Thirdly there is John Styles The Dress of the Common People: everyday fashion in eighteenth century England. Despite the title this lavishly illustrated and very scholarly work covers the Georgian era rather than the 18th century exactly. I found it in, of all places, the National Park bookstore in Salem, Massachusetts, but it is available in the UK.

It is a refreshing change from books of high-end fashion plates and includes information about fabrics and the cost of clothing, where people bought their clothing and a host of other details.

My final choice was too large to go on my scanner, so here is part of the cover of Royal River: power, pageantry and the Thames published for a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. (Guest curator, David Starkey).

The illustrations are gorgeous and the book ranges from topics as diverse as the lord Mayor’s Procession, Lord Nelson’s funeral procession, royal yachts and the transformation of the Thames in the Victorian era.

The illustrations are gorgeous and the book ranges from topics as diverse as the lord Mayor’s Procession, Lord Nelson’s funeral procession, royal yachts and the transformation of the Thames in the Victorian era.

Best wishes for Christmas and the new year to all my readers!

Louise

Filed under Books, Buildings, Christmas, Fashions, Transport and travel

Cordwainer, Shoemaker, Cobbler? Where would Georgian Londoners Buy Their Shoes?

I have shoemakers in my ancestry through the 15th to 19th century. Sometimes they are described as cordwainers, sometimes shoemakers. So what is the difference, and where would you have gone to buy your shoes if you were a Georgian Londoner – from a cordwainer, a shoemaker or a cobbler?

(Greetings, by the way, if you have Hurst ancestors in Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire or Oxfordshire we are probably cousins!)

The term cordwainer, according to the Honourable Cordwainer’s Company’s website, “is an Anglicization of the French word cordonnier, which means shoemaker, introduced into the English language after the Norman invasion in 1066. The word was derived from the city of Cordoba in the south of Spain… Moorish Cordoba was celebrated in the early Middle Ages for silversmithing and the production of cordouan leather, called “cordwain” in England… Crusaders brought home much plunder and loot, including the finest leather the English shoemakers had seen. Gradually cordouan, or cordovan leather became the material most in demand for the finest footwear in all of Europe.”

Shoemakers who chose to call themselves cordwainers were implying that they used only the finest materials, and therefore produced only the finest footwear. Cobblers, on the other hand, were not working with new leather. They were repairing shoes, or “cobbling together” new shoes from old.

This trade card was produced by “The Friendly Institution of Cordwainers of Leeds” in 1802. The reference to “the Sons of Crispin” is to St Crispin, the patron saint of shoemakers.

This trade card was produced by “The Friendly Institution of Cordwainers of Leeds” in 1802. The reference to “the Sons of Crispin” is to St Crispin, the patron saint of shoemakers.

If you were a Georgian in London looking for footwear you had a choice ranging from the finest made-to measure products of a high-end cordwainer to the reworked product of the cobbler on the corner – or even simply second-hand from a market stall.

These exquisite blue satin shoes are in the Museum of London and date from the 1760s. The label inside reads ‘Fras Poole, Woman’s Shoemaker in the Old Change, near Cheapside London’. They show the high level of craftsmanship required for top-end footwear – and the range of craftspeople who would have been employed. Much simpler, and closer to Jane Austen’s day, are these delicate pink silk-satin ankle boots with their thin soles and fragile silk laces in my collection (below). They had absolutely no internal support for the sole of the foot.

These exquisite blue satin shoes are in the Museum of London and date from the 1760s. The label inside reads ‘Fras Poole, Woman’s Shoemaker in the Old Change, near Cheapside London’. They show the high level of craftsmanship required for top-end footwear – and the range of craftspeople who would have been employed. Much simpler, and closer to Jane Austen’s day, are these delicate pink silk-satin ankle boots with their thin soles and fragile silk laces in my collection (below). They had absolutely no internal support for the sole of the foot.

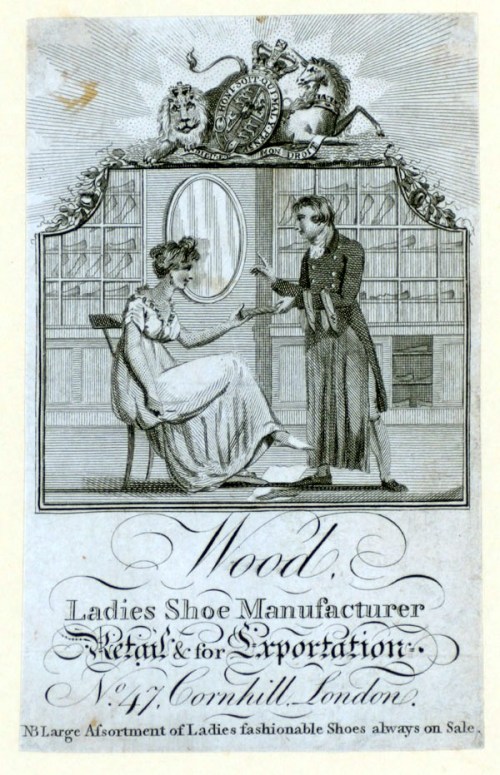

For the well-to-do, shoes were purchased from a shop which might display the products of one maker, or several. The trade card at the top of this post shows a fashionable lady being served. In the background are display cabinets containing a range of styles. As the card says, “Large Assortment of Ladies fashionable Shoes always on Sale.” For such a tiny scrap of cardboard the detail is considerable. The lady is seated with a mat in front of her to protect her unshod feet (or the new shoes?). She is being served by a man – the norm in high-class retail establishments – and he is carrying shoes over his arm in a way that shows that pairs were tied together. The assistant is smartly dressed, but wearing a long apron, which makes me wonder whether he would kneel down for the lady to place her foot on his knee.

For the well-to-do, shoes were purchased from a shop which might display the products of one maker, or several. The trade card at the top of this post shows a fashionable lady being served. In the background are display cabinets containing a range of styles. As the card says, “Large Assortment of Ladies fashionable Shoes always on Sale.” For such a tiny scrap of cardboard the detail is considerable. The lady is seated with a mat in front of her to protect her unshod feet (or the new shoes?). She is being served by a man – the norm in high-class retail establishments – and he is carrying shoes over his arm in a way that shows that pairs were tied together. The assistant is smartly dressed, but wearing a long apron, which makes me wonder whether he would kneel down for the lady to place her foot on his knee.

This is certainly the case lower down the social scale. The print below shows a shoe shop which appears to be selling only products made on the premises – both men’s and women’s boots and shoes. One lady has her foot on the knee of the salesman while her friend, wearing a riding habit, tries on a boot. In this much less refined setting a passerby ogles the ladies.

At the end of the 18th century small change was scarce and many businesses produced copper tokens which took the place of low denomination coins. I have two from shoemakers. One is for Carter of Jermyn Street. Dated 1792 it shows an elegant lady’s shoe with heel. The other is for Guests Patent Boots & Shoes of No.9, Surry Street, Blackfriars Road (1795) and shows a lady’s slipper, a man’s shoe and a boot.

Fashionable gentlemen took great pride in their boots and perhaps the most famous of all the London bootmakers was George Hoby whose shop was at the top of St James’s Street. Hoby was arrogant, and far from subservient to his aristocratic patrons, but he died a very rich man, famous for producing the iconic Wellington Boot to the duke’s special requirements.

This billhead is from an account sent by Hoby to Major Crowder (who, incidentally, was the officer who intercepted the coach carrying Napoleon’s secret codes in the Peninsula). The billhead shows the royal coat of arms and names Hoby’s royal patrons. It also includes a do it yourself guide for measuring for boots – presumably this was for the convenience of officers serving abroad, or country gentlemen.

To see a range of men’s footwear across the classes, this print by Thomas Edgerton from the ‘Bores’ series of 1828 is ideal. The gentleman has been interrupted as he pulls on his boots after breakfast. A beadle accompanies an aggrieved father who is complaining about the seduction of his daughter by the valet. These boots are elegant items in very soft leather with the spurs already attached, and they are pulled on using special boot-pullers and loops in the top of the boot. The gentleman’s backless bedroom slippers are by his chair. His valet wears black pumps with natty striped stockings, contrasting to the solid and old-fashioned respectability of the beadle’s buckled shoes. Finally the father wears practical riding boots with tan tops.

At the lower end of the market, shoemakers would produce a range of sizes and the customer would come in and buy ‘off the peg.’ For made to measure shoes a wooden last would be made to the customer’s exact measurements, kept in store and modified by cutting away wood, or adding leather patches, as the foot shape changed over time. To see a last-maker in action you can go into Lobb’s in St James’s Street. Although established a little later than the Regency they still produce hand-made shoes in the traditional manner and their display cases have some fascinating old examples.

I was in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, recently and visited the shoemaker’s shop there. The photo is of him working to produce the everyday leather shoes that the re-enactors use on the site. These are sturdy, off the peg styles, and are very similar to the shoes and boots illustrated by W H Pyne in his “Rustic Figures”, a series of sketches to guide amateur artists.

I was in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, recently and visited the shoemaker’s shop there. The photo is of him working to produce the everyday leather shoes that the re-enactors use on the site. These are sturdy, off the peg styles, and are very similar to the shoes and boots illustrated by W H Pyne in his “Rustic Figures”, a series of sketches to guide amateur artists.

Horse Guards Parade – Crocodiles, Cardinal Wolsey & Beach Volleyball

One of the emptiest, yet most evocative, spaces in London is Horse Guards Parade. In my last post I wrote about the Regent’s Bomb – the fantastical mortar and gun carriage that sits on one side of the Arch. This time I’m writing about a little of the history of the parade ground and another cannon with a wonderful gun carriage.

Horse Guards Parade sits between Whitehall and St James’s Park and began life as open land next to the grounds of York Place, the London palace of the Archbishops of York. Its main entrance faced down the road that is now Horse Guards Avenue, the bishop’s route to his landing stage on the river. With the fall of Cardinal Wolsey Henry VIII seized York Place and then set about acquiring “…all the medowes about saynt James, and all the whole house of S.James and ther made a fayre manision and a parke…” according to Edward Hall.

When the king began his work on what was to become Whitehall Palace a willow marsh for the farming of osiers for basketwork, Steynour’s Croft, covered much of what is now Horse Guards, the Bell Inn stood at the southern edge and an old track crossed it from the scrubland that became St James’s Park.

By 1534 the Palace of Whitehall was largely complete. Part of the area, a longitudinal strip running west across Horse Guards became his tiltyard, scene of tournaments and knightly exercises. Under Elizabeth I the Tiltyard was used for animal baiting and tournaments and pageants which were set pieces for state occasions. Under James I elaborate masques were held – including one involving an elephant carrying a castle – but the increasingly theatrical nature of royal masques led to the building of the Banqueting House on the other side of what was then King Street (now Whitehall) and the last masque in the tiltyard was planned for 1624. After that it became known as the Bearstake Gallery and it continued to be used for baiting sports until 1660.

A standing guard was stationed in a specially built guardroom at the tiltyard from 1641 and the area continued to house soldiers throughout the Commonwealth period.

On May 8th 1660 Charles II was proclaimed on the site of the old Tiltyard ‘Green’ and the renovation of Whitehall Palace began. A plan of c1670 shows Whitehall as a wide street coming down from the north and ending at the pinch-point of a Tudor gate. The range of buildings that were the old Horse Guards were built in 1663 with a yard in front and behind the range the open expanse of ground that became Horse Guards Parade.

In January 1698 a great fire destroyed the Palace of Whitehall, sparing only the Banqueting Hall and Old Horse Guards. A letter of the time records, “All parts from near the house my Lord Lichfield lived in to the Horse Guards were yesterday covered with heaps of goods rescued from the flames.”

The king moved to St James’s Palace, across the park, and Whitehall became the location for many government offices and from the 1730s the buildings surrounding Horse Guards were gradually replaced. The dilapidated old building was demolished in 1750 and the new building – the one we see now – was designed by William Kent, with additions by Isaac Ware.

The large open space was referred to as the Parade ground, but the first written reference to “Horse Guards Parade” as a title comes as late as 1817. By then the area looked much as it does today as can be seen in this print of 1809 by Rowlandson and Pugin, published by Ackermann. Only the high brick wall that closes off the gardens at the rear of Downing Street today (to the right of the picture) is missing.

The space is uncluttered now – when it is not being used for events such as Trooping the Colour and the Olympic Beach Volleyball, or in the Victorian era, the marshalling point for the vast funeral procession of the Duke of Wellington. However there are two interesting weapons exhibited there, either side of the arch. On one side is the Regent’s Bomb, on the other a 16th century Turkish cannon brought to the site in 1802 after its

capture in the siege of Alexandria (1801) when the British invaded Egypt to fight Napoleon’s army, an event that formed the setting for my recent novel Beguiled By

Her Betrayer.

It was made in 1526 and the inscription on the barrel reads:

“The Solomon of the age the Great Sultan Commander of the dragon guns When they breathe roaring like thunder. May the enemy’s forts be razed to the ground. Year of Hegira 931.”

The gun carriage was made at Woolwich and depicts Britannia pointing at the Pyramids and a rather splendid crocodile. You can visit Horse Guards Parade both in my Walks Through Regency London (Walk 8 Trafalgar Square to Westminster, which follows the length of Whitehall)

and Walking Jane Austen’s London (Walk 6 Westminster to Charing Cross, which goes through St James’s Park).

Filed under Buildings, London Parks, Monuments, St James's Park

The Regent’s Bomb

Horse Guards’ Parade lies between St James’ Park and Whitehall and has many historical connections – it was Henry VIII’s tiltyard for the Palace of Whitehall, it was the only open place in London big enough for the funeral procession of the Duke of Wellington to form up in, it is the location for today’s Trooping the Colour ceremony – and it was even the location for the beach volleyball in the 2012 Olympics.

It is also the home of possibly the most eccentric piece of ordnance in the British Isles – the Prince Regent’s Bomb. It is a mortar, a squat black cannon captured from the French during the battle of Salamanca in 1812. The battle resulted in the lifting of the siege of Cadiz and the mortar was presented to the Prince Regent “as a token of respect and gratitude by the Spanish nation.”

The plain and simple mortar was sent to Woolwich Arsenal and there a support and plinth was made for it in the shape of a dragon. It is a truly stupendous and bizarre construction and was unveiled, with great ceremony, on the 12th August 1816, the Prince’s birthday. Immediately it attracted ridicule, for not only was the design completely over the top, as only something designed to appeal to the Prince of Wales’s taste could be, but “Bomb” sounded irresistibly like “Bum” and the Regent’s substantial backside was already the subject of many coarse caricatures.

Perhaps the cruelest is a companion to the verses below. I have not been able to locate a copyright-free image, but you can find it here in the British Museum’s collection http://tinyurl.com/p6fxayy

The verses come from a broadsheet published by William Hone in 1816. I have filled in names that have been left blank in square brackets [ ]. The three ‘secret hags’ are the Regent’s three mistresses. ‘Old Bags’ was the Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon (More about him in my post of April 21 2014: The Eloping Lord Chancellor). Vansittart was Nicholas Vansittart, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Tory Wellesley was Wellesley-Pole, elder brother of the Duke of Wellington, Castlereagh was Foreign Secretary and leader of the House of Commons and George Rose was Treasurer of the Navy. (My thanks to fellow historical novelist Melinda Hammond for help filling in the blanks (http://www.melinda-hammond.co.uk)

ON THE REGENT’S BOMB

Being uncovered, in St. James’s Park, on Monday, the 12th of August, 1816, His Royal Highness’s Birth-Day.

Oh! all ye Muses, hither come—

And celebrate the Regent’s bomb!

Illustrious Bomb! Immortal capture!

Thou fill’st my every sense with rapture!

Oh, such a Bomb! so full of fire—

Apollo—hither bring thy lyre—

And all ye powers of music come,

And aid me sing this mighty Bomb!

And first, with reverence this I note—

This Bomb was once a Sans culotte—

And next, by changes immaterial,

Became, at length, a Bomb Imperial!

And first exploded—pardon ladies!—

With loud report, at siege of Cadiz—

At which this Bomb—so huge and hearty,

Belonged to little Buonaparté;

But now, by strange metamorphosis,

(A kind of Bomb metempsychosis)

Has—though it odd may seem—become

Our gracious R[egen]t’s royal Bomb;

Who, after due consideration,

Resolved, to gratify the Nation—

Nor let his natal day pass over

Without some feat—to then uncover,

And there display—to strike us dumb—

His vast—unfathomable Bomb!

Oh, what a Bomb! Oh, Heaven defend us!

The thought of Bombs is quite tremendous!

What crowds will come from every shore

To gaze on its amazing bore!

What swarms of Statesmen, warm and loyal,

To worship Bomb so truly royal!

And first approach three ‘secret hags,’

Then him the R[egen]t calls ‘Old Bags;’

Methinks I see V[ansittar]t come,

And humbly kiss the royal Bomb!

While T[or]y W[ellesle]y, (loyal soul)

Will take its measure with a Pole;

And C[astlereag]h will low beseech

To kiss a corner of the breech;

And next will come of G[eorg]y R[os]e,

And in the touch-hole shove his nose!

For roundness, smoothness, breech, and bore,

Such Bomb was never seen before!

Then, Britain! be not this forgotten,

That, when we all are dead and rotten,

And every other trace is gone

Of all thy matchless glory won,

This mighty Bomb shall grace thy fame

And boast thy glorious Regent’s name!

In every age such pilgrims may go

As far t’outrival fam’d St. Jago!

And, centuries hence, the folks shall come,

And contemplate–the Regent’s Bomb!

[by] BOMBASTES.

August 12, 1816.

“Bombastes” might have been surprised to discover that two hundred years later folks still come “and contemplate the Regent’s Bomb!” You’ll find the Prince’s Bomb on Walk 6 in my Walking Jane Austen’s London.

Filed under London Parks, Monuments, Prince Regent, Regency caricatures, Royalty, Walks

Writing Historical Fiction – The Westminster Way: a free all day event

On Saturday 11th October I’ll be at the City of Westminster Archives Centre, 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE for a *free* all day event –

Writing Historical Fiction…

…the Westminster Way!

10:00am- 4:00pm

10:00am- 10:45pm Tour: Westminster Archives search room

11:15am- 1:00pm Walk: A walk around Georgian Westminster

2:00pm- 4:00pm Talk: Resources for Writing Historical Fiction

To get your free ticket simply call the Archives Centre on 020 7641 5180

Archive staff will talk you through how to explore the wealth of riches in their collection and will have fascinating items on display for you to take a close-up look. On my walk we will pass from some of the worst slums in London to the centre of power and privilege, join Wordsworth on Westminster Bridge, see where the semaphore towers sending signals to Nelson’s fleet have been replaced by modern wireless aerials, view the Prince of Wales’ Bomb and locate the site of Astley’s Ampitheatre before returning past where Charles II’s ostriches lived, down Cockpit Steps in the wake of Hogarth and back to the Archives Centre.

the wake of Hogarth and back to the Archives Centre.

In the afternoon I’ll be giving an illustrated talk about how the Archives can help you dig deep into the past for your historical writing.

Illustrations:

Top of the page: one of the vivid prints from the Archive Centre collection

Above: The Royal Cockpit by Hogarth

Filed under Books, London Parks, Walks