In my blog posts about the weeks leading up to the battle of Waterloo I mentioned how long it took for the news of Napoleon’s escape from Elba to reach Paris. This was particularly surprising because the French had a magnificent telegraph system – defeated on this occasion, just when it was needed most, by poor visibility. The first visual telegraph system was the invention of Claude Chappe, a French engineer, working with his brothers. The French government seized on the invention and installed a network of 556 stations covering the entire country. S tations were updated and added to and the system continued in use until the 1850s when electric telegraphy took over. A Chappe telegraph and the posible positions are shown on the left.

tations were updated and added to and the system continued in use until the 1850s when electric telegraphy took over. A Chappe telegraph and the posible positions are shown on the left.

During the French wars the Allies were handicapped by poor communications while the French had this excellent system – provided visibility was good. The brothers invented a simple and robust system with two arms, each with a short upright at the end. This could be controlled by counterweights by one man. A message of 36 letters could reach Lille from Paris in about half an hour. Codes were also developed, so messages, including numbers, could be sent in plain, or code. in addition there was a 3-armed system used from 1803 onwards at coastal locations to warn of invasion. The Emperor was so convinced of the benefits of the telegraph that he took portable versions with him on campaign.

The British government was quick to see that without a telegraph system they were at a distinct disadvantage. The Admiralty’s Shutter Telegraph was created in 1795 to a design by Lord John Murray and had six rotating shutters which were used to indicate a complicated code. It required a rectangular framework tower with six, five feet high, octagonal shutters on horizontal axes that flipped between horizontal and vertical positions to signal. One was set up on top of the Admiralty building in Whitehall – more or less where the modern telecommunications masts can be seen today doing much the same job.

With a staggering disregard for security it was possible to visit the telegraph station, provided one tipped the operator. Presumably only reputable persons were permitted to enter the Admiralty in the first place, but it is still hard to believe that this was not a security loophole. The newspapers kept an eye on telegraph activity and could deduce when something major was about to happen by the volume of traffic and where it was going, even if they could not decipher it

activity and could deduce when something major was about to happen by the volume of traffic and where it was going, even if they could not decipher it

The first line ran from the Admiralty to the dockyards at Sheerness and on to Deal. It had 15 stations along the route and a message took an astonishing sixty seconds. The second went south from London to the naval base at Portsmouth and then on to Plymouth and was opened in May 1806. The third to Yarmouth on the east coast opened in 1808. The image on the left shows the telegraph array on top of the church on St Albans, Hertfordshire.

The intermediate stations were wooden huts and with a staggering lack of foresight they were all abandoned in 1814 when peace was declared and had to be recommissioned hastily in March 1815 when the news of Bonaparte’s escape from Elba reached London.

When peace came the enterprising Chappe brothers promoted their system for commercial use and some of their stone towers can still be found – there is one in Saverne, for example, and one at Baccon on the Loire, just west of Orleans which I visited a few years ago. (Photo, left, shows it with its restored telegraph arms).

Later in 1815 the Admiralty secured funding for a new system using arms rather than shutters and used the system – weather permit ting, until 1847. The brick tower on the right is the semaphore tower at Chatley Heath on the line to Portsmouth. It is now in the care of the National Trust.

ting, until 1847. The brick tower on the right is the semaphore tower at Chatley Heath on the line to Portsmouth. It is now in the care of the National Trust.

Category Archives: Buildings

Receiving the News – the Telegraph System

Filed under Buildings, Napoleon, Science & technology

Going to the Library In Georgian London

In a recent post I used two of Cruickshank’s delightful monthly views of London to illustrate the state of the streets. When I looked at March I found it showed the effects of March gales on pedestrians passing the doors of Tilt, Bookseller & Publisher, which made me dig further into my collection to see what I had on access to books.

For the middle and upper classes in Georgian London reading was a significant leisure pastime, whether the book was a collection of sermons, a political dissertation, a scientific work or a scandalous novel full of haunted castles, wicked barons and innocent young ladies in peril.

To have a library, however modest, was the mark of a gentleman, but not everyone could afford every book that they wanted, or wanted to own every book that they read. The subscription circulating library came into existence to satisfy the reading habits of anyone who could afford a few pounds annual subscription and who required “Rational Entertainment In the Time of Rainy Weather, Long Evenings and Leisure Hours”, as the advertisement for James Creighton’s Circulating Library at no.14, Tavistock Street, Covent Garden put it in October 1808.

No doubt the elegant gentleman at the foot of this post would have satisfied his reading habit from one of these libraries. (He is sitting in his garden with a large bee skip in the background and is one of my favourite designs from my collection of bat-printed table wares. Bat printing refers to the method, by the way, and has nothing to do with flying mammals!)

The only bookshop and circulating library of the period that survives today is Hatchard’s in Piccadilly. It was established in 1797 and shared the street with Ridgeway’s and Stockdale’s libraries. The photograph of a modern book display in Hatchard’s was kindly sent to me by a reader who spotted my Walking Jane Austen’s London on the table. (2nd from the right, 2nd row from the front).

(2nd from the right, 2nd row from the front).

Circulating libraries ranged in size from the modest collection of books in a stationer’s shop to large and very splendid collections.

At the top end of the scale was the “Temple of the Muses”, the establishment of Messrs. Lackington and Allen in Finsbury Square. The print shows the main room with the counter under the imposing galleried dome and is dated April 1809. The accompanying text, in Ackermann’s Repository, states that it has a stock of a million volumes. The “Temple” was both a book shop and a circulating library and the p roprietors were also publishers and printers of their own editions. As well as the main room shown in the print there were also “two spacious and cheerful apartments looking towards Finsbury-square, which are elegantly fitted up with glass cases, inclosing books in superb bindings, as well as others of ancient printing, but of great variety and value. These lounging rooms, as they are termed, are intended merely for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen, to whom the bustle of the ware-room may be an interruption.”

roprietors were also publishers and printers of their own editions. As well as the main room shown in the print there were also “two spacious and cheerful apartments looking towards Finsbury-square, which are elegantly fitted up with glass cases, inclosing books in superb bindings, as well as others of ancient printing, but of great variety and value. These lounging rooms, as they are termed, are intended merely for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen, to whom the bustle of the ware-room may be an interruption.”

Circulating libraries advertised regularly in all the London newspapers and the advertisement here is a particularly detailed one from a new firm, Richard’s of 9, Cornhill and shows the subscription costs which varied between Town and Country. Special boxes were provided for the transport of books out of London, which was at the cost of the subscriber. Imagine the excitement of a lady living in some distant country house when the package arrived with one of the two books a month her subscription of 4 guineas had purchased!

Circulating libraries advertised regularly in all the London newspapers and the advertisement here is a particularly detailed one from a new firm, Richard’s of 9, Cornhill and shows the subscription costs which varied between Town and Country. Special boxes were provided for the transport of books out of London, which was at the cost of the subscriber. Imagine the excitement of a lady living in some distant country house when the package arrived with one of the two books a month her subscription of 4 guineas had purchased!

Filed under Books, Buildings, Entertainment, Gentlemen, Shopping, Street life, Women

Books For Christmas

Is Christmas present money or a book token burning a hole in your pocket? Here are four of the non-fiction books I enjoyed most in 2014 and which I’d recommend to anyone interested in London’s history or the Georgian era. They aren’t all 2014 publications, but they were new to me last year.

Firstly, and probably my favouri te – the London Topographical Society’s reprint of John Tallis’s London Street Views 1838-1840. It has an index, introductory essay and a searchable index on CDRom. The views are a little later than my usual period of interest, but Tallis caught London just before the major Victorian rebuilding and redevelopments got under way and these strips maps showing the elevations of the buildings along each side, plus the names of the businesses in each are incredibly detailed. I own four of the original maps, but it was a lucky chance that I found them at a price I could afford – they are expensive collector’s pieces – so this volume is a real treat.

te – the London Topographical Society’s reprint of John Tallis’s London Street Views 1838-1840. It has an index, introductory essay and a searchable index on CDRom. The views are a little later than my usual period of interest, but Tallis caught London just before the major Victorian rebuilding and redevelopments got under way and these strips maps showing the elevations of the buildings along each side, plus the names of the businesses in each are incredibly detailed. I own four of the original maps, but it was a lucky chance that I found them at a price I could afford – they are expensive collector’s pieces – so this volume is a real treat. The example above is a detail from one of my originals and shows part of St James’s Street.

The example above is a detail from one of my originals and shows part of St James’s Street.

My next choice is Ben Wilson’s Decency & Disorder: 1789-1837, a scholarly, but very readable account of how the boisterous Georgians, valuing liberty and personal freedom above civil order and ‘decency’ and shunning the idea of a police force as foreign and oppressive, changed to adopt ‘Victorian values’ and an organized police force.

My next choice is Ben Wilson’s Decency & Disorder: 1789-1837, a scholarly, but very readable account of how the boisterous Georgians, valuing liberty and personal freedom above civil order and ‘decency’ and shunning the idea of a police force as foreign and oppressive, changed to adopt ‘Victorian values’ and an organized police force.

I particularly enjoyed the story of the Georgian gentleman who, such was his sensibility, was so overcome by the beauty of the scene that he was lost for words and could only cast himself, face-down, into a flowerbed in Bath. And then there was the member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice who forced himself to buy hand-carved sex toys at a prisoner of war market and then found himself at a loss to send them to the London headquarters. They were, he complained, too bulky to be enclosed in a letter.

Thirdly there is John Styles The Dress of the Common People: everyday fashion in eighteenth century England. Despite the title this lavishly illustrated and very scholarly work covers the Georgian era rather than the 18th century exactly. I found it in, of all places, the National Park bookstore in Salem, Massachusetts, but it is available in the UK.

It is a refreshing change from books of high-end fashion plates and includes information about fabrics and the cost of clothing, where people bought their clothing and a host of other details.

My final choice was too large to go on my scanner, so here is part of the cover of Royal River: power, pageantry and the Thames published for a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. (Guest curator, David Starkey).

The illustrations are gorgeous and the book ranges from topics as diverse as the lord Mayor’s Procession, Lord Nelson’s funeral procession, royal yachts and the transformation of the Thames in the Victorian era.

The illustrations are gorgeous and the book ranges from topics as diverse as the lord Mayor’s Procession, Lord Nelson’s funeral procession, royal yachts and the transformation of the Thames in the Victorian era.

Best wishes for Christmas and the new year to all my readers!

Louise

Filed under Books, Buildings, Christmas, Fashions, Transport and travel

Horse Guards Parade – Crocodiles, Cardinal Wolsey & Beach Volleyball

One of the emptiest, yet most evocative, spaces in London is Horse Guards Parade. In my last post I wrote about the Regent’s Bomb – the fantastical mortar and gun carriage that sits on one side of the Arch. This time I’m writing about a little of the history of the parade ground and another cannon with a wonderful gun carriage.

Horse Guards Parade sits between Whitehall and St James’s Park and began life as open land next to the grounds of York Place, the London palace of the Archbishops of York. Its main entrance faced down the road that is now Horse Guards Avenue, the bishop’s route to his landing stage on the river. With the fall of Cardinal Wolsey Henry VIII seized York Place and then set about acquiring “…all the medowes about saynt James, and all the whole house of S.James and ther made a fayre manision and a parke…” according to Edward Hall.

When the king began his work on what was to become Whitehall Palace a willow marsh for the farming of osiers for basketwork, Steynour’s Croft, covered much of what is now Horse Guards, the Bell Inn stood at the southern edge and an old track crossed it from the scrubland that became St James’s Park.

By 1534 the Palace of Whitehall was largely complete. Part of the area, a longitudinal strip running west across Horse Guards became his tiltyard, scene of tournaments and knightly exercises. Under Elizabeth I the Tiltyard was used for animal baiting and tournaments and pageants which were set pieces for state occasions. Under James I elaborate masques were held – including one involving an elephant carrying a castle – but the increasingly theatrical nature of royal masques led to the building of the Banqueting House on the other side of what was then King Street (now Whitehall) and the last masque in the tiltyard was planned for 1624. After that it became known as the Bearstake Gallery and it continued to be used for baiting sports until 1660.

A standing guard was stationed in a specially built guardroom at the tiltyard from 1641 and the area continued to house soldiers throughout the Commonwealth period.

On May 8th 1660 Charles II was proclaimed on the site of the old Tiltyard ‘Green’ and the renovation of Whitehall Palace began. A plan of c1670 shows Whitehall as a wide street coming down from the north and ending at the pinch-point of a Tudor gate. The range of buildings that were the old Horse Guards were built in 1663 with a yard in front and behind the range the open expanse of ground that became Horse Guards Parade.

In January 1698 a great fire destroyed the Palace of Whitehall, sparing only the Banqueting Hall and Old Horse Guards. A letter of the time records, “All parts from near the house my Lord Lichfield lived in to the Horse Guards were yesterday covered with heaps of goods rescued from the flames.”

The king moved to St James’s Palace, across the park, and Whitehall became the location for many government offices and from the 1730s the buildings surrounding Horse Guards were gradually replaced. The dilapidated old building was demolished in 1750 and the new building – the one we see now – was designed by William Kent, with additions by Isaac Ware.

The large open space was referred to as the Parade ground, but the first written reference to “Horse Guards Parade” as a title comes as late as 1817. By then the area looked much as it does today as can be seen in this print of 1809 by Rowlandson and Pugin, published by Ackermann. Only the high brick wall that closes off the gardens at the rear of Downing Street today (to the right of the picture) is missing.

The space is uncluttered now – when it is not being used for events such as Trooping the Colour and the Olympic Beach Volleyball, or in the Victorian era, the marshalling point for the vast funeral procession of the Duke of Wellington. However there are two interesting weapons exhibited there, either side of the arch. On one side is the Regent’s Bomb, on the other a 16th century Turkish cannon brought to the site in 1802 after its

capture in the siege of Alexandria (1801) when the British invaded Egypt to fight Napoleon’s army, an event that formed the setting for my recent novel Beguiled By

Her Betrayer.

It was made in 1526 and the inscription on the barrel reads:

“The Solomon of the age the Great Sultan Commander of the dragon guns When they breathe roaring like thunder. May the enemy’s forts be razed to the ground. Year of Hegira 931.”

The gun carriage was made at Woolwich and depicts Britannia pointing at the Pyramids and a rather splendid crocodile. You can visit Horse Guards Parade both in my Walks Through Regency London (Walk 8 Trafalgar Square to Westminster, which follows the length of Whitehall)

and Walking Jane Austen’s London (Walk 6 Westminster to Charing Cross, which goes through St James’s Park).

Filed under Buildings, London Parks, Monuments, St James's Park

Turn Again Whittington – there’s a traffic jam ahead

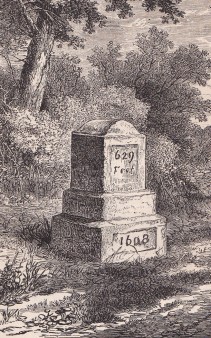

If you follow the Great North Road out of London towards York and Edinburgh you come to the village of Highgate four miles after leaving Smithfield, the traditional starting point of the road. These days you fight your way out through heavy traffic on the A1 along the Holloway Road to a one-way system encircling the Victorian Archway Tavern and next to the Archway Underground stati on. Ahead lies Archway Road running through a deep cutting and spanned after half a kilometre by the bridge carrying Hornsea Lane over the top. If you want to visit Highgate Village itself you need to take the fork off the one-way system just before Archway Road, to drive up Highgate Hill, past the modern Whittington Stone pub and the Whittington Stone itself sitting beside the pavement.

on. Ahead lies Archway Road running through a deep cutting and spanned after half a kilometre by the bridge carrying Hornsea Lane over the top. If you want to visit Highgate Village itself you need to take the fork off the one-way system just before Archway Road, to drive up Highgate Hill, past the modern Whittington Stone pub and the Whittington Stone itself sitting beside the pavement.

If you had been making your way along this route in the mid-14th century you would have no problem with traffic, fumes, noise or jams. But you would have been lurching along a muddy track sunk deep between the fields on either side – the original Hollow Way – until it turned and followed the route of Highgate Hill, for there was no cutting and easy route where Archway Road now runs. You would have armed outriders if you could afford them and a stout cudgel if you could not, because you would be deep in the country here and making your way through an area notorious for footpads or worse.

In the mid 14th century a hermit, William Phelippe, was living in a cell on the lower slopes of Highgate Hill – a great lump of London Clay rising to 423 feet above sea level, a formidable obstacle. William seems to have been that unlikely creature, a wealthy hermit, for he approached the King Edward III with the proposal that he pay for the excavation of gravel from near-by pits and use it to improve the road surface. In return he would set up a toll-bar to tax all wheeled traffic and pack-horses that passed carrying goods. The king duly granted a decree “to our well-beloved William Phelippe, the hermit” who charged two pence per week to each cart with iron-shod wheels, one penny if not iron-shod. Pack horses were charged one farthing a week.

It was north along this improved road that young Dick Whittington, a poor apprentice who had failed to make his fortune in London, was trudging one day, with, so legend tells us, his cat. He paused near to where the Whittington Stone now stands, to rest before tackling Highgate Hill and there he heard the bells of the City calling, “Turn again Whittington, thrice mayor of London.” So he did, and made his fortune and the rest is the stuff of traditional tales and modern pantomime.

But Richard Whittington did exist – he was Lord Mayor in 1397, 1406 and 1420, he was knighted, he was one of the richest men of his time and a notable philanthropist whose charities are still in existence. A succession of Stones has marked the spot – the current one was erected in 1821. The etching above shows the previous version, dated 1608.

By the late 18th century Highgate was a prosperous village with a tollgate on the Great North Road and a good coaching and posting trade, for all the traffic still had to climb the hill and go down its main street at the summit. It was a popular place for early commuters, amongst them Grimaldi the clown who was robbed on the hill by footpads in 1807 returning home from performing at Sadler’s Wells theatre. Fortunately when the thieves saw his pocket watch with his portrait in costume painted on the dial they apologized profusely and returned it!

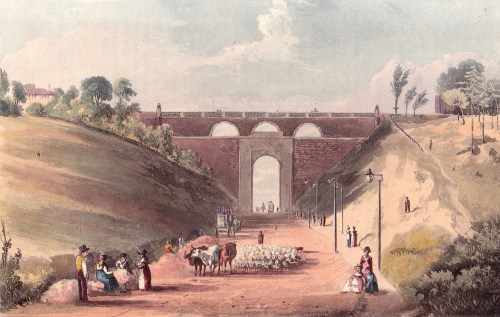

But the increase in coaching traffic meant something had to be done about the hill. Ackermann’s Repository (November 1822) records that, “At Highgate-Hill, over which one of the great north roads branches from the metropolis, a formidable steep presents itself, and which, until about ten years ago, was endured, but liberally abused, by the sufferers obliged to pass it.”

First, attempts were made to tunnel through it but the tunnel collapsed in April 1812, fortunately after the workmen had left at the end of the working day. The tunnel was abandoned and a great cutting driven through, bridged by a massive archway designed by John Nash to carry Hornsea Lane. It took up a considerable width of the carriageway and was eventually replaced in 1900.

The new Archway Road was cut through on the eastern side of the old Archway Tavern which can be seen with the tollgate to the right in the black and white engraving at the top of the post. This is dated in Old And New London as 1825, but trying to accurately date the prints I have of the Archway is a nightmare.

The small rectangular coloured one above is from the Repository (1822) and shows the view beyond the tollgate. But the two rectangular images below are much more problematic if compared to the black and white one . They are two sides of a very large print that was too big to go in my scanner so the unfortunate cow in the middle has lost its hindquarters, I’m afraid.

. They are two sides of a very large print that was too big to go in my scanner so the unfortunate cow in the middle has lost its hindquarters, I’m afraid.

One shows the Archway Tavern which, oddly, has lost the upper part of the right-hand wing which is clearly illustrated in the black and white print. Highgate Hill goes off to the side and the pond, which is shown in the black and white print as walled, has no wall. The other side shows Holloway Road coming in from the right and the tollgate before Archway Hill.

shows Holloway Road coming in from the right and the tollgate before Archway Hill.

To the right just beyond the tollgate is a neo-Gothic building which, according to my early Victorian Ordnance Survey maps, is the Whittington College almhouses, one of Dick Whittington’s charities. The almshouses were moved to this site in 1809 but the neo-Gothic building was not erected until 1822 which means that the black and white print must have been made before that date. This print is an 1823 re-working of an 1813 print which has been changed to show the new almshouses. There’s an image of the original version on the Government Art Collection website.

It is difficult to reconcile this largely rural, village scene with the urban chaos on this site now – I doubt very much that Dick Whittington would have been able to hear the bells and hs cart would have probably been run over by a passing delivery van!

Filed under Buildings, Transport and travel

Jane Austen Visits Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is one o f the most recognisable London landmarks, a major tourist destination redolent with history, yet it is a relatively modern feature, only about 175 years old.

f the most recognisable London landmarks, a major tourist destination redolent with history, yet it is a relatively modern feature, only about 175 years old.

If Jane Austen were to find herself in Trafalgar Square today, I wondered, would she recognise anything at all? There are, in fact, only two landmarks she would be familiar with and one is the statue of Charles I which stands at the western end of the Strand looking down Whitehall to his place of execution. It was the work of Hubert Le Sueur in 1633 but was not erected here until 1675 after a perilous time buried to avoid being melted do wn by the Parliamentarians. Eventually it was purchased by Charles II and the pedestal was designed by Christopher Wren. You can see it here in this print from Ackermann’s Repository (1811) which looks eastward down the Strand.

wn by the Parliamentarians. Eventually it was purchased by Charles II and the pedestal was designed by Christopher Wren. You can see it here in this print from Ackermann’s Repository (1811) which looks eastward down the Strand.

The other landmark she would be familiar with is the church of St Martin in the Fields (built 1722-6) which is clearly recognisable in another Ackermann print of 1815. If Jane stood on the steps, what would she have seen?

The road was called St Martin’s Lane, as it is now, but the buildings on the left of the picture formed a frontage to the vast St Martin’s Workhouse which covered the space now occupied by the National Portrait Gallery.

Directly in front of her would have been a jumble of small buildings and lanes and then the yard of the Queen’s Mews. The King’s Mews occupied the site of the National Gallery.

The royal mews for falcons, horses and carriages, along with lodgings for grooms, and all the associated workers, had been here since the reign of Edward I . The name of nearby Haymarket is explained by the huge requirements for fodder and bedding. William Kent rebuilt the main stable block in 1732 and a detail from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London shows something that looks more like a palace for horses than a stables.

The land sloped to the south – the flatness of the square is due to terracing by Charles Barry in 1840 – and around the mews other buildings grew up like coral on a reef. Many of the buildings were let to private individuals for lodgings or shops, there was a menagerie, a store for public records and in the south-west corner, facing onto Cockspur Street, was the Phoenix fire engine, ready to gallop off to deal with fires – provided the buildings bore the mark of the phoenix showing that they had been insured with the company.

The most notable inn in the area was the Golden Cross, a major coaching establishment with a large yard. It lay under what is now South Africa House at the point where Strand meets Trafalgar Square.

Opposite was Northumberland House which can be seen in the print showing the Charles I statue. It was built in the 17th century for the Earl of Northampton before passing into the hands of the Percy family – the earls of Northumberland. Despite its antiquity and splendour it was demolished in 1874. The site now lies between Craven Street and Northumberland Avenue.

The area would have remained much as Jane Austen knew it until 1830 when demolition began to create John Nash’s Charing Cross Improvement Scheme. The National Gallery was built 1833-7 and includes one feature Jane must have seen in her lifetime but may not have recognised again – pillars from the recently-demolished Carlton House. Nelson’s Column was erected between 1839-43 and the statue added in 1843. The fountains and basins came next in 1845 (remodelled in 1939) and the four lions arrived in 1867.

The National Gallery

So what would Jane have made of the changes? Probably she would be most upset by the disappearance of Spring Gardens just to the south of the square and now under Admiralty Arch. Once the home to picture galleries that she visited and charming tea shops and amusements, it now survives as a few yards of truncated street, a sad relic of Jane Austen’s London.

Filed under Buildings

Take the Number 23 Bus Into History

My favourite journey through London’s historic streets isn’t from a tourist bus but from the front seat on top of the ordinary number 23 from Liverpool Street  station to Marble Arch. I thought you might like to share the ride with me. If you do decide to try this trip I would recommend starting from Liverpool Street station, perhaps after a morning exploring the fascinations of the Spitalfields area on the other side of the station. The picture on the left shows the bus with the yellow brick of the station reflected above it

station to Marble Arch. I thought you might like to share the ride with me. If you do decide to try this trip I would recommend starting from Liverpool Street station, perhaps after a morning exploring the fascinations of the Spitalfields area on the other side of the station. The picture on the left shows the bus with the yellow brick of the station reflected above it

The 23 comes every ten minutes, and starts at the station, so if you aren’t at the front of the queue and able to run upstairs to claim a front seat then it is worth waiting for the next one and being the first person on. You are right on the edge of the City of London here – Spitalfields was outside the Roman and medieval walls – and we are going to travel through every era of London’s history from the Romans to the present day.

The bus sets off down Old Broad Street (a Roman street), crosses London Wall (no prizes for guessing what that’s on the line of) and takes a slight bend to the left, just before Turnbull & Asser’s shop – if you look to the right you’ll see Austin Friars, the reminder of a large Augustinian monastery on the site. Now we turn right into Threadneedle Street (a reference to either the Company of Needlemakers or the Merchant Taylors) with the Royal Exchange on the left and the Bank of England (1788) ahead on the right. The Royal Exchange is the Victorian rebuilding of the trade centre that has flourished here since Tudor times. This is a great place to get off on another day for exploration on foot – the George & Vulture tavern, the Monument, the Bank of England Museum and London Bridge are all close by.

Ahead to the left is Mansion House, official residence of the Lord Mayor of London (not to be confused with the Mayor of London!) since 1752. We pass Mansion House and turn down Queen Victoria Street, one of the later 19th century roads driven through the tangle of medieval streets, whose pattern is fossilised from before the Great Fire. On the left, deep underground, are the remains of the Roman Temple of Mithras, to the right you can catch a glimpse up Watling Street – a Roman road – of St Paul’s Cathedral. (Photo left) We pass the church of St Mary Aldermary and turn left into Cannon Street (the name is a corruption of Candelwrithe Street, a reference to 12th century candlemakers) which leads into St Paul’s Churchyard. Ever since the Middle Ages this area around the cathedral was full of shops, especially book shops, book binders and printers, and that tradition survived even after the Great Fire when Sir Christopher Wren’s great new church rose from the ashes. Jane Austen’s newly-orphaned father George was sent here to live with his uncle Stephen at his shop at “the sign of the Angel and Bible.” George later wrote that he was received “with neglect, if not with positive unkindness.”

(Photo left) We pass the church of St Mary Aldermary and turn left into Cannon Street (the name is a corruption of Candelwrithe Street, a reference to 12th century candlemakers) which leads into St Paul’s Churchyard. Ever since the Middle Ages this area around the cathedral was full of shops, especially book shops, book binders and printers, and that tradition survived even after the Great Fire when Sir Christopher Wren’s great new church rose from the ashes. Jane Austen’s newly-orphaned father George was sent here to live with his uncle Stephen at his shop at “the sign of the Angel and Bible.” George later wrote that he was received “with neglect, if not with positive unkindness.”

If you look out to the left you will catch glimpses of the Thames and it is also fun to spot the street names that go back to the pre-Reformation Catholic past of the area – Ave Maria Lane, Godliman Street, Creed Lane, Pilgrim Street. The bus passes the cathedral (also the site of a Roman temple) and dives down Ludgate Hill towards the valley of the River Fleet. Look out on the right, just after St Martin’s church, for the Old Bailey, leading to the site of Newgate Prison, now under the Central Criminal Courts. The triangular area in front preserves the shape of the area where public hangings were carried out when they were transferred from Tyburn, the end of our journey today. The area immediately to the south, being redeveloped at the moment, was the location of the Belle Sauvage inn, one of London’s oldest and a major coaching terminus. Look up Limeburner Lane immediately after this building site – the curve of the buildings reflect the shape of the walls of the Fleet prison. The picture below shows Ludgate Hill.

When you reach the bottom of Ludgate Hill you would originally have been on the Fleet Bridge crossing the open stream. Gradually it was covered over but it still runs beneath the street, as do all the ancient rivers of London. To your left New Bridge Street runs down to Blackfriar’s Bridge (1769), with the site of the Bridewell prison on its west side, and if you look up to the left you will see the “wedding cake” spire of St Bride’s church, reputedly the building that inspired a local pastrycook to create what became the modern wedding cake.

Now we are climbing out of the Fleet valley up Fleet Street, one of medieval London’s major thoroughfares and once centre of the publishing and newspaper industry. Look out on the right for Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, a seventeenth and eighteenth century tavern frequented by Dr Johnson. Ahead on the right you can see the clock of St Dunstan’s church protruding out over the street (church tower in photo below with Royal Courts of Justice behind). Almost opposite this, at number 32, John Murray, Jane Austen’s publisher, had his offices. He was there until 1812 when he moved to fashionable Albemarle Street, Mayfair. Just past this look out for the Inner Temple Gateway (1610), a survivor of the Great Fire which stopped just short of it.

In the middle of the road is the Temple Bar monument, with the City of London’s griffin roaring defiance at the City of Westminster which begins just the other side. Even the monarch, on state occasions, will stop at the Bar and be greeted by the Lord Mayor before proceeding. Temple Bar itself was moved in the 19th century as a traffic hazard and is now in St Paul’s churchyard.

The Royal Courts of Justice (1880s) loom on your right but keep a sharp look-out to the left as the bus passes to the left hand side of St Clement Dane’s church. Twining’s tea shop occupies a narrow site here with the oldest surviving shop front in London (1787). You can see two Chinese gentlemen (no Indian tea in those days) over the doorway. Jane Austen was often asked by her mother to buy tea here when she was in London, or to pay the bill. In 1814 she wrote to her sister, “I suppose my Mother recollects that she gave me no Money for paying Brecknell & Twining; & my funds will not supply enough.”

We are driving along Strand now, an 11th century street originally on the river bank or strand. We pass St Mary le Strand (location in the 17th century of the first hackney carriage stand ) and come to Somerset House on the left. It dates back to the mid 16th century and was a royal house in the 17th century. By the time Jane Austen knew it the Royal Academy, the Royal Society, the Society of Antiquaries and the Navy Board all occupied wings.

We pass the turning down to Waterloo Bridge (1817) and continue along Strand. All the pre-Victorian buildings have gone now, but just past the Savoy Hotel on the left was the Cole Hole Tavern, home to the Wolf Club, founded by actor Edmund Kean, so he said, for men whose wives did not allow them to sing in the bath. Rudolph Ackermann’s famous Emporium was also close by. On the other side of the street, on the site of what is now the Strand Palace Hotel, was the Exeter Change with its many small shops and Pidock’s (later Polito’s) Menagerie. It was located, bizarely, above ground floor level and contained, amongst other live animals, a hippopotomus that Byron said resembled Lord Liverpool, and even an elephant.

Ahead of us now we can see Nelson’s Column, but before we reach Trafalgar Square we pass Charing Cross station on the left. In the forecourt is the Victorian replacement for one of the twelve Eleanor Crosses that stood on this site.  They were erected by King Edward I to mark the places where the funeral cortege of his wife – his chere reine (=Charing) – stopped in 1290. The original cross stood a little

They were erected by King Edward I to mark the places where the funeral cortege of his wife – his chere reine (=Charing) – stopped in 1290. The original cross stood a little  further along where the statue of King Charles I is now, looking down Whitehall towards his place of execution. The Parliamentarians pulled down the old cross in 1647, but when Charles II was restored to the throne he had eight of the regicides hanged drawn and quartered on that spot.

further along where the statue of King Charles I is now, looking down Whitehall towards his place of execution. The Parliamentarians pulled down the old cross in 1647, but when Charles II was restored to the throne he had eight of the regicides hanged drawn and quartered on that spot.

We skirt the southern edge of Trafalgar Square, developed in 1840 from the chaos of the royal mews, inns, barracks and shops. To our left we can look down Whitehall to Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament and through Admiralty Arch down the Mall to Buckingham Palace. Across the Square is the National Gallery (some of the pillars were reused when the Prince Regent’s Carlton House was demolished) and St Martin in the Fields. The bus will leave the Square by Cockspur Street. Look out to your left for an unprepossessing alleyway, Warwick House Street. Once this terminated in Warwick House, home of the Regent’s daughter Princess Charlotte. He tried to separate her from her mother, his estranged wife Caroline, but one day Charlotte sneaked out of the house and fled down to Cockspur Street where she took the first hackney carriage and fled to her mother.

We skirt the southern edge of Trafalgar Square, developed in 1840 from the chaos of the royal mews, inns, barracks and shops. To our left we can look down Whitehall to Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament and through Admiralty Arch down the Mall to Buckingham Palace. Across the Square is the National Gallery (some of the pillars were reused when the Prince Regent’s Carlton House was demolished) and St Martin in the Fields. The bus will leave the Square by Cockspur Street. Look out to your left for an unprepossessing alleyway, Warwick House Street. Once this terminated in Warwick House, home of the Regent’s daughter Princess Charlotte. He tried to separate her from her mother, his estranged wife Caroline, but one day Charlotte sneaked out of the house and fled down to Cockspur Street where she took the first hackney carriage and fled to her mother.

We pass the foot of Haymarket – home to the market selling, amongst other things, hay and fodder for London’s thousands of horses. It was also notorious for its prostitutes – Haymarket Ware. The bus crosses Waterloo Place and turns up Regent Street. Behind us is the Duke of York’s Column, overlooking St James’s Park. All along that side of Pall Mall stretched Carlton House, once intended to be the culmination of Nash’s dramatic Regent’s Street redevelopment begun in 1816. But Carlton House was demolished in 1826 after the Regent became George IV and moved into Buckingham Palace. All Nash’s original buildings have been replaced as the requirements for modern shops have changed, but the scale and the style remains much as he envisaged. The new street cut though London, separating the squalor of Soho to the east from the riches of fashionable Mayfair to the west.

At Piccadilly Circus – always an awkward shape – we continue up Regent Street to Oxford Circus and turn left into Oxford Street. In the late 18th and 19th centuries it already had a name as a major shopping destination and, as Ackermann’s Repository had it, was “allowed to be one of the finest streets in Europe.” Only one feature remains that is older than the late 19th century and that is one pillar of the entrance to Stratford Place and, as I write, it is shrouded in a protective box while works on Bond Street tube station are carried out.

At Piccadilly Circus – always an awkward shape – we continue up Regent Street to Oxford Circus and turn left into Oxford Street. In the late 18th and 19th centuries it already had a name as a major shopping destination and, as Ackermann’s Repository had it, was “allowed to be one of the finest streets in Europe.” Only one feature remains that is older than the late 19th century and that is one pillar of the entrance to Stratford Place and, as I write, it is shrouded in a protective box while works on Bond Street tube station are carried out.

But one very ancient feature of Oxford Street can still be experienced from our position on top at the front of the bus, and that is the valley of Tyburn Brook which crossed Oxford Street on its way south. On foot you hardly notice it, on the bus it is a definite dip, just where the entrance to Bond Street tube station is. We climb up the other side and continue along to Marble Arch where I suggest leaving the bus. This is the location of the Tyburn gallows, notorious place of public execution, and also of Tyburn turnpike gates marking one of the main entrances into London from the west. From here you can stroll south-east into Mayfair or into Hyde Park – the very edge of Regency London.

On the left is a print from Ackermann’s Repository showing the view eastwards along Oxford Street from the Tyburn turnpike gates. Hyde Park is to the right.

On the left is a print from Ackermann’s Repository showing the view eastwards along Oxford Street from the Tyburn turnpike gates. Hyde Park is to the right.

Happy exploring!

Filed under Buildings, Transport and travel

De-Coding Coade Stone

“Everybody knows” three things about Coade Stone, the artificial stone that decorated so many buildings and monuments in the Georgian and early Victorian period and which survives today in remarkably good condition. Firstly it was invented by Eleanor Coade who ran the business, secondly that the secret recipe for it is lost and thirdly that the works are under the site of the Festival Hall on the south bank of the Thames, just north of Westminster Bridge. Actually, none of these facts are entirely true.

There were two Eleanors – mother and daughter – and both seem to have been extraordinary and independent businesswomen, Eleanor senior was born in 1708 in Dorset and married George Coade who died in 1769. A year after George’s death Daniel Pincot opened an ‘Artificial Stone Manufactory’ by the King’s Arms Stairs, Narrow Wall, Lambeth. He made no claim to have invented the ‘stone’ and he did not patent it. It may have been the same product, or very similar, to the artificial stone and marble that Thomas Ripley took out patents for in 1722. Ripley also operated in Lambeth but went out of business shortly after 1730.

It is unclear whether Pincot opened the factory and then sold it very soon afterwards to Eleanor snr., or whether he was acting as her agent all along, but Pincot vanishes from the scene and Eleanor took her nephew, John Sealy, as her partner. Eleanor never refered to the product as Coade stone but as ‘Lithodipyra’, which means ‘twice-fired stone’ – a clue to how it was made, as a ceramic.

Eleanor snr. died in 1796, aged 88 and was buried in Bunhill Fields in an unmarked grave. Her daughter Eleanor jnr. (b.1732) took over the business, still in partnership with her cousin John Sealy.

The manufactory is shown on Horwood’s map of London north of Westminster Bridge close to King’s Arms Stairs. The small landing stage and steps led up from the foreshore to College Street and thence into Narrow Wall, a winding street which formed a demarcation between fields and scattered cottages and the industrial zone of timber yards, breweries and coal yards that fringed the river. The entire area has disappeared under the site of the Festival of Britain exhibition and the factory was actually under what is now Jubilee Gardens to the south of the Festival Hall.

Excavations when the site was being prepared for the Festival revealed a granite grindstone for preparing the ingredients and various moulds. Once the items were cast they were fired in a muffle furnace.

In 1800 Eleanor jnr. opened an exhibition gallery where Narrow Wall meets Westminster Bridge Road and Horwood’s map shows ‘Coade Row’ at that point. A catalogue of the wares of ‘Coade and Sealy’ from the previous year lists an entire range of architectural ornaments and monuments, including items designed by artists of the calibre of James Wyatt and Benjamin West.

Eleanor jnr. never married, although all references to her are to ‘Mrs’ Eleanor Coade. Her cousin John Sealy died unmarried in 1813 (buried, with a Coade stone memorial, in St Mary’s Lambeth), leaving the substantial sum of £7,500 to his unmarried sister. Eleanor, who was then in her 80s, took on a cousin by marriage, William Croggan, and it was he who carried on the business after her death in 1821, moving the business to Belvedere Road close by.

William Croggan passed the business to his son, also William, who finally closed it down in 1837. The factory was taken over by a manufacturer of terracotta and scaglioni wares but production of Coade stone ceased.

Over six hundred surviving examples of Coade stone are known and they can be found on buildings, as garden ornaments and in churches throughout the country. The Britannia Monument, Great Yarmouth, Norfolk; Captain Bligh’s tomb and the façade of the Royal Society of Arts building in the Adelphi are made from it as is the monumental lion (13 foot long), once on top of the Red Lion Brewery and now on Westminster Bridge. Coade stone was also used in Buckingham Palace, the Brighton Pavilion, Castle Howard and by landscape gardeners such as Capability Brown.

The Britannia Monument to Lord Nelson at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk. The figures at the top are in Coade stone

The ‘secret’ formula is now known, thanks to modern analytical methods. If you want to have a try all you need are a mixture of 10% grog (finely crushed kiln waste); 5-10% crushed flint; 5-10% fine quartz or sand; 10% crushed glass; and 60% ball clay (from Eleanor’s native Dorset). Grind, mix, mould and fire at over 1,000 degrees Centigrade for four days and you will have your very own Coade stone ornament. Possibly best not to try this at home!

If you’ve got a favourite Coade stone memorial or building, I’d love to hear about it.

Filed under Buildings, Science & technology, Women

Soho House – and some very early central heating

A quick word to say that if you were interested in the last post about lighting you might like to see more of the house where I photographed two of the lamps – Soho House in Birmingham. It was the home of pioneer industrialist Matthew Boulton, a meeting place of the famous Lunar Men and the location of what may well be the first hot air central heating system since the Romans! More about it, plus some pictures at http://historicalromanceuk.blogspot.co.uk/

Filed under Buildings, Science & technology

Henry at Whites! Oh, what a Henry!

St James’s Street was the heart of fashionable masculine London during the late Georgian and Regency period. Here gentlemen had their lodgings, kept their mistresses, bought their clothes and gambled in hells and clubs. It was not an exclusively male preserve, for modistes had their shops there and ladies could even buy ready-made corsets from Mrs Clark, whose shop was at no.56, and who advertised in 1807 ‘…a large assortment of corsets of every size, and superior make, so that ladies may immediately suit themselves without the inconvenience of being measured.’

St James’s Street was the heart of fashionable masculine London during the late Georgian and Regency period. Here gentlemen had their lodgings, kept their mistresses, bought their clothes and gambled in hells and clubs. It was not an exclusively male preserve, for modistes had their shops there and ladies could even buy ready-made corsets from Mrs Clark, whose shop was at no.56, and who advertised in 1807 ‘…a large assortment of corsets of every size, and superior make, so that ladies may immediately suit themselves without the inconvenience of being measured.’

However, it for the clubs that St James’s Street is famous and you can still view the exterior of many of them – getting inside is another matter! Membership has always been exclusive: who you knew mattered, breeding mattered – but money mattered less. Politics might influence which clubs a gentleman felt most at home in, although White’s, the most exclusive of them all, was non-political.

However, it for the clubs that St James’s Street is famous and you can still view the exterior of many of them – getting inside is another matter! Membership has always been exclusive: who you knew mattered, breeding mattered – but money mattered less. Politics might influence which clubs a gentleman felt most at home in, although White’s, the most exclusive of them all, was non-political.

Boodles attracted the country set and hunting squires, the Four in Hand, sporting gentlemen. The Travellers’ Club was favoured by diplomats, Watier’s, in Piccadilly, by lovers of fine food and the Roxburghe was the haunt of bibliophiles. If you wanted high-stakes gaming, then Brookes’s and, after 1827, Crockford’s were the clubs for you.

Today, if you walk down St James’s Street from the top of the hill at Piccadilly you almost immediately come to Crockfords on your right and White’s on your left. White’s possessed the famous Beau (or Bow) Window where the elite would sit to view, and pass judgment on, the passing scene. It still has a bow, but, given that there have been some changes to the exterior during the 19th century, it may not be the famous one.

Henry Austen, Jane’s banker brother, had some very respectable connections, but he was not a club man. However, he must have had connection with those who were. In 1814, after the first defeat of Napoleon, threw a great ball that cost £10,000. Guests included King George III, the Prince Regent, the Emperor of Russia – and Henry Austen. ‘Henry at Whites! Oh! What a Henry.’ Jane could hardly contain herself at the news.

A little further down on the same side of the road is Boodles club. It moved here to no.28 in 1783 to premises originally occupied by the Savoir Vivre, a notorious hell.

To reach Brooks’s, you need to cross the road. Do take advantage of one of the traffic islands in this busy, very wide, street – they were originally introduced in the early nineteenth century to make life safer for the slightly inebriated clubmen making their way from one establishment to another. Brook’s is on the corner of Park Place and was one of Byron’s clubs. A stronghold of the Whigs, it moved here in 1778. this is the one London club I have been inside and the Great Subscription Room, illustrated here, looks just as it did then (although there were no Regency bucks engaged in gambling, much to my disappointment!).

Just a little further down was Arthur’s (not a great success) and the Cocoa Tree coffee house. The Cocoa Tree was not a formal club, but provided another sanctuary for like-minded gentlemen, such as Byron, who frequently visited.

Just a little further down was Arthur’s (not a great success) and the Cocoa Tree coffee house. The Cocoa Tree was not a formal club, but provided another sanctuary for like-minded gentlemen, such as Byron, who frequently visited.

Finally, to see the location of one of the gaming ‘hells’ where almost anyone who had the money to bet was admitted, cross the road again and walk down to the narrow entrance just before Berry Bros. & Rudd. This leads to Pickering Place, now a charming little courtyard, but once the home of some notorious hells, the reputed location of the last duel in London and, later in the 19th century, the home of the Texas legation.

Top: a club interior. The young man in breeches and carrying a riding whip and hat is being reproved for being improperly dressed.

Second: the bow window outside White’s Club (looking up towards Piccadilly)

Third: The handsome frontage of Boodles’s Club

Bottom: one corner of the Great Subscription Room at Brooks’s Club (1808). A high-stakes game is underway with a large pot of money to be won in the hollowed-out table centre.