Few tourists walking up Ludgate Hill towards St Paul’s Cathedral today realise that they are close to three of the major London prisons, but the Bridewell, the Fleet and Newgate are within a stone’s throw.

Coming up New Bridge Street from Blackfriars’s Bridge you are walking over the Fleet River (or Ditch as it had become by the time of Roque’s map in 1747) and passing, on your left, the site of the Bridewell, or as it was known in cant terms, the Mill Doll or the Old Doss. It was built on the site of Henry VIII’s Bridewell Palace (the place where Holbein’s famous painting of The Ambassadors was created). In 1553 Edward VI gave the palace to the City as a refuge for homeless children, but in 1556 it became a House of Correction and workhouse. It dealt with vagrants, beggars, paupers and petty offenders until it burned down in the Great Fire of London, 1666.

It was rebuilt and, because it was dealing with petty crime, handled a very large number of prisoners – 1,989 committals in 1800, for example. Its medical facilities were considered excellent by the standards of the day and it did give some training to youths and care to the babies born there to unmarried mothers. The image of 1808 shows the ‘Pass-room’ for unwed mothers, each with her bed of straw. The sign on the wall reads ‘Those who Dirts Their Bed shall be Punished.’ The Bridewell closed in 1855 and most of it was demolished, although you can still see part of the handsome façade just south of Costa Coffee.

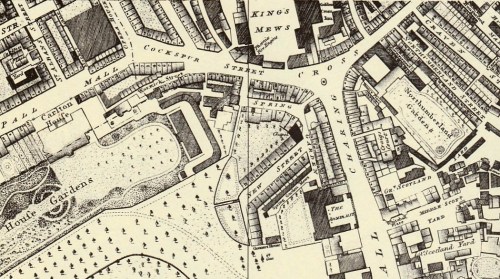

When you reach the crossroads, with Ludgate Hill to your right and Fleet Street to your left, you are at the site of the Fleet Bridge. In front of you now is Farringdon Street, but this used to be Fleet Market, with the Fleet Ditch paved over and a long line of market stall running north. William Morgan’s map of 1682 shows the Fleet running open here in a canal.

In the angle between the Fleet and the northern side of Ludgate Hill was the Fleet Prison. As a pun on its name its Warden became known as Commander of the Fleet and the prison itself as ‘the Navy Office.’ The site of the Fleet Prison resembled a strange letter P and, as with so many ancient sites in London (it was built in 1197, destroyed during the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, then in the Great Fire and also severely damaged during the Gordon Riots of 1780), the shape remains – walk up Ludgate Hill and look to the left down the relatively new Limeburner Lane and you can see the curve in the modern buildings on the site.

The Fleet was a debtors’ prison , with about 300 held there, often with their families, until they had discharged their debts. Given that they had to pay their gaolers for absolutely everything from food to having their chains removed, it is hard to see how they could do so without outside help. Many were reduced to begging from the windows of the cells, but those with a trade were permitted to exercise it and, if they had a little money, could take lodgings in the area immediately around the prison – the ‘Liberty of the Fleet.’ Before the Marriage Act of 1753 the Liberty was a prime location for secret or hasty marriages – as many as three hundred in a week.

The prison was frequently condemned for its appalling conditions but it did not close until 1842 and it was demolished four years later.

For criminals, prisons were not places of punishment until later in the 19th century when the reduction in hangings and floggings meant that new, less physical, punishments such as a term in prison, were devised. In Georgian times they were holding places for prisoners awaiting trial or punishment – hanging, flogging, transportation, time in the stocks or pillory. They were chaotic, filthy and rife with disease and a prisoner’s degree of comfort, if such a thing was to be had, depended on the ‘garnish’ or bribes they could give to the gaolers, just as happened in the Fleet.

For criminals, prisons were not places of punishment until later in the 19th century when the reduction in hangings and floggings meant that new, less physical, punishments such as a term in prison, were devised. In Georgian times they were holding places for prisoners awaiting trial or punishment – hanging, flogging, transportation, time in the stocks or pillory. They were chaotic, filthy and rife with disease and a prisoner’s degree of comfort, if such a thing was to be had, depended on the ‘garnish’ or bribes they could give to the gaolers, just as happened in the Fleet.

Climb Ludgate Hill a little further and you come on the left to The Old Bailey. In the early 18th century this led to a Sessions House – a place where trials took place and now vanished under the southern end of the Central Criminal Courts (1907). Following Old Bailey north you come to Newgate Street where, just to the right was, literally, the New Gate, a massive gatehouse spanning the road. From its southern part Newgate prison extended under what is now the majority of the Central Criminal Courts site. The first records of a prison here are 1188. It was rebuilt after the Great Fire and again in 1770-8, burned down during the Gordon Riots and rebuilt 1780-3.

Newgate was so notorious that Grose’s and other slang dictionaries give over fifteen names for it – No.9 Fleet Market, Ackerman’s Hotel, the Stone Pitcher and Newman’s Tea Garden amongst them. An original door from Newgate and now in the Museum of London is shown above.

Roque’s map shows the Old Bailey forking just opposite the Sessions House with Little Old Bailey running up to Newgate Street on the left and leaving a triangular block of buildings in the centre.

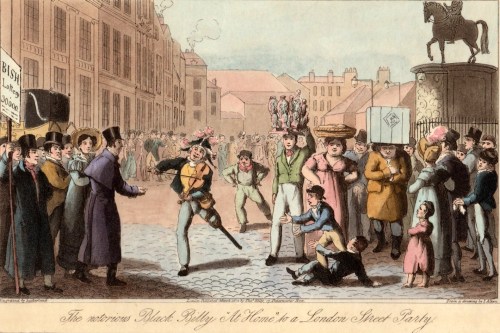

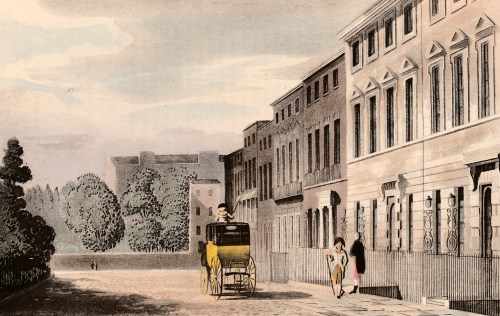

When public hangings at Tyburn were abolished – the long drive across London through jeering and cheering crowds became to be seen as uncivilised, and it certainly disturbed the peace of the smart new developments north of Oxford Street – they were transferred to Newgate in 1783. This was supposed to create a more orderly atmosphere where the watching executions could be experienced with due solemnity. To this end the buildings between the Little Old Bailey and the main street were demolished at the same time as the prison was rebuilt following the Gordon Riots, creating a triangular space which is still open today.In the print above (1814) the Sessions House is on the right with Newgate Prison itself beyond it. The open space faces it, out of sight to the left of the print.

Naturally public executions at the new location were as much of a bear garden as before, with the crowd crammed into the enclosed space and every property with a view making a killing out of renting out window space to view the condemned being led out through the Debtors’ Door.

The print below shows the execution of the Cato Street conspirators, 23 February, 1820. Because they were convicted of treason the initial sentence was hanging, drawing and quartering, a brutal survivor or the middle ages. As a nod to modern times it was commuted to hanging, but the bodies were beheaded symbolically afterwards.

Newgate Prison is seen on the right and the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, where a bell was tolled before a hanging, in the background.

Partly obscured by the cross-beam of the gallows you can just make out a rectangular panel. This was hung with chains and shackles and, when the prison in King’s Lynn was built, that door was reproduced in all its details.

Public hangings were ended in 1868 and now it takes an effort to stand in the attractive space, with its flower tubs and benches,facing the dignified mass of the Edwardian Central Criminal Courts and with the church still standing to your left and imagine what the place must have been like during an execution.

You can find these prisons on Walk 8 of Walking Jane Austen’s London and if you are intrigued by the slang and cant terms for the prisons you can find more for crime and punishment and the whole colourful world of Georgian and Regency underworld and sporting life in Regency Slang Revealed.

Save

Save

Save

Save

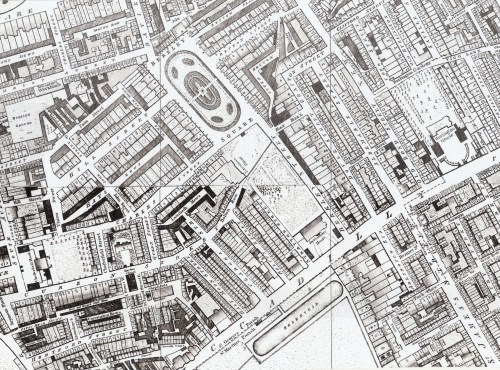

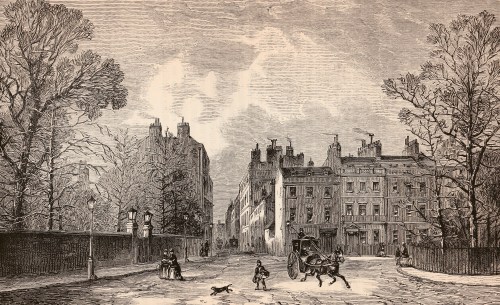

In 1717 the 2nd Earl of Oxford, Edward Harley, began work on the development of his estates north of “the road to Oxford” or Tyburn Road, that eventually became Oxford Street. The first element in his grand design was Cavendish Square, named for his wife Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles. The Duke of Chandos bought the entire northern side for a mansion (described by Ackermann’s as a ‘palace’), Lord Harcourt and Lord Bingley bought sites on the east and west and the rest was sold to speculative builders. Work was interrupted by the financial crisis of the South Sea Bubble in 1720 but the Earl persisted, developing streets and Oxford Market to stimulate interest in his scheme.

In 1717 the 2nd Earl of Oxford, Edward Harley, began work on the development of his estates north of “the road to Oxford” or Tyburn Road, that eventually became Oxford Street. The first element in his grand design was Cavendish Square, named for his wife Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles. The Duke of Chandos bought the entire northern side for a mansion (described by Ackermann’s as a ‘palace’), Lord Harcourt and Lord Bingley bought sites on the east and west and the rest was sold to speculative builders. Work was interrupted by the financial crisis of the South Sea Bubble in 1720 but the Earl persisted, developing streets and Oxford Market to stimulate interest in his scheme. the Bason and the gravel workings to the north had completely vanished under streets and houses and the whole square had been developed as can be seen in the map to the right.

the Bason and the gravel workings to the north had completely vanished under streets and houses and the whole square had been developed as can be seen in the map to the right.

For criminals, prisons were not places of punishment until later in the 19th century when the reduction in hangings and floggings meant that new, less physical, punishments such as a term in prison, were devised. In Georgian times they were holding places for prisoners awaiting trial or punishment – hanging, flogging, transportation, time in the stocks or pillory. They were chaotic, filthy and rife with disease and a prisoner’s degree of comfort, if such a thing was to be had, depended on the ‘garnish’ or bribes they could give to the gaolers, just as happened in the Fleet.

For criminals, prisons were not places of punishment until later in the 19th century when the reduction in hangings and floggings meant that new, less physical, punishments such as a term in prison, were devised. In Georgian times they were holding places for prisoners awaiting trial or punishment – hanging, flogging, transportation, time in the stocks or pillory. They were chaotic, filthy and rife with disease and a prisoner’s degree of comfort, if such a thing was to be had, depended on the ‘garnish’ or bribes they could give to the gaolers, just as happened in the Fleet.