We’ve arrived at that windy season when raising an umbrella is asking for trouble, as this delicious original water colour sketch (unfortunately undated) reminds me.

The interesting thing about this is that the men are using umbrellas, something that they probably wouldn’t have considered before the early 1800s.

Although parasols as protection from the sun date back to the 4th century BC in the Near East, and possibly earlier in China, the idea of using them to hold off the rain appears to be a 17th century innovation in France, Italy and England – but for ladies only. By the mid-18th century continental gentlemen would happily be seen sheltering from a downpour under an umbrella covered in oiled silk and English ladies would routinely use them, but there was a distinct stigma about Englishmen resorting to an umbrella.

Umbrellas were, it seems, ‘French’ and therefore, by definition, an effeminate accessory. Beau Brummell would never carry one, considering that no gentleman should, and advocated taking a sedan chair if there was the slightest risk of rain.

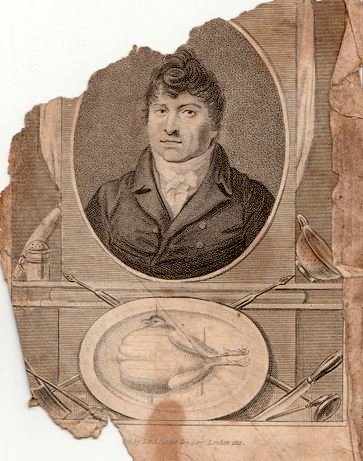

However, some practical men did ignore the jeers, the most well-known of them being Jonas Hanway (1712-1786), a much travelled man, who designed his own, rather large and cumbersome umbrella and persisted in using it. He was verbally attacked by the hackney carriage drivers who saw this as a direct attack on their business but he ignored their threats and one of the slang terms for an umbrella at the time was a Hanway. (The Victorian ‘gamp’ was named after Dickens’s Mrs Gamp, not the other way around.) The below detail from a Victorian imagining of Mr Hanway shows the interest he attracted.

By the early 19th century practicality had won over prejudice for most gentlemen and the use of a rain umbrella became usual for both sexes. In 1814 in Mansfield Park Jane Austen writes of the rescue of a very wet Fanny Price:

“… when Dr Grant himself went out with an umbrella there was nothing to be done but to be very much ashamed and to get into the house as fast as possible; and to poor Miss Crawford, who had just been contemplating the dismal rain in a very desponding state of mind, sighing over the ruin of all her plans of exercise for that morning, and of every chance of seeing a single creature beyond themselves for the next twenty four hours, the sound of a little bustle at the front door and the sight of Miss Price dripping with wet in the vestibule was delightful.”

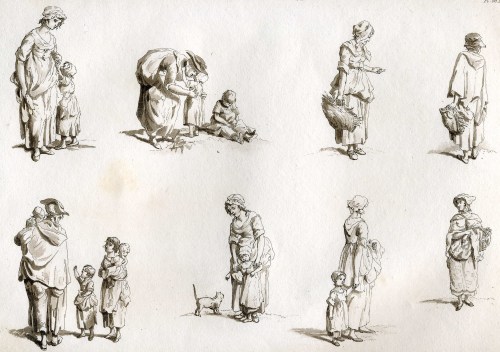

Cruickshank’s delightful series of sketches of various months often show umbrellas. This one (February) has a man using his as a walking aid to negotiate the muddy street while the lady with her skirts hitched up has a far less substantial version.

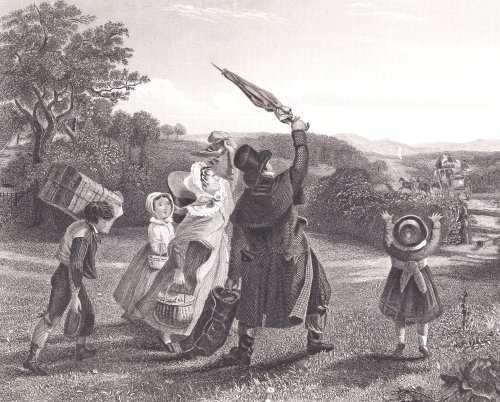

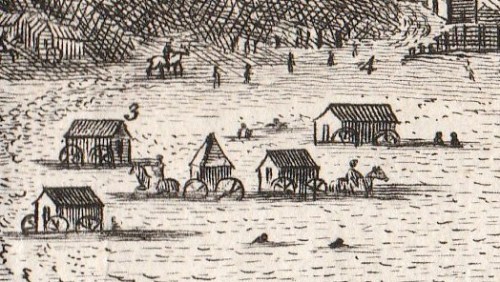

In this undated sketch (a little earlier than the Cruickshank) both men hold umbrellas, although I suspect that the use of one on horseback may just be part of the joke.

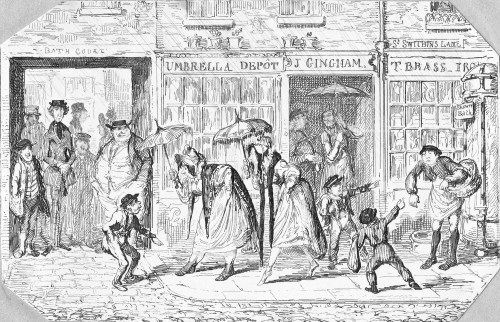

Specialist shops soon started selling umbrellas, as can be seen in another Cruikshank scene which shows one belonging to J. Gingham. The ladies are using what look more like parasols whereas the gentleman inside the shop is having a much more sturdy version demonstrated.

A gentleman travelling by stagecoach might take a umbrella, as can be seen in this image of someone missing the stage –

Of course you had to be considerate in how you used your umbrella. In 1822 Stanley Harris recalls sitting in front of a woman with an umbrella who would “shove it below your hat so adroitly as to send a little stream of water down the back of your neck.” This delightful drawing by Cecil Aldin shows the misery of being on top of the stage in the rain, even with a brolly. But even in this downpour, it is only a female passenger who is using one.

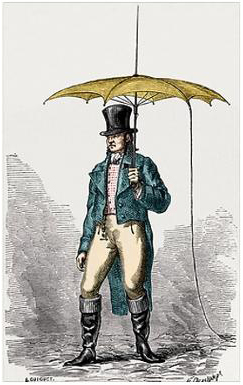

Finally here is a print showing a French invention – an umbrella complete with lightening conductor. Somehow I cannot see any English gentleman consenting to be seen with such an inelegant contraption!

(This is an out of copyright image from Louis Figuier: Les merveilles de la science ou description populaire des inventions modernes (S. 596 ff.) (1867), Furne, Juvet)

As I found when I was researching for my book

As I found when I was researching for my book  at Walton in Warwickshire, now a Landmark Trust property.

at Walton in Warwickshire, now a Landmark Trust property.

Verney.

Verney.

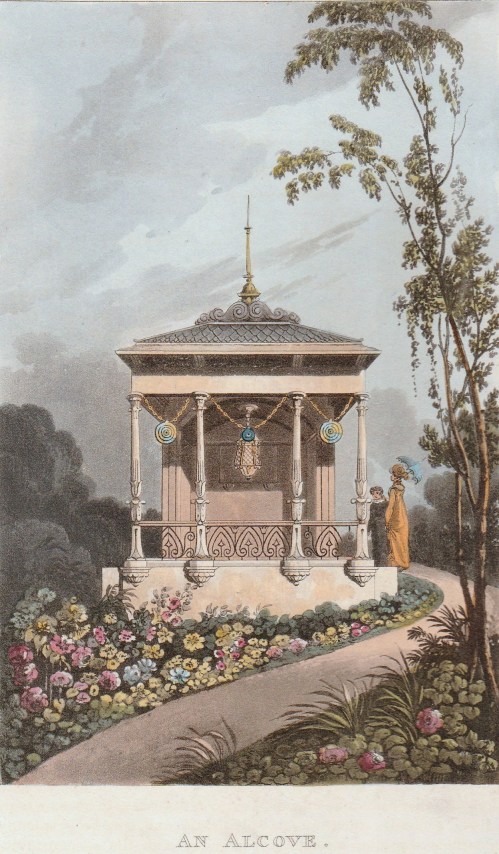

The others? There was The Pigsty (above) overlooking Robin Hood’s Bay – a miniature Classical temple with a spectacular view built by an eccentric farmer in 1891 for some very pampered pigs. You can see the view below:

The others? There was The Pigsty (above) overlooking Robin Hood’s Bay – a miniature Classical temple with a spectacular view built by an eccentric farmer in 1891 for some very pampered pigs. You can see the view below:

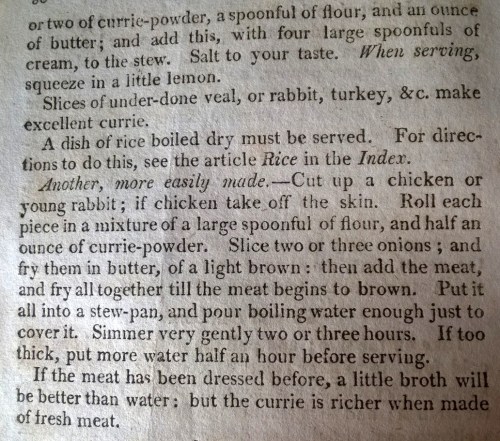

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005).

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005).