I have just bought a bound volume of the Lady’s Magazine for 1815 and was curious to see whether St Valentine’s Day is mentioned. It is, but only in this “Proclamation” by Cupid, addressed “to the Two-penny Postmen, on Saint Valentine’s Day” “From our Court at Matrimony Place, in the Wandsworth Road.”

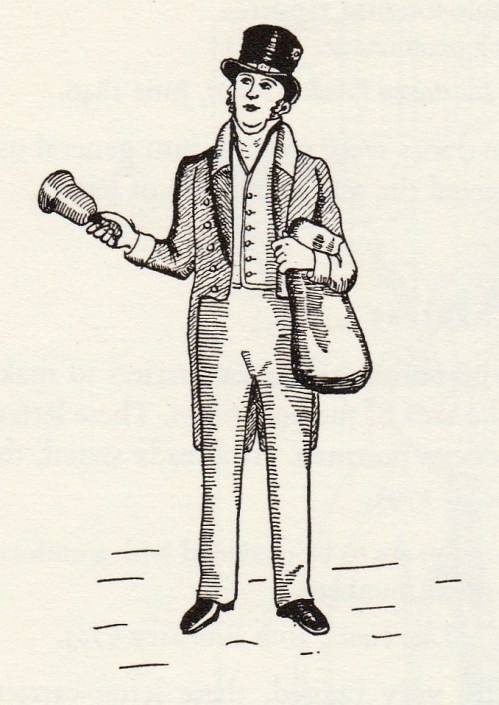

Letter Carrier and Bellman in red cut-away coat with blue collar, black top hat with gold band and cockade, grey waistcoat and trousers. From Cunnington & Lucas: Occupational Costume in England

“Heralds of my fame, on this auspicious morn outstrip the winds in their course; fly to accomplish my wishes, Leave not a cook-maid, a house-maid, or any other maid, from Hyde Park Corner to Whitechapel Church, without the dulcet murmurs of her faithful swain; who, in sending his tributary stanzas, not only soothes the soul of dear Dulcinea, but puts two-pence into the pockets of his majesty’s minsters. Remember that you are the bearers of hearts and darts, of fears and tears, of hopes and ropes, of pains and brains, of eyes and sighs, of loves and doves; of true lovers’s [sic] knots, of Hymen’s altars, and all the vast variety of inventions that fond affection so delights to lay at the feet of some adored object, on this day of days. Remember all this, I say; and if you think any letter you may have, from its paltry sneaking look; from it not being hot-pressed, wire-wove and gilt edged; or from its want of a kiss dropped in wax on the envelope, relates only to some petty affair of business, put it in your pocket to be delivered at your leisure, or not at all if you please; and hasten to deliver all those that relate to love and me, with the light foot, and the bounding speed of the mountain deer.

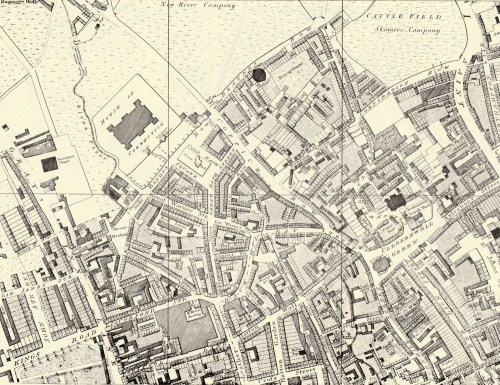

Ye mounted post-lads that amble on bony nags to all the environs of this great city, spare not the spur on this day of love; wear out your whips my boys, on the lank sides of your Rosinantes; be utterly careless as to whom you may cover with mud in your career of fame; emulate the never-to-be-forgotten Johnny Gilpin of Cheapside memory, and lay the dirt about you “on this side and on that”; for, oh think, some dairy-maid at Enfield, some bar-maid at Islington, some thresher of corn at Highgate, some turnpike-man at Bow, may be dying with expectation of the promised or expected Valentine.

Do this, ye letter-bearers, as ye hope for my favor. Do this, and I will prosper all your affairs of love; not a postman shall pine; but from my influence all the respective fair ones, of whom they may chance to be enamoured, if they offer marriage, shall embrace them and their offers together. But tremble if you disappoint me! The ceaseless sigh of love shall be your’s [sic]; I will make your hearts heavier than your bags of new halfpence are, since the old ones are laid aside; I will make all those females ye shall be in love with, cruel and flinty-hearted, til they shall drive you to despair, and suicides among the tribe of two-penny postmen be as common as a fog in November, or a cutting wind in March.

Farewell!”

The Two-penny Post replaced the Penny Post in London following an Act of 1802 which meant that the cost of sending a letter anywhere in the country was a uniform two pence (2d). In 1805 the cost to post a letter to the country rather than a town, went up to 3d leaving the town post at 2d. From the tone of the “Proclamation” (and the snide dig at money going into the pockets of ministers) the increase was still smarting thirteen years later!

From 1773 the postman would have worn a uniform, shown at the top of the post. His brass buttons were inscribed with his personal number. He would ring a bell so you could give him your letters to be posted (a sort of human letterbox, in effect) and he would deliver to the door using the ‘postman’s knock’ a distinctive double blow. There were no stamps as we known them on letters at the time – those came in during Victoria’s reign – and letters might be pre-paid or paid for on receipt.

I am intrigued that Cupid mentions only working women. Would those of the middle and upper classes expect their Valentines to be hand-delivered by their swain or his servant? Or would they coyly pretend they did not indulge in such behavior? And yet Cupid mentions expensive “hot-pressed, wire-wove and gilt edged” writing paper – surely beyond the means of the suitor of a milkmaid or thresher of corn?

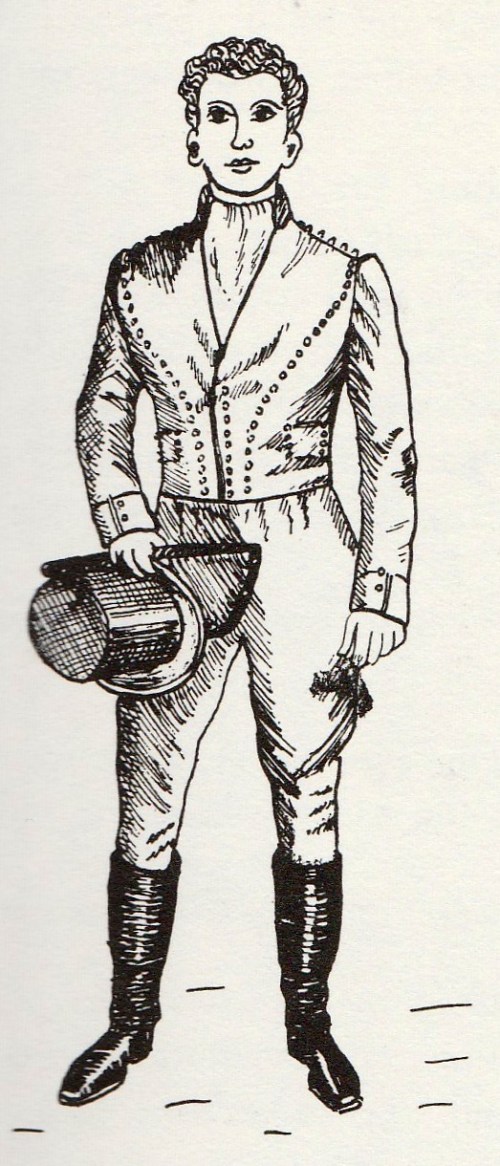

Post boy 1805. His uniform is blue waistcoat with sleeves and brass buttons, buff-coloured breeches, black boots and brown top hat. (From Cunnington & Lucas. Occupational Costume)

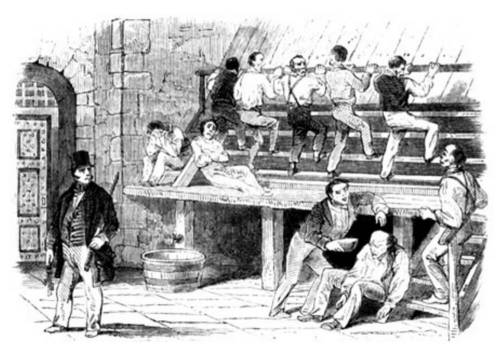

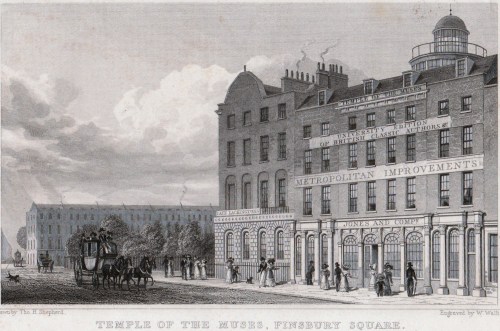

“The edifice, which is of brick, stands within a large area, encompassed by a strong buttressed wall of moderate height. The gate is of Portland stone, contrived in a massy style, and sculptured with fetters, the hateful but necessary appendages of guilt.”

“The edifice, which is of brick, stands within a large area, encompassed by a strong buttressed wall of moderate height. The gate is of Portland stone, contrived in a massy style, and sculptured with fetters, the hateful but necessary appendages of guilt.”

Turkey was not just food for the well-off and middle classes as I discovered when researching for

Turkey was not just food for the well-off and middle classes as I discovered when researching for

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in  I love ice cream – which is fortunate as my husband, who is the cook in our house, has bought an expensive Italian ice cream maker which means we’ve got to eat lots to make it earn its keep!

I love ice cream – which is fortunate as my husband, who is the cook in our house, has bought an expensive Italian ice cream maker which means we’ve got to eat lots to make it earn its keep!

The image above is from La Belle Assemblée for October 1809 and shows ‘Sea Coast Promenade Fashion.’

The image above is from La Belle Assemblée for October 1809 and shows ‘Sea Coast Promenade Fashion.’ Somewhat later – I do not have a date for this, but it is c1820 – is this ‘Walking Dress’ from Ackermann’s Repository. I can’t help feeling that this lady is looking positively shifty as she readies her telescope.

Somewhat later – I do not have a date for this, but it is c1820 – is this ‘Walking Dress’ from Ackermann’s Repository. I can’t help feeling that this lady is looking positively shifty as she readies her telescope.

What did one wear to get to and from those bathing machines? The ever-inventive Mrs Bell produced a magnificent ‘Sea Side Bathing Dress’ for the August 1815 edition of La Belle Assemblée. This is not the costume for entering the sea but for wearing to get there, and it is lavishly trimmed in drooping green, presumably to imitate seaweed. Note the bag she is carrying. This contains Mrs Bell’s ‘Bathing Preserver’ which she produced in 1814. You can see it in its bag again below (La Belle Assemblée September 1814). Here the lady is wearing ‘Sea Side Morning Dress’ with ‘Bathing Preserver. Invented & to be had exclusively of Mrs Bell, No.26 Charlotte Street, Bedford Square.’ The Preserver is in the bag lying beside her chair.

What did one wear to get to and from those bathing machines? The ever-inventive Mrs Bell produced a magnificent ‘Sea Side Bathing Dress’ for the August 1815 edition of La Belle Assemblée. This is not the costume for entering the sea but for wearing to get there, and it is lavishly trimmed in drooping green, presumably to imitate seaweed. Note the bag she is carrying. This contains Mrs Bell’s ‘Bathing Preserver’ which she produced in 1814. You can see it in its bag again below (La Belle Assemblée September 1814). Here the lady is wearing ‘Sea Side Morning Dress’ with ‘Bathing Preserver. Invented & to be had exclusively of Mrs Bell, No.26 Charlotte Street, Bedford Square.’ The Preserver is in the bag lying beside her chair.

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)

Frances was the wife of the Governor of New Hampshire and, as Loyalists, they and many others had been forced to flee by the American forces. Apparently she was very unhappy in Canada, missed her son who was in London and fretted at her diminished social status. An affaire with a prince must have raised her morale considerably! However, her husband wrote to the King to complain and William was recalled to England. (In the painting above of 1765 by John Singleton Copley she was still married to her first husband, Theodore Atkinson. he was her cousin, as was John Wentworth whom she married withing a week of Theodore’s death. Image in public domain.)