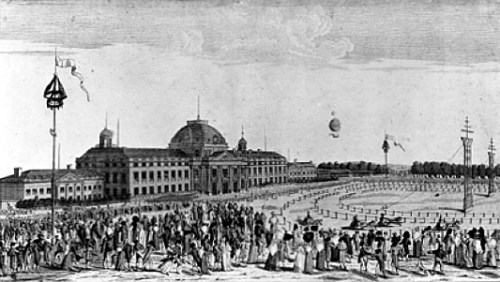

I’m back north of the Border again for today’s blog, visiting an engineering feat by one of Regency Britain’s greatest engineers which, although located in Scottish waters, imust have been a wonder for the entire country. When I was in the delightful little fishing port of Arbroath ( in pursuit of the famous and delicious Arbroath Smokies) I spotted an elegant and unmistakeably Regency building on the shore. It looked like a miniature lighthouse but turned out to be the signalling station for the Bell Rock lighthouse and home to the families of the lighthouse keepers.

Bell Rock is 11 miles (18 km) off the coast at Arbroath and is part of the lethally dangerous Inchcape reef that had proved a major hazard to shipping on this busy coastal route for centuries. In the Middle Ages an abbot had a bell fixed to a floating platform anchored to the reef, which was some warning, but the frequent storms repeatedly destroyed it. The reef is virtually invisible except at low tide when about four foot of it is above the water. Building a lighthouse seemed an almost impossible technical feat, but following the loss of HMS York with all hands in 1806 pressure grew for a solution. In that year a bill was passed through Parliament for a stone tower at a cost of £45,000 to be paid for by a duty on shipping between the ports of Peterhead and Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Two of the greatest engineers of the day were inv olved – John Rennie, who as Chief Engineer, was responsible overall for the project, and Robert Stevenson, who as Rennie’s assistant and the resident engineer, risked his life on the reef along with the workmen. On shore the signalling station allowed communication with the lighthouse and provided a home for the keepers’ families and accommodation for them when they were not on duty. Now it is an excellent little museum all about the Bell Rock and its construction.

olved – John Rennie, who as Chief Engineer, was responsible overall for the project, and Robert Stevenson, who as Rennie’s assistant and the resident engineer, risked his life on the reef along with the workmen. On shore the signalling station allowed communication with the lighthouse and provided a home for the keepers’ families and accommodation for them when they were not on duty. Now it is an excellent little museum all about the Bell Rock and its construction.

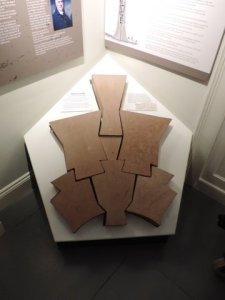

This photograph is of one of the models in the museum showing the difficulties that Stevenson had to overcome to build the lighthouse. First a wooden tower was built to house the men when the tide came in and then, whenever there was low water, they came out onto the exposed reef and worked on the tower itself, building it up with a jigsaw of interlocking stone blocks that had been cut during the winter months when no building could take place on the rock. The ingenious design of the blocks is shown in this model.

Despite the dangers and difficulties the tower was completed in only four years and became operational in 1811. It has been in continuous operation ever since, saving innumerable lives. These days the light is fully automated.

Despite the dangers and difficulties the tower was completed in only four years and became operational in 1811. It has been in continuous operation ever since, saving innumerable lives. These days the light is fully automated.

Robert Stevenson (1772-1850) was educated at a charity school when the death of his father left the family almost destitute. His future career was determined when he was fifteen and his mother married Thomas Smith, a tinsmith, lamp maker and mechanic who was engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board. Robert became his assistant and by the age of nineteen had built his first lighthouse on the River Clyde. Bell Rock is considered his masterpiece, but he was responsible for many other lights as well as roads, bridges, harbours, canals, railways, and river navigations. Three of his sons followed in his footsteps as civil engineers and his grandson was the writer Robert Louis Stevenson.