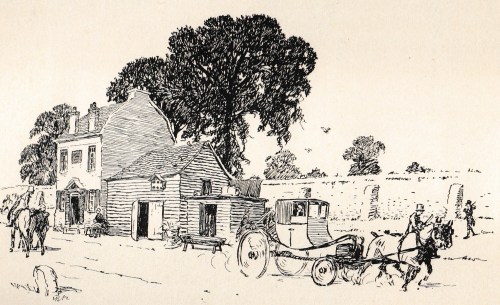

“This square is esteemed the next in beauty, as it is in extent, to Grosvenor-square. It is built with more regularity than the latter: but the very uniformity of the houses, and the small projection of the cornices, are not favourable to grandeur and picturesque effect.”

This modified rapture comes from the beginning of the article in Ackermann’s Repository of August 1813 accompanying this print of the north side of Portman Square.

The square was begun in 1764 as a speculative development by John Berkely Portman, MP, for whom it is named. It rapidly became one of the most fashionable addresses in London and ‘The residence of luxurious opulence,’ according to Priscilla Wakefield, the Quaker philanthropist and writer of children’s non-fiction books.

Amongst its residents was Lord Castlereagh, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, closely associated with Lord Liverpool’s repressive government. The portrait below is after the original by Lawrence. Shelley wrote of him in The Mask of Anarchy,

‘I met Murder in the way –

He had a mask like Castlereagh.’

At the time of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 a furious mob attacked his house and smashed the windows.

Considerably more liberal was Mrs Elizabeth Montagu who lived in the house built for her 1777-82 on the north-west corner, now replaced by the massive block of the Radisson Blu hotel. Mrs Montagu was an intellectual – a ‘blue stocking’ – and philanthropist.

Every May Day she gave a roast beef and plum pudding dinner to chimney sweeps and their apprentices, the unfortunate ‘climbing boys’.

As the Ackermann article reports, these were children “doomed to a trade at once dangerous, disagreeable, and proverbially contemptible, the chimney-sweepers.”

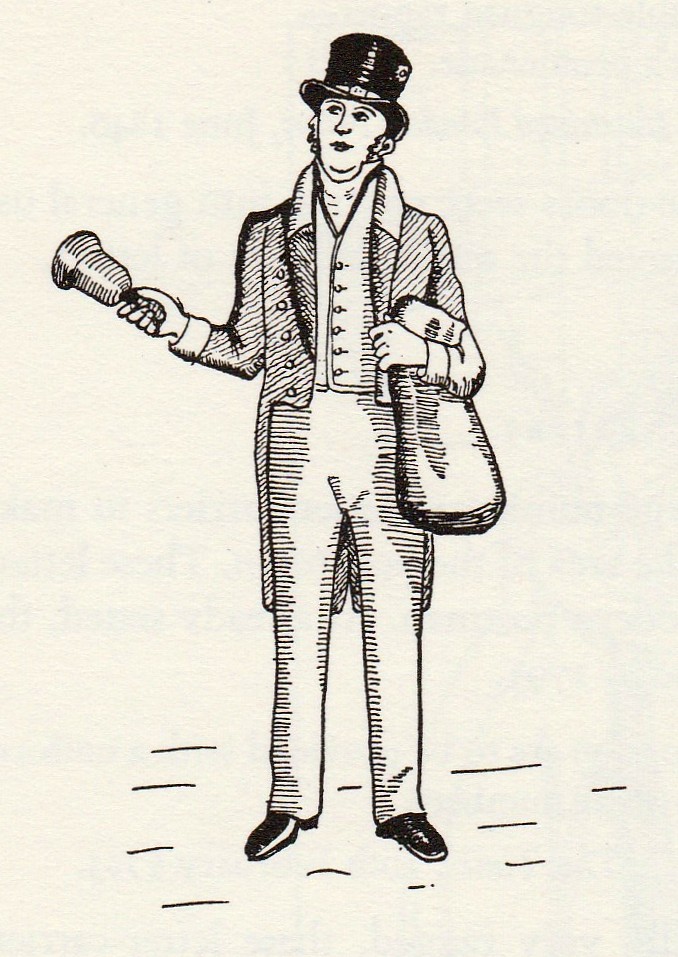

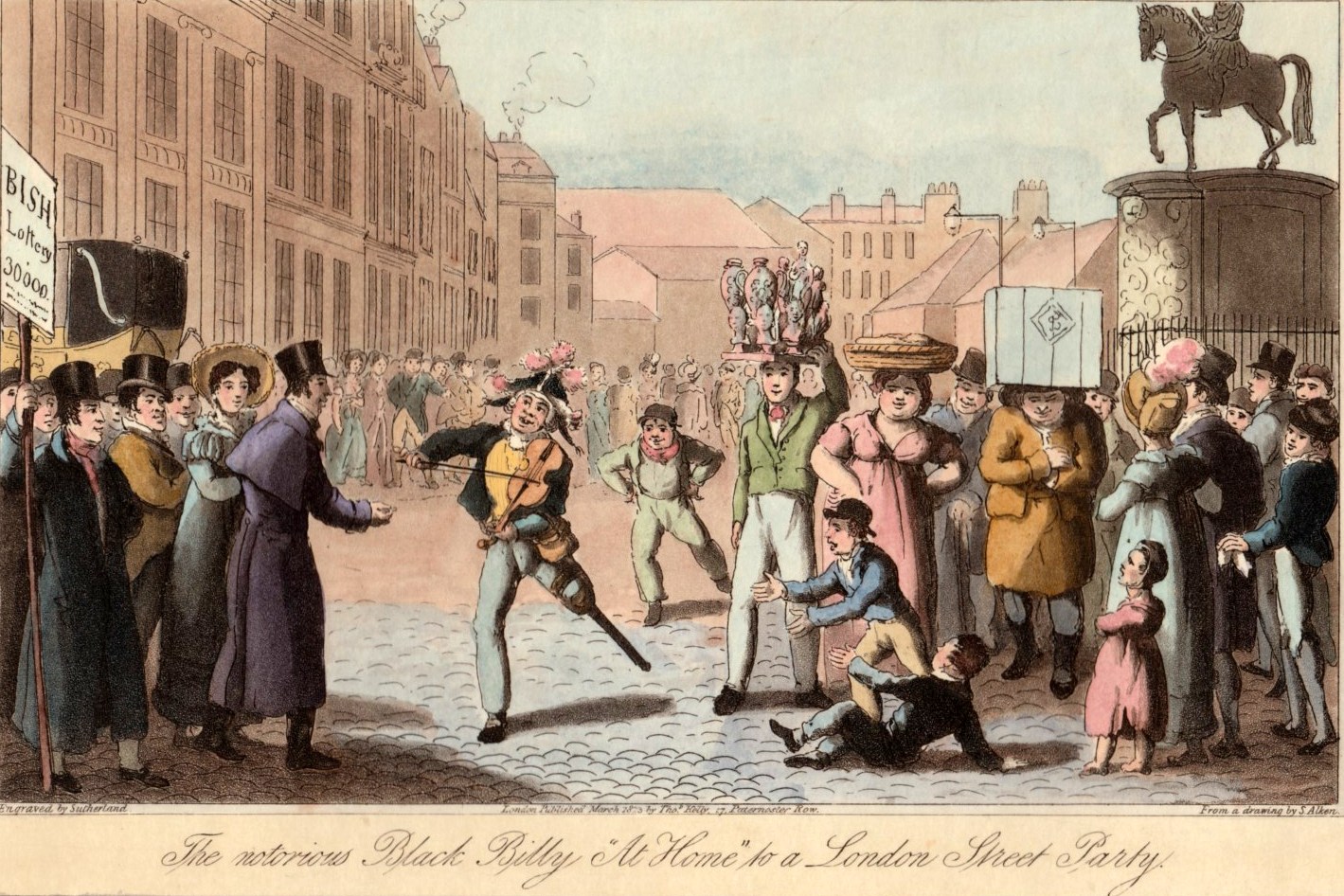

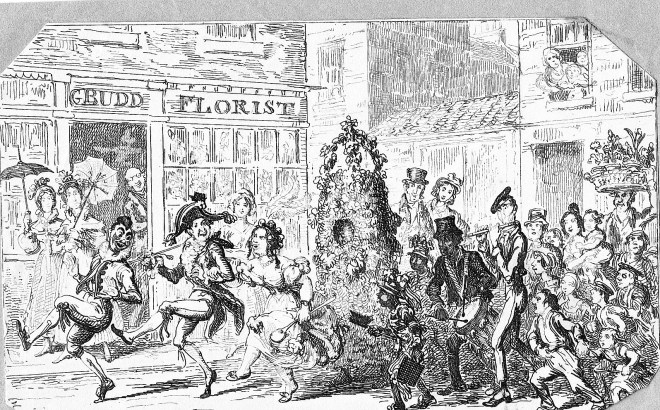

May Day appears to have particular significance for chimney sweeps. In Brand’s “Observations on Popular Antiquities…Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies and Superstitions.” (1813) he notes “The young chimney-sweepers, some of whom are fantastically dressed in girls’ clothes, with a great profusion of brick dust by way of paint, gilt paper etc, making a noise with their shovels and brushes, are now the most striking objects in the celebration of May Day in the streets of London.” The little lad holding his brush in the centre foreground of this print by Cruickshank certainly seems cheerful enough.

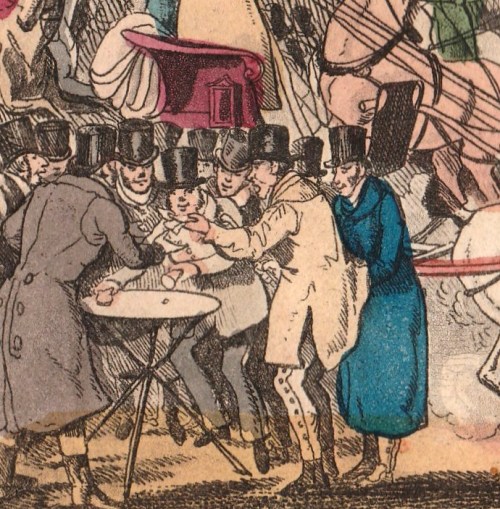

At Mrs Montague’s feast tables were set out in the gardens and “servants in livery [waited on] the sooty guests, with the greatest formality and attention.” Great crowds watched the gathering, “highly diverted with the many insolent airs assumed on the joyful occasion by the gentlemen of the brush, who, bedizened in their May-day paraphernalia, would rush through the crowd of spectators with all the arrogance of foreign princes.”

The reality of their everyday lives is more honestly seen in another Cruickshank print which shows how a boy trapped and suffocated in a chimney was removed. (The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album. Arranged by James Montgomery. Illustrations by George Cruickshank (1824)).

In the south-west corner was the residence of Monsieur Otto, negotiator for the French of the Peace of Amiens, signed 27 March 1802. He displayed illuminations in the square to mark the event and they can be seen in a print in the British Museum collection.

Ackermann’s also records that the residence of the Ottoman ambassador to the British court was on the west side of the square and, “Whilst the ambassador continued here, this square was the resort of all the beauty and fashion of this district of the metropolis.”

The square has suffered from bombing and redevelopment but number 20, Home House designed by Robert Adam, survives. In the print of the square above it is the tallest block.

Orchard Street leads southwards out of the square in the south-east corner. This is where Jane Austen’s aunt Mrs Hancock and her cousin Eliza were living in August 1788 when Jane dined with them during her first recorded visit to London.

Going east from the same corner was Edwards Street, now included in Wigmore Street, the location of Society caterer Parmentier.

From the north east corner Baker Street runs north. In the guide book The Picture of London, Baker Street was described as “perhaps the handsomest street in London.” It can no longer be said to be of much interest, except to record that it led to the Hindoostanee Coffee House in Baker Street, the site of the first Indian restaurant in London. It was opened in 1810 by Sake Dean Mohammed who became famous in Margate for his lavish bath house. The coffee house was less successful and closed within the year. You can read more about him here.

The area around Portman Square forms Walk Two in my Walking Jane Austen’s London.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

But the highwayman was a popular figure (at least, if you weren’t one of his victims). The crowd loved a villain, especially one who robbed those better off than themselves, carried out daring raids and escapes and, when almost inevitably brought to justice, “died game” on the gallows. Reality was less romantic – even the famous Dick Turpin, shown here on Black Bess, was a violent thug who tortured victims and inn keepers. The dashing Frenchman, Claude du Vall was hanged at Tyburn January 1670 despite (according to legend) gallantly sparing the possessions of any pretty lady who was prepared to dance with him. Presumably the plain ones just got robbed. The Victorians loved him and he was immortalized in a painting by Frith.

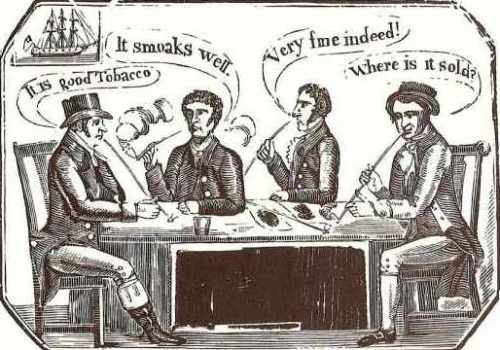

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.

The popularity and availability of cigarettes finally killed off the clay pipe but for hundreds of years tens of thousands were turned out. In an inn a customer could order a pipe along with his ale and lead tobacco boxes were provided on the tables for communal smoking. The lead kept the tobacco moist and they contained a weight-plate inside to press it down. They are scarce now – many got knocked off pub tables and the soft lead was damaged on stone floors – but I own a dozen or so. This example, complete with its internal plate and a wonderful lid covered in grape vines, shows crossed churchwarden pipes on its side.

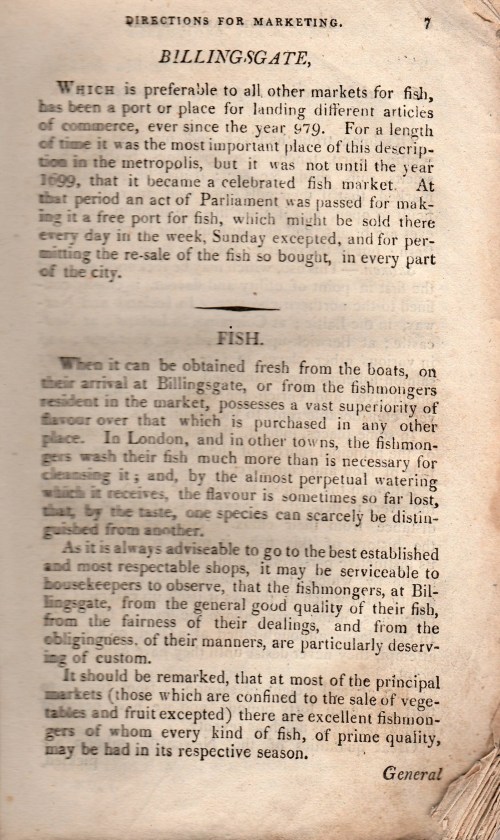

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.

Many of the fish were caught in the Thames and in 1828 a Parliamentary Committee took evidence that in 1798 there were 400 fishermen, each owning a boat and employing one boy, who made a good living between Deptford and London catching roach, plaice, smelts, flounders, shad, eels, dudgeon, dace and dabs. One witness stated that in 1810 3,000 Thames salmon were landed in the season. By the time of the Commission,eighteen years later, the fishery had been destroyed by the massive pollution of the river from water closets and the waste from gas works and factories that went straight into the river.