1 Sunday 26th February – Saturday 4th March 1815

Two hundred years ago today the King of Elba – Napoleon Bonaparte – was putting the final touches to his audacious plan to escape from his tiny island kingdom and take back his empire. He knew his position was increasingly insecure – at best he faced an impoverished exile, for he knew King Louis was unlikely to keep paying his pension. At worst he feared assassination or imprisonment. The print below is a detail of one published by Phillips in 1814 showing Napoleon on his way to Elba.

At the Congress in Vienna the great powers negotiated over the future of Europe while in London people argued abo ut the falling price of wheat, worried over the problem of unemployed ex-soldiers – many of them seriously disabled – begging on the streets and enjoyed some of the fruits of peace such as cheap bread for the poor, continental tourism for the rich.

ut the falling price of wheat, worried over the problem of unemployed ex-soldiers – many of them seriously disabled – begging on the streets and enjoyed some of the fruits of peace such as cheap bread for the poor, continental tourism for the rich.

I was intrigued to discover just what Londoners knew about the crisis on the continent as it unfolded and how they were spending their time when they did know that the “Corsican Monster” was on the loose again, so in addition to my usual blogs about life in Georgian London I will be posting a weekly account every Thursday of London life in the shadow of war and the countdown to the Battle of Waterloo.

On Elba that Sunday morning the weather was fine and calm. Rumours were rife on the island that Napoleon was escaping, although they did not appear to have reached the naval ships who were, rather casually, keeping an eye on him. Napoleon gave his morning levée dressed with great care in the coat of a grenadier officer in the Guards and wearing the Légion d’Honneur. He spent the day in last-minute preparations and paperwork and finally, after nightfall, accompanied his suite down to the harbour, to board the brig Inconstant along with the grenadiers of the Guard and his suite – about five hundred people in all. Other troops – Polish lancers, gunners and so forth, were loaded into the Saint Esprit, a merchant ship and the Caroline, a small flat-bottomed ship that could be run up on to a beach. In total there were about 1,100 men, four cannon, and forty horses. A cannon fired and, on a dangerously light breeze, Napoleon was carried slowly away from Elba.

Meanwhile, in London, divine service was held at Carlton House by the Reverend s Blomberg and Clerke and the newspapers were speculating that another row of properties were to be purchased by the Prince Regent in Brighton to allow for the expansion of the Pavilion. The likely cost was commented upon – unfavourably.

s Blomberg and Clerke and the newspapers were speculating that another row of properties were to be purchased by the Prince Regent in Brighton to allow for the expansion of the Pavilion. The likely cost was commented upon – unfavourably.

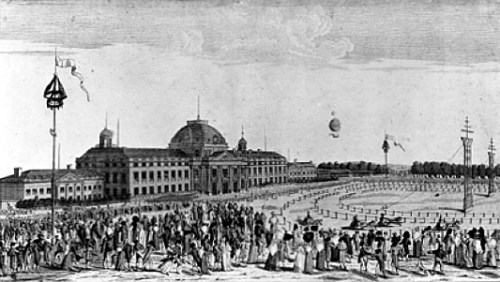

On Monday, while Napoleon’s little flotilla was creeping north-west on the very lightest of winds, missing British warships by the skin of his teeth and incredible good luck, Henry Aston Barker, proprietor of the Panorama, Leicester Square was advertising that “The beautiful VIEW OF MALTA will positively CLOSE on Saturday 11th March. The splendid Battle of Vittoria will also be closed in a few weeks. Open from 10 till dusk. Admission to each painting 1s.” Interest in the French wars was, perhaps, fading. In this print the entrance to the Panorama can just be seen to the side of Isaac Newton’s drapery business with “Rome, Malta” over the door.

Ironically most newspapers carried an advertisement informing readers that “PRINCE LUCIEN BONAPARTE’S MAGNIFICENT COLLECTION OF PICTURES is now open to the Public, and will be Sold by Private Contract, individually, at the New Gallery, no.60 Pall-mall. Admittance 1s. Descriptive catalogue 1s 6d.”

The local papers had, understandably, more parochial concerns. Readers could discover that a reward of £100 was offered for the discovery of the murder of Mary Hall, wife of Henry Hall, labourer at Dagnall in Buckinghamshire, with a free pardon to any accomplice making such discovery, or be amazed by the item in the Birmingham Daily Post announcing under the heading “Early Closing” that the “drapers of the town of Bromsgrove have resolved in future to close their establishments at ten instead of eleven o’clock on Saturday nights.” Such liberality to the employees! The London papers also reported that, “In consequence of the Chancellor of the Exchequer not having proposed any new tax on beer the principal brewers of Portsmouth and neighbourhood have met together and have decided to lower the price of beer this day to 5d per pot.”

Far more seriously, from Vienna, the Times reported, ”The discussions on the slave trade have been very warm at the Congress. Lord Castlereagh was extremely anxious to take with him its abolition, but he met with opponents worthy of him. It was in vain that he made a pompous display of philanthropy; it was thought to be visible that he was more occupied by the interest of his own country, than by the love of humanity.”

For those for whom the cost of beer was of little importance, Mr T W Lord advertised dancing lessons: “to give instruction in the most fashionable style and by his easy & superior methods they are soon perfectly qualified to appear in the first circles. The German Waltz may be attained in Six Lessons.” The print below is from La Belle Assemblee (1817) and shows a waltz class in action.

Meanwhile Napoleon’s ships continued unmolested, or even challenged, and at 1 p.m. on March 1st they passed Antibes and anchored at Golfe Juan. The first troops to land met no opposition and just after 4 p.m. Napoleon was rowed ashore to set foot once more on French soil. Antibes was too well defended to attack, so Napoleon went into Cannes, where he met neither opposition, nor much enthusiasm, and led his army north up the rough road that led to Grasse and the north.

By hard marching over very difficult terrain he reached Digne, 87 miles from the coast, on Saturday 4th March. He was greeted with enthusiasm – and the news of his landing finally reached Paris by telegraph. London and Vienna were quite unaware of what had occurred.

On 5th March I’ll blog about the next week, as London, in the grip of the Corn Law riots, continued in ignorance of the invasion, the King of France dithered and the news of Napoleon’s escape reached Vienna – and the Duke of Wellington.

Battlefield Brides – three Waterloo heroes and the women who went to war with them:

Sarah Mallory – A Lady For Lord Randall (May 2015)

Annie Burrows – A Mistress For Major Bartlett

Louise Allen – A Rose for Major Flint (July 2015)