It is cold outside as I write, which made me think about ice cream, one of my favourite treats.

It is easy to obtain now, but ice cream was a real luxury in the early 19thc. There was no way of making ice artificially and it had to be harvested and stored. This was was easy enough if you had a large estate with lakes and ponds that would freeze in winter and you employed staff to do the work. Slabs of ice were cut and packed in ice houses where they could be insulated with thick walls and straw to keep the ice right through the year. The building above is the ice house in the park of Holkham Hall in Norfolk. (© AJ Hilton)

In towns and cities loads of ice were brought in by wagon and would be stored in insulated pits. In 2018 MOLA (the Museum of London Archaeology) discovered a vast “ice well” when they were working on the site of the redevelopment of one of John Nash’s terrace close to Regent’s Park. The well had been constructed in the 1780s by Samuel Dash, connected to the brewing trade.

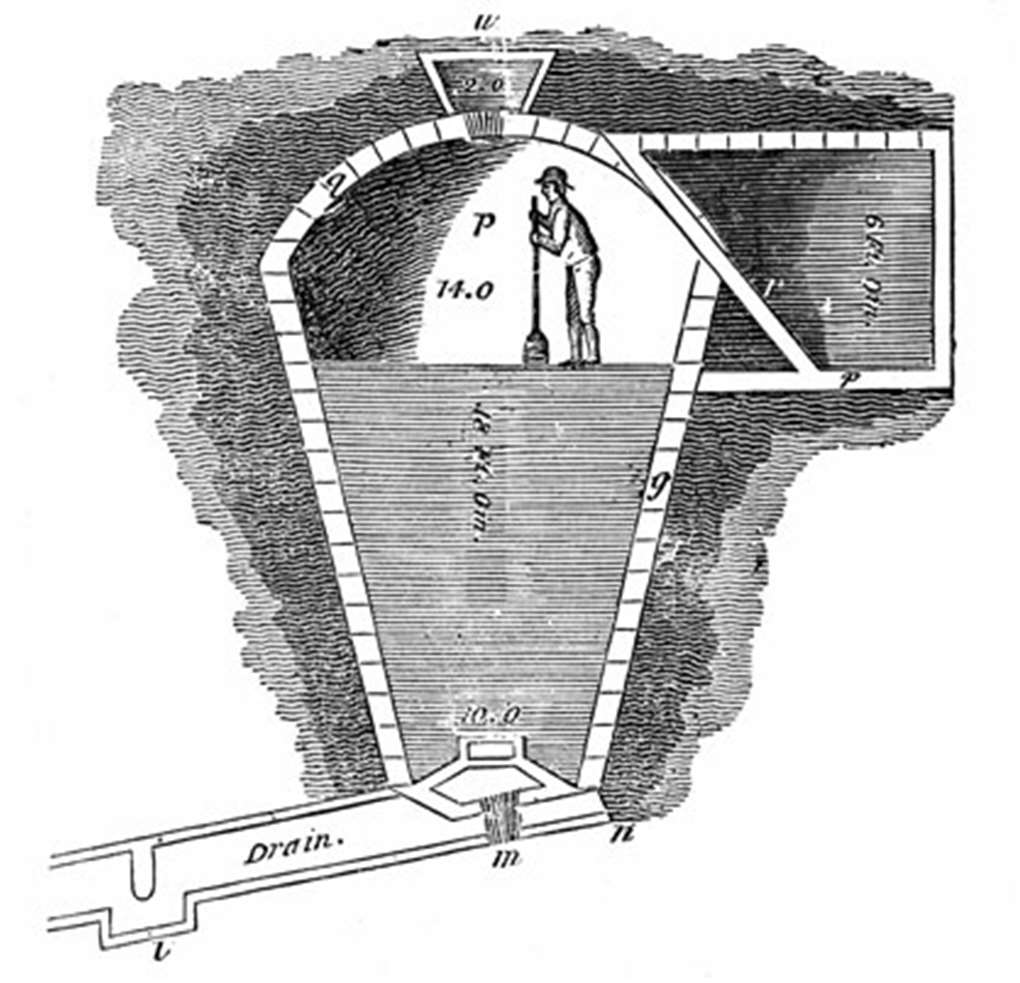

The structure is 7.5 metres wide and 9.5m deep, a red brick, egg-shaped chamber with an entrance passage, and vaulted ante-chamber. You can see an image of it on the MOLA website. The diagram below shows a similar pit, but unlike the Regent’s Park, example the “egg” is standing on its pointed end. The Regent’s Park design seems more logical to prevent melting – the greatest mass of the ice would remain deepest in the earth with as small an area as possible exposed at the top. However the other way up would make access to gather ice more convenient.

By the 1840s ice was being shipped in from Norway and from the Wenham Lake Ice Company in Massachusetts and was brought into the heart of London on the Regent’s Canal.

I own a copy of The Complete Confectioner or, the Whole Art of Confectionary Made Easy by Frederick Nutt (1815 and wrote about ice cream with a recipe from his book some time ago.

Looking at my copy of the 1829 edition A New System of Domestic Cookery…Adapted To The Use of Private Families by “A Lady” it is clear that she expected that the well-equipped cook would own an ice bucket and an “ice-pot”. Get a few pounds of ice, break it almost to powder, throw a large handful and a half of rock salt among it. You must prepare it in a part of the house where as little of the warm air comes as you can possibly contrive. The ice and salt being in a bucket, put your cream into an ice-pot, and cover it; immerse it in the ice, and draw that round the pot, so as to touch every possible part. She then gives instructions to stir it regularly – the method is exactly that used today in the absence of an ice cream maker.

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005).

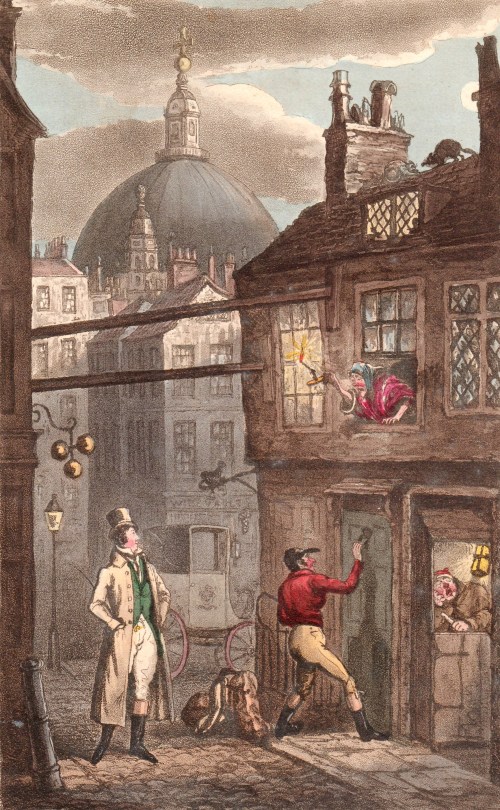

For a fascinating history of Europe’s love affair with curry, try Lizzie Collingham’s Curry; a biography (2005). You are slumming it in Regency London – perhaps you’re in cheap lodgings avoiding your creditors, or dodging a furious father armed with a shotgun or your gambling habit has got the better of you and you are seriously out of pocket. You have found your cheap lodgings – a miserable, unheated room that you share with bedbugs, fleas, mice and the other inhabitants of your straw pallet – now you need to find something to eat. [The print above is of Logic’s lodgings in one of the Tom & Jerry tales by Pierce Egan. Note the dome of St Paul’s behind and the pawnbroker’s shop with its three gold balls on the left.]

You are slumming it in Regency London – perhaps you’re in cheap lodgings avoiding your creditors, or dodging a furious father armed with a shotgun or your gambling habit has got the better of you and you are seriously out of pocket. You have found your cheap lodgings – a miserable, unheated room that you share with bedbugs, fleas, mice and the other inhabitants of your straw pallet – now you need to find something to eat. [The print above is of Logic’s lodgings in one of the Tom & Jerry tales by Pierce Egan. Note the dome of St Paul’s behind and the pawnbroker’s shop with its three gold balls on the left.]

Francis Grose toured the back-slums and the rookeries of London in the 1780s collecting cant and slang terms for his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, assisted (or possibly supported) by his servant Batch. Judging by his portrait Grose had sampled plenty of naked boys, aldermen and Bloody Jemmys himself. He inspired a number of imitators (and downright plagiarists) but all these late Georgian slang dictionaries are arranged in alphabetical order of the terms defined.

Francis Grose toured the back-slums and the rookeries of London in the 1780s collecting cant and slang terms for his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, assisted (or possibly supported) by his servant Batch. Judging by his portrait Grose had sampled plenty of naked boys, aldermen and Bloody Jemmys himself. He inspired a number of imitators (and downright plagiarists) but all these late Georgian slang dictionaries are arranged in alphabetical order of the terms defined.