The romance and drama of an elopement is a popular theme in the historical love story, but it must have been an uncomfortable and expensive procedure, even without the risk of the rope ladder giving way and tumbling the young lady to the ground, or the furious father giving chase with his shotgun or horsewhip to chastise the bridegroom to within an inch of his life.

The post chaise was the fastest and safest way of evading Papa, although the popular name for these vehicles – yellow bounders – hints that expressions of passion must have been difficult as it swayed and lurched along the ill-made roads. How many nervous brides succumbed to travel sickness and second thoughts by the time the first inn was reached?

They also had a reputation for causing accidents because of the furious pace of escape, as a delightful print I picked up in Paris shows. A chaise and four, with the two postilions urging on the horses, leaves mayhem in its wake. A horse falls, its rider spills into the road and a pig bolts in terror while the lovers are lost to everything in their own private world inside the carriage.

The Great North Road by Charles G Harper (1901) casts a cynical eyes at the post chaise and its passengers –

“Everyone is familiar with the appearance of the old post-chaise, which according to the painters and the print-sellers, appears to have been principally used for the purpose of spiriting lovelorn couples with the-speed of the wind away from all restrictions of home and the Court of Chancery. A post-chaise was (so it seems nowadays) a rather cumbrous affair, four-wheeled, high, and insecurely hung, with a glass front and a seat to hold three, facing the horses. The original designers evidently had no prophetic visions as to this especial popularity of post-chaises with errant lovers, nor did they ponder the proverb, ‘Two’s company, three’s none’, else they would have restricted their accommodation to two, or have enlarged it to four.”

The gentleman planning an elopement would do well to visit his banker first – eloping in any style was an expensive business. There were the bribes of course – the lady’s maid, footmen who must turn a blind eye, the gardener whose ladder might be borrowed. The postilions, who would know at once that something illicit was afoot, would need their palms greasing liberally as would the landladies of the inns along the way if the happy, if queasy, couple wanted a good room for their first night of bliss.

The image above is from a book called Takings: or the Life of a Collegian. It is a satirical romp through the life of a young man by R.Dagley (1821). The picture is captioned ‘Taking Amiss’. Here the ‘hero’ Tom is eloping with his love – note the sign on the wall ‘To the Boarding School’ – the young lady is clearly below age.

At length the wished-for moment was at hand.

(Why should Time creep so slowly when we call?)

The cautious signal by the lovers plann’d,

Was heard and answere’d by the garden-wall

And now her drapery the nymph displays,

Now they [Tom has a friend along to support him] assist, and seat her in the chaise.

Not everything goes according to Tom’s plans, however: “One lodging, he conceived, for both would do, But Charlotte resolutely called for two”. Frustrated, Tom settles down to woo her, but has not succeeded by the time her furious relatives locate them and he finds himself facing a duel.

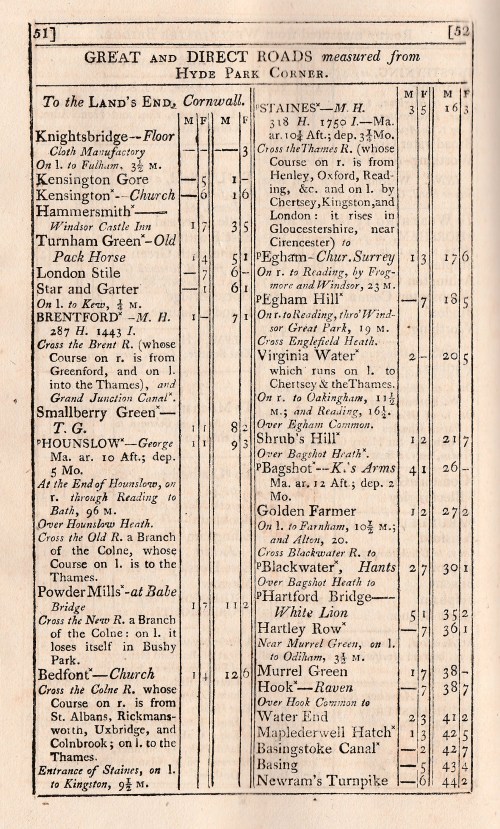

Another significant cost was the hire of the post chaise itself. A prudent lover would hire four horses, to achieve twelve miles an hour, and the chaise cost one-and-threepence a mile. On top of that there were toll gates to pay every few miles and food and accommodation. The canny eloper armed himself with Cary’s New Itinerary or an Accurate Delineation of the Great Roads (as does the writer trying to work out her hero and heroine’s route today!) This at least ensured that the post boys were not adding on a profitable mile here and there.

London to Gretna via Manchester, according to Cary, is 320 miles. That is £20 for the chaise and horses alone, at a time when a housemaid would be glad to earn £16 a year, all found.

Does an elopement still strike you as romantic? Would the thrill of the escape and the delight of being alone with the loved one at last outweigh the discomfort and expense? It is a while since I wrote an elopement into a book – I wonder, should I be thinking of another one?

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in Driving Through Georgian Britain: the great coaching routes for the modern traveller. Available in paperback and ebook it allows the modern traveller to drive the Great North Road, the Bath Road, the Brighton Road and the Dover Road finding what remains and discovering stories of elopement, murder, good meals and bare knuckle fights along the way.

If you are intrigued by the experience of travelling in Georgian Britain you can retrace some of the iconic routes in Driving Through Georgian Britain: the great coaching routes for the modern traveller. Available in paperback and ebook it allows the modern traveller to drive the Great North Road, the Bath Road, the Brighton Road and the Dover Road finding what remains and discovering stories of elopement, murder, good meals and bare knuckle fights along the way.

The first footman, two more footmen, two maids (more of those can be hired locally along with assorted kitchen skivvies) and Gaston the chef, left three days before to set up the house on the Esplanade and hire extra staff and furnishings required. That involved two lumbering old coaches plus a baggage coach.

The first footman, two more footmen, two maids (more of those can be hired locally along with assorted kitchen skivvies) and Gaston the chef, left three days before to set up the house on the Esplanade and hire extra staff and furnishings required. That involved two lumbering old coaches plus a baggage coach.

stagecoaches appeared in the mid-17th century – and wise passengers made their will before setting out as well as allowing considerable time – the 182 miles from London to Chester took six days in 1657 (if the weather was kind). But at least in those days speed was not going to kill you and the coach would stop overnight so you had a chance of a meal at your leisure and a night’s sleep. (Prudent travellers would bring their own bed linen). If you were very hard up and could not afford the £1 15s for the London-Chester route you could perch on the roof (no seats or handrail) or ride in the basket with the luggage. To be ‘in the basket’ became slang for being hard-up. Passengers riding this way can be seen in this print of the quite fabulous sign (below) for the White Hart, Scole, Norfolk. The sign really was this ornate and was unfortunately demolished as a traffic hazard in the 19th century. The inn is still operating.

stagecoaches appeared in the mid-17th century – and wise passengers made their will before setting out as well as allowing considerable time – the 182 miles from London to Chester took six days in 1657 (if the weather was kind). But at least in those days speed was not going to kill you and the coach would stop overnight so you had a chance of a meal at your leisure and a night’s sleep. (Prudent travellers would bring their own bed linen). If you were very hard up and could not afford the £1 15s for the London-Chester route you could perch on the roof (no seats or handrail) or ride in the basket with the luggage. To be ‘in the basket’ became slang for being hard-up. Passengers riding this way can be seen in this print of the quite fabulous sign (below) for the White Hart, Scole, Norfolk. The sign really was this ornate and was unfortunately demolished as a traffic hazard in the 19th century. The inn is still operating.