In Sense and Sensibility one of John Dashwood’s feeble excuses for not calling promptly on his half-sisters was that he had to take his young son Harry to see the wild beasts at Exeter Change on the Strand.

In Sense and Sensibility one of John Dashwood’s feeble excuses for not calling promptly on his half-sisters was that he had to take his young son Harry to see the wild beasts at Exeter Change on the Strand.

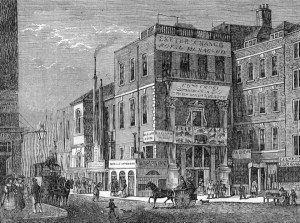

I was prompted to find out more when I bought a print from Ackermann’s Repository which shows the interior of “Polito’s Royal Menagerie” in 1812 and then found a copper token issued by one of the earlier owners, Mr Pidcock. “The collection of divers beasts and birds [was] only exceeded in rarity by those of the Royal Menagerie in the Tower,” according to The Picture of London for 1807, but what neither the guide book nor the Ackermann’s article appear to find worthy of comment was that this little zoo was on the first floor of a building otherwise occupied by shops and offices. The collection included at various times adult elephants, two rhinoceroses, a pair of kangaroos, a “gigantic male ostrich”, a Bengal tig er and a pair of lions. How any of these were coaxed or carried up a flight of stairs is not explained.

er and a pair of lions. How any of these were coaxed or carried up a flight of stairs is not explained.

Exeter Change was built in around 1676 as a not very successful collection of small shops specialising in millinery, drapery and hosiery, but by the late 18th century many were let as offices. An animal dealer, Thomas Clark, began a menagerie on the first floor in 1770, advertising that the animals could be viewed “in complete safety.” In 1793 Gilbert Pidock, who had been using it as a winter headquarters for his travelling show, bought the menagerie and on his death in 1810 it was acquired by an Italian, Stephen Polito, and renamed The Royal Menagerie.

Edward Cross worked for Polito and his daughter married Polito’s brother. When Polito died in 1814 Cross took over the menagerie. He tried on two occasions to sell the collection to the Zoological Society of London and moved it to the Royal Mews on the site of The National Gallery when Exeter Change was demolished in 1829. He eventually managed to sell some animals to the new London Zoo and moved the rest to the Surrey Zoological Gardens, which he created.

The Morning Chronicle for 17 May 1808 reported that, “The grandest spectacle in the universe is now prepared at Pidco ck’s Royal Menagerie, Exeter Change, Strand, where a most uncommon collection of foreign beasts and birds, many of them never before seen alive in Europe, are ready to entertain the wondering spectators. This affords an excellent opportunity for Ladies and Gentlemen to treat themselves with a view of some of the most beautiful and rare animals in creation. Amongst innumerable others are five noble African lions, tigers, nylghaws, beavers, kangaroos, grand cassowary, emus, ostriches etc. Indeed such a numerous assemblage of living birds and beasts may not be found for a century. This wonderful collection is divided into three apartments, at one shilling each person, or the three rooms for two shillings and sixpence each person.”

ck’s Royal Menagerie, Exeter Change, Strand, where a most uncommon collection of foreign beasts and birds, many of them never before seen alive in Europe, are ready to entertain the wondering spectators. This affords an excellent opportunity for Ladies and Gentlemen to treat themselves with a view of some of the most beautiful and rare animals in creation. Amongst innumerable others are five noble African lions, tigers, nylghaws, beavers, kangaroos, grand cassowary, emus, ostriches etc. Indeed such a numerous assemblage of living birds and beasts may not be found for a century. This wonderful collection is divided into three apartments, at one shilling each person, or the three rooms for two shillings and sixpence each person.”

Of course the conditions were utterly unsuited to keeping wild animals and complaints were made even in the early 19th century. In 1796 Pidcock had three elephants in one room. The most horrifying example of the cruelty was the fate of Chunee the elephant who weighted 5 tonnes and who became so irritable – understandably in view of a rotten and untreated tusk – that in 1826 it was decided he must be destroyed. When the first attempt to kill him by shooting failed, soldiers were brought from Somerset House further along the Strand. They also failed to destroy the poor creature, now maddened by pain and a cannon was ordered. Thankfully the keeper managed to kill Chunee before it arrived. The carcase was dissected by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Numerous copper tokens were issued for the menagerie. These were produced for many businesses in the late 18th century to supplement the poor supply of small coinage. The one I own shows an elephant with the words “Pidcock’s Exhibition” on one side and a bird and “Exeter Change, Strand London” on the other. Other designs showed lions, beavers and a rhino.

Celebrity visitors included Lord Byron, who was amused by Chunee taking his money and then courteously returning it. He also saw a hippopotamus there which, he said, reminded him of Lord Liverpool.

As the Ackermann’s print shows, this was very much a family entertainment. In my next post I’ll visit Bullock’s Museum where the public could view a wide range of exotic species, but, probably fortunately for the animals concerned, all stuffed.

As the Ackermann’s print shows, this was very much a family entertainment. In my next post I’ll visit Bullock’s Museum where the public could view a wide range of exotic species, but, probably fortunately for the animals concerned, all stuffed.

stagecoaches appeared in the mid-17th century – and wise passengers made their will before setting out as well as allowing considerable time – the 182 miles from London to Chester took six days in 1657 (if the weather was kind). But at least in those days speed was not going to kill you and the coach would stop overnight so you had a chance of a meal at your leisure and a night’s sleep. (Prudent travellers would bring their own bed linen). If you were very hard up and could not afford the £1 15s for the London-Chester route you could perch on the roof (no seats or handrail) or ride in the basket with the luggage. To be ‘in the basket’ became slang for being hard-up. Passengers riding this way can be seen in this print of the quite fabulous sign (below) for the White Hart, Scole, Norfolk. The sign really was this ornate and was unfortunately demolished as a traffic hazard in the 19th century. The inn is still operating.

stagecoaches appeared in the mid-17th century – and wise passengers made their will before setting out as well as allowing considerable time – the 182 miles from London to Chester took six days in 1657 (if the weather was kind). But at least in those days speed was not going to kill you and the coach would stop overnight so you had a chance of a meal at your leisure and a night’s sleep. (Prudent travellers would bring their own bed linen). If you were very hard up and could not afford the £1 15s for the London-Chester route you could perch on the roof (no seats or handrail) or ride in the basket with the luggage. To be ‘in the basket’ became slang for being hard-up. Passengers riding this way can be seen in this print of the quite fabulous sign (below) for the White Hart, Scole, Norfolk. The sign really was this ornate and was unfortunately demolished as a traffic hazard in the 19th century. The inn is still operating.

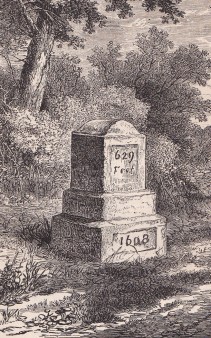

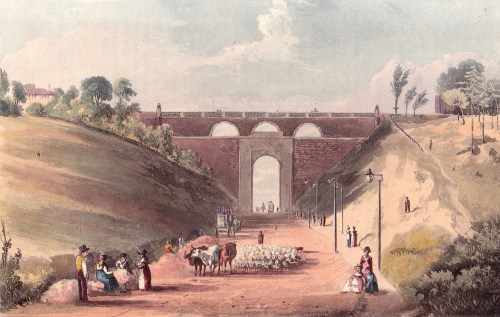

on. Ahead lies Archway Road running through a deep cutting and spanned after half a kilometre by the bridge carrying Hornsea Lane over the top. If you want to visit Highgate Village itself you need to take the fork off the one-way system just before Archway Road, to drive up Highgate Hill, past the modern Whittington Stone pub and the Whittington Stone itself sitting beside the pavement.

on. Ahead lies Archway Road running through a deep cutting and spanned after half a kilometre by the bridge carrying Hornsea Lane over the top. If you want to visit Highgate Village itself you need to take the fork off the one-way system just before Archway Road, to drive up Highgate Hill, past the modern Whittington Stone pub and the Whittington Stone itself sitting beside the pavement.

shows Holloway Road coming in from the right and the tollgate before Archway Hill.

shows Holloway Road coming in from the right and the tollgate before Archway Hill.