I went to Antarctica in the Spring expecting to have a complete holiday from the Regency. When we sailed past Coronation Island in the South Orkney Group I assumed it was named for Queen Victoria’s crowning, or even a later monarch. But no, this island (one of three so named worldwide) commemorates George IV and was named in December 1821 by two very early Antarctic explorers, the sealers Captain Nathaniel Palmer (American) and Captain George Powell (British). Either news was reaching south very fast or Powell, knowing when he had left British shores that George had become king in 1820, named the island retrospectively. He certainly claimed the South Orkneys in the name of the King – quite how much discussion about that went on with his American colleague is not recorded! If Powell was hoping for royal favour he unfortunately did not live to receive it, dying in Tonga in 1824.

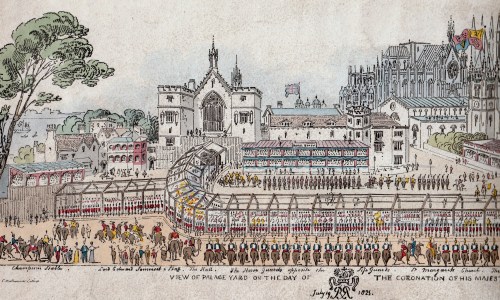

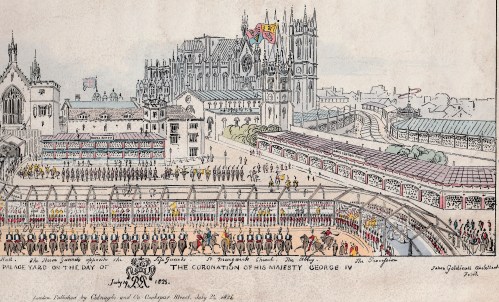

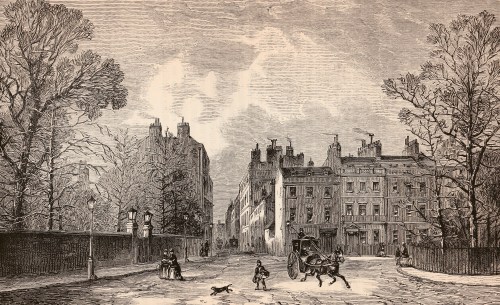

Back in London on 19 July 1821 George IV was crowned in one of the most magnificent, and completely over the top, coronations in British history. The entire day was too packed with incident for one blog post – not least the dreadful spectacle of the distraught Queen trying to gain admittance to the Abbey – so I’ll just concentrate on the procession itself. The print I am working from was published on July 24th, just three days after the coronation, and the artist is giving the view from approximately what is now the bottom of Whitehall looking out over the modern Parliament Square in the right foreground and New Palace Yard on the left, now enclosed by railings. The Thames can be glimpsed to the left and Westminster Bridge is beyond the large tree.

I have had to scan the print in halves because of its size. It shows clearly the covered processional way (coverings not shown in order to reveal the participants) weaving its way from the front of Westminster Hall on the left, snaking round the gardens in front of St Margaret’s Church (in front of the Abbey with the Royal Standard flying from its tower) and disappearing from sight before its entry at the West door of the Abbey.

The covered walk was twenty five feet wide (almost eight metres), covered in blue carpet and raised three feet (a metre) above the ground so spectators had the best possible view. The route was lined with stands and galleries with ticketed seats selling from two to twenty guineas each. (That might have helped pay for almost half a mile of blue carpet!)

The procession started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

started half an hour late at half past ten in the morning and was headed by the King’s Herb-Woman and six attendant maids scattering sweet-smelling herbs and petals. Behind them came the chief officers of state, all in specially designed outfits and carrying the crown, the orb and the sceptre, preceded by the Sword of State and accompanied by three bishops carrying the paten, chalice and Bible to be used in the ceremony. The peers in order of precedent, splendid in the robes, followed next and those Privy Councillors who were commoners had their own uniform of Elizabethan costume in white and blue satin.

The King wearing a black curled wig and a black Spanish hat with white ostrich feather plumes had a twenty seven foot long train of crimson velvet spangled with gold stars and walked to the Abbey under a canopy of cloth-of-gold carried by the Barons of the Cinque Ports (also in special outfits). Music was provided by the Household Band.

After the ceremony, at four o’clock the King, now very weary, walked back to Westminster Hall and the great banquet served to three hundred and twelve male guests. Ladies and peeresses, who were not served any refreshments, had to watch their menfolk gorging themselves from the massed galleries that had been built inside the Hall. Amongst the food were 160 tureens of soup. 80 dishes of braised beef, 160 roast joints, 480 sauce boats, 1,190 side dishes and 400 jellies and creams.

The climax of the banquet was the arrival of the King’s Champion, in full armour, mounted on a white charger. The Champion threw down his gauntlet three times, but no-one stepped forward to challenge the King who toasted his Champion from a gold cup. Possibly the medieval glamour of the moment might have been diminished if people had realised that the Champion, from a family who long held the hereditary position, was actually the twenty year old son of a Lincolnshire rector and his charger had borrowed from Astley’s Amphitheatre.

The Champion’s stable is visible on the extreme left of the print.

‘There is a bonnet here I thought might suit you, Miss Gatwick,’ he confesses, remembering to address her properly and not by her given name as he always thinks of her. ‘You see? That one on the stand.’

‘There is a bonnet here I thought might suit you, Miss Gatwick,’ he confesses, remembering to address her properly and not by her given name as he always thinks of her. ‘You see? That one on the stand.’

Emily gives him a beaming smile, much restored by thoughts of shopping, as they reach the circulating library. Porrett, having established that the monthly subscription is eight shillings, deals with the business side, taking out a subscription for both senior ladies. He also subscribes for himself, for he has a secret penchant for poetry and intends to take a slim volume off to the garden where he can brood on his heartache in peace. (Above, the artist of a Regency ‘bat print’ bowl has caught Porrett immersed in his poetry next to a beehive.)

Emily gives him a beaming smile, much restored by thoughts of shopping, as they reach the circulating library. Porrett, having established that the monthly subscription is eight shillings, deals with the business side, taking out a subscription for both senior ladies. He also subscribes for himself, for he has a secret penchant for poetry and intends to take a slim volume off to the garden where he can brood on his heartache in peace. (Above, the artist of a Regency ‘bat print’ bowl has caught Porrett immersed in his poetry next to a beehive.)

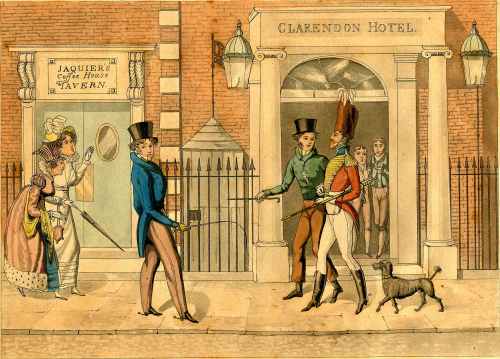

Finally, and most regally, there is The Cut Visible, the cut so blunt and obvious that no-one could mistake it. The Prince Regent’s version of this is known as Rumping. If he wishes to indicate that some former acquaintance is now persona non grata then Prinny simply turns his back on them at the last moment as they approach him. The unfortunate cuttee is then presented with a fine view of the expansive royal backside. (A fine view of the Royal Rump can be seen in this detail from a Cruickshank cartoon of 1819)

Finally, and most regally, there is The Cut Visible, the cut so blunt and obvious that no-one could mistake it. The Prince Regent’s version of this is known as Rumping. If he wishes to indicate that some former acquaintance is now persona non grata then Prinny simply turns his back on them at the last moment as they approach him. The unfortunate cuttee is then presented with a fine view of the expansive royal backside. (A fine view of the Royal Rump can be seen in this detail from a Cruickshank cartoon of 1819)

An invention of 1816, and applied to persons whose extravagant dress called forth the sneers of the vulgar; they were mostly young men who had this designation, and they were charged with wearing stays – a mistake easily fallen into, their wide web-belts having that appearance. Men of fashion became dandy soon after; having imported a good deal of French manner in their gait, lispings, wrinkled foreheads, killing king’s English, wearing immense pleated pantaloons, the coat cut away, small waistcoat, with cravat and chitterlings* immense: Hat small; hair frizzled and protruding. If one fell down he could not rise without assistance. Yet they assumed to be a little au militaire, and some wore mustachios. Lord Petersham was at the head of this sect of mannerists.

An invention of 1816, and applied to persons whose extravagant dress called forth the sneers of the vulgar; they were mostly young men who had this designation, and they were charged with wearing stays – a mistake easily fallen into, their wide web-belts having that appearance. Men of fashion became dandy soon after; having imported a good deal of French manner in their gait, lispings, wrinkled foreheads, killing king’s English, wearing immense pleated pantaloons, the coat cut away, small waistcoat, with cravat and chitterlings* immense: Hat small; hair frizzled and protruding. If one fell down he could not rise without assistance. Yet they assumed to be a little au militaire, and some wore mustachios. Lord Petersham was at the head of this sect of mannerists. Kid, Kiddy and Kidling implies youth; but an old evergreen chap may be dressed kiddily, i.e. knowingly, with his hat on one side, shirt-collar up on high, coat cut away in the skirts, or outside breast-pockets, a yellow, bird’s-eye-blue , or Belcher fogle*, circling his squeeze**, and a chitterling shirt*** of great magnitude protruding on the sight, and wagging as its wearer walks. These compounded compose the kiddy; and if father and son come it in the same style, the latter is a kidling.

Kid, Kiddy and Kidling implies youth; but an old evergreen chap may be dressed kiddily, i.e. knowingly, with his hat on one side, shirt-collar up on high, coat cut away in the skirts, or outside breast-pockets, a yellow, bird’s-eye-blue , or Belcher fogle*, circling his squeeze**, and a chitterling shirt*** of great magnitude protruding on the sight, and wagging as its wearer walks. These compounded compose the kiddy; and if father and son come it in the same style, the latter is a kidling.

and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of

and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of