Today if you want to travel from the middle of London to visit the smart shops of Kensington and Chelsea, or the museums of South Kensington, or go to a concert at the Albert Hall, you will travel along Knightsbridge, the road that stretches for a mile from Hyde Park Corner to the east to the Royal Albert Hall in the west (becoming, these days, Kensington Road and the beginnings of Kensington Gore in the process). Are you in London? Of course you are.

When Jane Austen was staying with her brother Henry in his homes in Sloane Street and Hans Place, she was just as clear that Knightsbridge (or Knights Bridge, as it was known almost until the 19th century), was not London. ‘If the Weather permits, Eliza & I walk into London this morng.’ she wrote in April 1809 from 64, Sloane Street.

(Above: Detail of Roque’s map of London 1741 showing Knight’s Bridge and the beginning of Kensington)

Although the tentacles of development were reaching out from the new Sloane Street, down the Brompton Road and along towards Kensington, London still began at the Hyde Park Turnpike, situated until 1825 just about where Grosvenor Place meets Knightsbridge today. Apsley House, which became the home of the Duke of Wellington, was the first dwelling you came to entering through the gates – Number One, London, in fact.

Knights Bridge was never a parish or a manor, only a locality, known from Saxon times as Kyngesburig, or Knightsbrigg. There are many legends about the origins of the name, but none appear to have any basis in fact. The bridge in question crossed the Westbourne River, one of London’s “lost rivers”, as it left Hyde Park, where it had been turned into the Serpentine. The Westbourne ran on south along a meandering course which marks the boundary of Chelsea and St George’s parishes to meet the Thames in the grounds of Chelsea Hospital. It was finally covered over in 1856/7 and became the unromantically-named Ranelagh Sewer and its outfall can still be seen at low tide. The Albert Gate of Hyde Park marks the point where it went under the road and William Street follows its line southwards.

If you had ventured this far in the time of the Tudors you would have encountered an appalling road, the “Waye to Reading”, mired so deep in mud that it contributed to the defeat of Sir Thomas Wyatt’s rebel army. They marched against Queen Mary, but arrived so exhausted by the state of the ‘road’ that they were easy prey for the royal troops. Things did not greatly improve for hundreds of years and even as late as 1842 reports were made of pavements ankle-deep in mud.

Worse than the mud were the highwaymen and footpads who infested this road. The last highway robbery on Knightsbridge was as late as 1799, after which a light horse patrol was sent out from the barracks to patrol the road and it was one of the earliest to have street lighting. Mr Davis in his “History of Knightsbridge” (1854) records that even after the armed patrols were instituted, “pedestrians walked to and from Kensington in bands sufficient to ensure mutual protection, starting their journey only at known intervals, of which a bell gave due warning.”

If we are feeling brave we can set out along this perilous mile, guided by the charming little map from Cecil Aldin’s The Romance of the Road (1928). East is at the top and we begin with the Hyde Park Corner tollgate and just before it, at the junction with Grosvenor Place, is St George’s Hospital. That is still there, but is now the Lanesborough Hotel. Behind it was Tattersall’s sale ring until it moved in 1865.

Going east we would have passed the White Hart Inn on the north side and a barracks for foot soldiers (demolished 1836) on the south. The narrow entrance to Old Barrack Yard still marks the spot. We cross the Westbourne as we pass William Street and can see today the unlovely round tower of the Sheraton Hotel. Once this was the site of a house owned by a Mr Lowndes and behind it, where Lowndes Square is now, was a rural pleasure garden, Spring Garden (not to be confused with the one of the same name next to what is now Trafalgar Square) at the sign of the “World’s End”. It is referred to in Pepys’s diaries several times, including in the final entry, May 31st 1669: “To the Park, Mary Botelier and a Dutch gentleman, a friend of hers being with us. Thence to the ‘World’s End’ a drinking house by the Park, and there merry, and so home late.”

(Below: Spring Gardens from a Victorian engraving of an earlier drawing.)

More or less opposite was Trinity Chapel which was probably medieval in origin and functioned as a hospital, or lazar house, for the poor. Traditionally it was said to have taken in plague victims in 1665 and the dead were buried opposite under Knightsbridge Green at the present junction of Knightsbridge, Sloane Street and Brompton Road. Eventually the chapel fell into total disrepair and was rebuilt. Its present incarnation is further along the road in Kensington.

For a long time before the passing of Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act in 1753 it was the location for irregular, clandestine or runaway marriages and the registers for the chapel contain entries with notes such as “secrecy for life” or “secret for fourteen years” added to them. Possibly the most famous person married there was Sir Robert Walpole who wed a daughter of the Lord Mayor of London. (The chapel is shown below in a view of part of the north side of Knightsbridge in 1820)

Now we reach the Albert Gate into Hyde Park, the point where the Westbourne still runs under our feet. On the park side of the bridge was the Fox and Bull Inn (shown as the Fox on Aldin’s map), patronised by artists such as George Morland and Sir Joshua Reynolds, who painted its sign. Less pleasantly it was a receiving house for the Humane Society, founded to assist drowning persons, or deal with their bodies. It was to this inn that the body of Harriet Shelley, the poet’s first wife, was brought after she drowned herself in the Serpentine in 1816. Immediately after the Fox and Bull was the Cannon Brewery, so called from the cannon mounted on its roof. That was surrounded by “low and filthy courts with open cellars” – a far cry from the elegant Kuwaiti and French Embassy buildings which occupy the site now.

Almost opposite is the junction with Sloane Street, developed after 1780 along the old track from the King’s Road in Chelsea. Another old road, the Brompton Road, comes in at an angle at the same point and led to the village of Brompton and on to Fulham. At this junction was Knightsbridge Green with a watch house for the constable, a pound for straying livestock, and possibly the site of Trinity Chapel’s plague pit. This was the point where the granite sets that made up the road surface ceased and the mud really began. It is also close to this point that Tattersall’s moved in 1865.

Just past the brewery were the barracks for the Horse Guards, giving them direct access into Hyde Park, just as they have today. Originally built in 1794/5 the barracks were rebuilt in 1878/9 and then again in the 20th century, slightly further west on Knightsbridge. From here on there were virtually no buildings on the north side, only the brick wall of Hyde Park. The road now becomes Kensington Road.

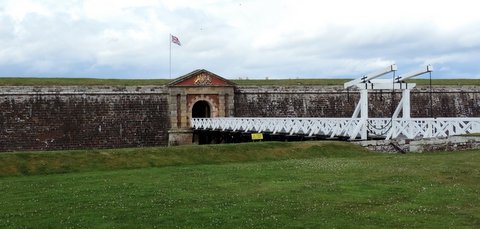

On the south side of Knightsbridge, following the Brompton Road turning, were the Rose and Crown (the oldest of Knightsbridge’s inns, shown below) and the Old King’s Head and then the floor-cloth manufactory of Messrs. Smith and Barber. It had been established in 1754 and lasted well into the Victorian era.

Then came three mansions that were, when they were built, true “country houses”. The first was Rutland House, the next Kent House, home for a while of the Duke of Kent, Queen Victoria’s father, and then Kingston House. Kingston House was built in 1769 for the scandalous Elizabeth Chudleigh whose story is so amazing that I will save it for another post. She died in 1796 and it later became the home of the Marquis of Wellesley who died there in 1842. He was the elder brother of the Duke of Wellington.

An area of nursery gardens followed on the south side of the road, part of the great expanse of fruit and vegetable-producing land that surrounded London. Somewhere along this stretch we enter what is now known as Kensington Gore – nothing to do with blood, but named after Gore House which stood on the site of the Royal Albert Hall. It was built in the 1750s, decorated by Robert Adam and was the home in the 1780s of Admiral Lord Rodney. It was acquired in 1808 by William Wilberforce, the great campaigner for the abolition of the slave trade, who lived there until 1821.

Opposite Gore House, a most insalubrious neighbour for a fine mansion, was the Halfway House Inn (shown above). This was where the spies for the highwaymen of Hounslow Heath would congregate to see who was travelling and pass the word on to alert the highwaymen about fine carriages or vulnerable riders. Just beyond it on the park side was the first milestone from the Hyde Park turnpike, the point where we can leave the dangers of Knightsbridge behind us and enter the village of Kensington with a sigh of relief for our arrival safe from the mud and the footpads.

‘I would be honoured, my lady. And, as it is such a pleasant day, perhaps you would care for a stroll along the main shopping streets?’ asks Porrett, in a seventh heaven. ‘I believe that Master Arthur has forgotten his hammer for extracting rock samples, so that could be purchased.’

‘I would be honoured, my lady. And, as it is such a pleasant day, perhaps you would care for a stroll along the main shopping streets?’ asks Porrett, in a seventh heaven. ‘I believe that Master Arthur has forgotten his hammer for extracting rock samples, so that could be purchased.’

and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of

and admire Wordsworth’s view in Walk 6, of

building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.

building. In the print looking down Fish Hill you can see the tower of St Magnus and the clock.