Duelling was very much a feature of the Georgian and early Regency period, the outcome of the code of honour that meant that a gentleman must defend his name and reputation (or that of a lady) against any slur or be branded a coward.

The rules were strict and a gentleman was supposed to know them and to possess a set of duelling pistols, just in case. It all seems very romantic and heroic with images of misty dawn meadows, the seconds standing by while the duellists, with stiff upper lips, casually make their preparations and discuss with their friends where to take breakfast later.

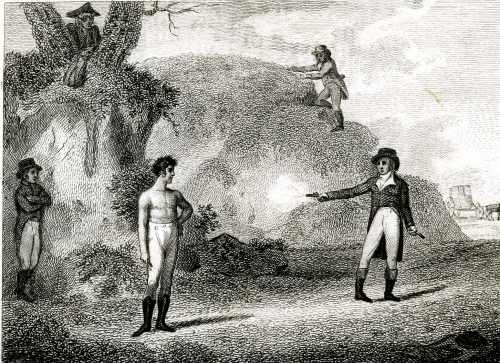

The print above, mysteriously captioned ‘Something Like It’, is from The Sporting Magazine, 1806 and shows a duellist displaying the correct degree of sang froid: having made his shot he stands waiting calmly for his opponent to take his. He has prudently removed all his upper clothing to prevent cloth being carried into any wound. The only information the magazine gives is that the meeting arose from, ‘a recent dispute in the sporting world…’

Even prominent politicians took part in duels. Canning (Foreign Secretary) versus Castlereagh (Secretary of War) in 1809, over Canning’s potting to have Castlereagh replaced, resulted in Canning being wounded in the thigh. In 1829 the Duke of Wellington met Lord Winchelsea following a dispute over the Catholic Emancipation Act. Winchelsea fired wide, Wellington shot a hole through his coat – whether deliberately or not is not recorded.

But duelling could have very serious consequences. Estimates of fatalities in England are about 15%, but they may very well have been higher, for the consequences of killing your man could be a trial for murder so duelling deaths may have been concealed as accidents. Even quite highly placed men found themselves taking an enforced holiday on the continent while their relatives exerted influence to allow them to return safely.

In Norfolk, on the B1149 near Aylsham, just south of its junction with the B1145, is what must be one of the National Trust’s tiniest sites, a little railed enclosure with an urn at the centre. This commemorates the last duel fought in Norfolk, a political affair. On 20th August 1698 Sir Henry Hobart MP of Blickling Hall, the leader of the Norfolk Whigs, met Oliver le Neve, a popular Norfolk Tory squire. Hobart had just lost his seat in the election of 1698 and accused le Neve of spreading rumours to the effect that Hobart was a coward and had behaved as such when he was Gentleman of the Horse for William III on campaign in Ireland. le Neve denied saying any such thing, making the counter-accusation that Hobart had fabricated it.

They met at what was then Cawston Heath, apparently without seconds, and fought with swords. le Neve was wounded in the arm but then stabbed Hobart in the stomach. Hobart died the next day at Blickling Hall. le Neve fled to Holland but became a Tory hero and the influence of his supporters allowed him to return to England in 1700, when he stood trial at Thetford Assizes and was acquitted. The memorial urn was erected by Sir Henry’s widow.

I had accepted duelling pretty much at face value and have even written duels into novels, but the true human cost of this highly sensitive sense of honour really came home to me while I was researching Driving Through Georgian Britain: the great coaching routes for the modern traveller. (Due out in July 2019). Tracing the route of the Great North Road, I explored the old churchyard of Sawtry St Andrews, Huntingdonshire.

The church had been pulled down in the Victorian period and the churchyard now is a patch of overgrown scrub and trees with gravestones leaning drunkenly at all angles.

I don’t know what made me clean the weeds away from one, a slate slab with the top broken off, but what I could read was:

[…] Leicester

[…] departed this Life

25th Day of June 1756

Aged 37 Years.

Near to this Stone Who’ere thou art draw near.

In Pity drop one pious friendly Tear;

Far from his Native Home, he lost His Life,

By One who seem’d his Friend; Ill timed strife.

The best of Husbands; to his Children dear

Courteous to all, and to his Friend Sincere.

Remorceless Fate, well may the Wretch feel woe,

While he in endless Bliss, and Pleasures flow.

I was so moved by this that I was determined to find the name of this man who, it seemed, was the victim of a duel between friends. The local Records Office supplied his name – James Ratford of Wotherington – and the confirmation that he was killed in a duel. So far I cannot find out anything more about the circumstances or about James himself – not helped by the fact that whoever made the entry in the burial register must have misheard the place name, because I can’t locate Wotherington anywhere. But the thought of that sorrowing widow and fatherless children and the wreck of his friend’s life has made me think twice about the romance of duelling!

The 19th century family would have worshipped under the gaze of the figure of Hope on the memorial to Mary Hare who died in November 1801. Hope is leaning on an anchor (her symbol) which also serves as a reminder that Mrs Hare’s father, Sir Francis Geary, Bart., was an Admiral of the White. The upside-down torch leaning against the urn is a symbol of a life snuffed out. Usually the length of the torch is an indication of the length of the life of the deceased.

The 19th century family would have worshipped under the gaze of the figure of Hope on the memorial to Mary Hare who died in November 1801. Hope is leaning on an anchor (her symbol) which also serves as a reminder that Mrs Hare’s father, Sir Francis Geary, Bart., was an Admiral of the White. The upside-down torch leaning against the urn is a symbol of a life snuffed out. Usually the length of the torch is an indication of the length of the life of the deceased.

There’s a very similar recipe in The Complete Confectioner (1815) by Fredrick Nutt with the note: N.B. These are very good for the stomach in cold weather.

There’s a very similar recipe in The Complete Confectioner (1815) by Fredrick Nutt with the note: N.B. These are very good for the stomach in cold weather.